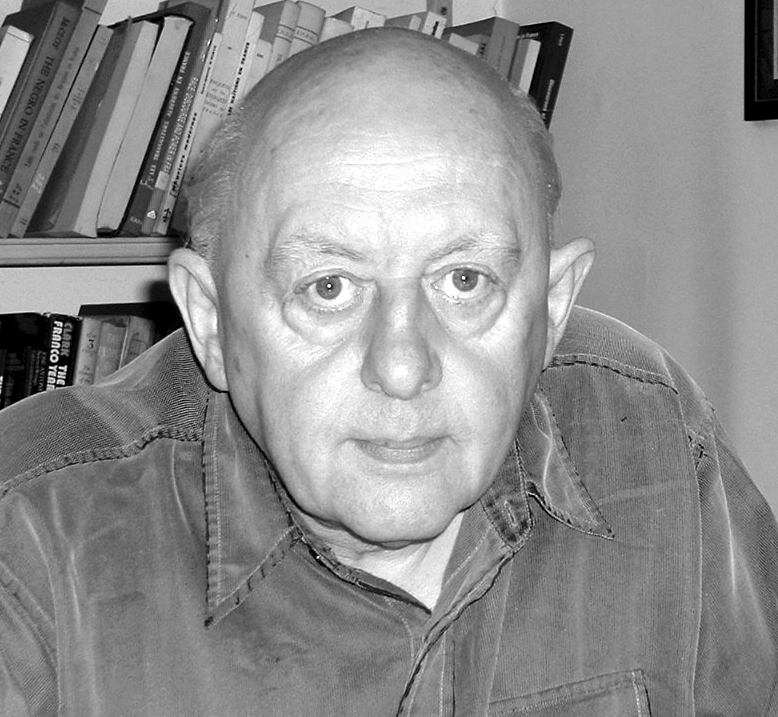

With the death of Ken Leech, on 12 September from a stroke, we have lost a pillar of the anti-fascist movement.

He was always there for the calling on in the struggle against racism – a thoughtful stalwart, a socialist who would stand up and be counted, unafraid of getting his hands dirty from community politics.

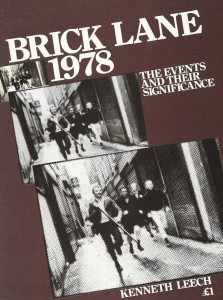

He was the most unlikely of Anglican clergymen. His calling had taken him to Soho and the homeless in the 1960s – where he set up the project Centrepoint, then to the youth drug scene – where he wrote Youthquake, and, then, in the 1970s, to the highly contested pastures of Bethnal Green. And it was there that he became known for his stand against the National Front and the extreme Right generally and for the Bengalis settled around Brick Lane.

He was the most unlikely of Anglican clergymen. His calling had taken him to Soho and the homeless in the 1960s – where he set up the project Centrepoint, then to the youth drug scene – where he wrote Youthquake, and, then, in the 1970s, to the highly contested pastures of Bethnal Green. And it was there that he became known for his stand against the National Front and the extreme Right generally and for the Bengalis settled around Brick Lane.

Even when he left the Church proper to become adviser to the British Council of Churches and later director of The Runnymede Trust he retained his strong commitment to anti-fascism, writing for the IRR on the New Right, Christian fundamentalism, racism and theology. Ken was a thinker and prolific writer. And it is salutary to remember today, when secularism is assumed to be the sine qua non of radicalism, that Ken represented a particular strand of radical prophetic Christianity, closest to Latin American liberation theology. Whilst he pamphleteered about Brick Lane and wrote In Doing Theology in Altab Ali Park, his impact on believers for Soul Friend, True Prayer, The Eye of the Storm, Spirituality and Pastoral Care should not be underestimated.

Ken, who was a guiding light of the Christian Socialist Movement, marched with CND and championed gender equality and justice for lesbian and gay clergy, of course never got any ‘preferment’ in the established Church. It is not there then that his legacy lies, but in the ‘subversive orthodoxy’ that he practised and preached.

I was most sad to hear about Ken Leech’s death. His book “Struggle in Babylon” (Sheldon Press, 1988) moved and inspired me profoundly.

In the Introduction, he wrote: “From an early age, I was conscious of the Church of England as a middle class presence within a mainly working class community… It was years later I came to see the degree to which the Church itself was a racist institution…”