A campaign is launched to demand justice following the death of Rooble Warsame in a local police station in Schweinfurt, Germany in February 2019.

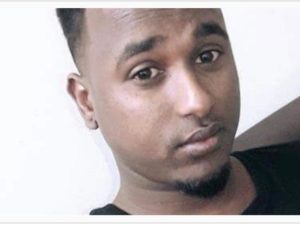

On the evening of 25 February 2019, 22-year-old Rooble Warsame was arrested and taken to a local police station in Schweinfurt, Germany. Within a few hours, he was declared dead.

Rooble was seeking asylum in Schweinfurt, Bavaria, living in bleak conditions at an Anchor centre, collective accommodation for asylum seekers and refugees.[1] Bavaria is a conservative region of Germany which has seen an increase in far-right and anti-immigrant sentiment in recent years. Before his death, Rooble experienced racism frequently as a young Black refugee from Somalia. Having learnt to speak German at an immigration detention centre in Austria, Rooble would always stand up for himself and wouldn’t hesitate to confront people who were racially targeting him.

Details are missing from the period of police custody, but a few hours later, police declared that Rooble had committed suicide in his cell. Suspicion has arisen due to the extreme unlikelihood of Rooble acting in this way after two hours in a police cell, but also at the police’s reluctance to cooperate with his grieving family, and the fact that the man Rooble was arrested with (possibly the only witness to Rooble’s death except the police officers themselves) has been missing for over a year. Police released him the day after, not considering him a witness to Rooble’s death, and failed to keep track of his whereabouts. The investigating agency (Staatsanwaltschaft) also failed — willingly or unwillingly — to record whether they investigated potential witnesses or not.

Initially, the police did not grant Rooble’s family access to see the cell where he died, and they were only permitted after persistent calls and demands. The Chief Officer claimed that Rooble used the cell bars to hang himself, but was unable to provide further explanation or evidence of the material that he would have used to do this. Rooble was given a relatively thick blanket, which police claim he tore to prepare a noose. However, the family says the bars were not strong enough to take the entire weight of a person. Rooble’s cousin Mohammad Yassin, who visited the cell, recalls: ‘The cell was two [by] four metres long. We searched everything. It is not possible to commit suicide in this space. Unless one continuously bangs one’s head against the wall, or strangles themselves with their own hands. There were no [things] in the room…no hook, no rope, no opening to attach anything to.’ These call to mind the circumstances around the death of Oury Jalloh in 2005 and Amad Ahmad in 2018, both in German police custody.[2] Authorities claim Jalloh set himself on fire, despite having his wrists and ankles chained to a bed in a holding cell, and Ahmad is alleged to have set his own cell on fire, despite a report commissioned by the ARD television program Monitor stating this as highly questionable.

Mohammad Yassin also recalls that the police did not expect Rooble to know his rights, or for anyone to file a complaint against them. They refused to cooperate until the family had legal assistance. The family say that the police were eager to cremate Roobles’ body as soon as possible, only prevented by the mosque community who insisted on giving Rooble an Islamic burial in the presence of family and friends. Those who saw Roobles’ body before he was washed by the Imam claim they saw horrific injuries, clearly indicating a struggle rather than a suicide. He was, they say, covered in fresh wounds, nail scratches, a knee injury, and no marks indicating self-strangulation.

Uniformed and non-uniformed police officers were present on the day of the burial, but the reason for this is unclear. Police surveillance of campaigners, a premature conclusion of investigations, systematic cover ups and the ruling of deaths as suicides despite clear indications to the contrary are frequent in such cases, as seen not only in the campaign for Oury Jalloh, Amad Ahmad and Adel. B, but also in the case of Yayya Jabbi, and many more. The Deaths in Custody Campaign has researched 159 cases of deaths in custody at the hands of the police, in state ‘care’ facilities, or due to negligence and misconduct in Germany between 1990 and 2020. Their research shows that Black people and people of colour are disproportionately at risk of death at the hands of the state.

Rooble’s family and friends are convinced that he did not commit suicide; he was in close and consistent contact with his family, and never expressed any suicidal ideation. The autopsy does not rule out murder, and officers have failed to provide evidence of how one would commit suicide in the way they claim Rooble did. Despite this, the public prosecutor’s department decided not to pursue charges against anyone involved, ruling his death as a suicide. The family’s lawyer has appealed, demanding the investigation be kept open, but this has been obstructed by the initial autopsy which states that suicide is a ‘possibility’.

The Justice For Rooble Campaign, led by his family, demands that:

- The truth behind Rooble Warsame’s death be exposed to the public and never forgotten;

- The missing witness be located, his accounts included in the investigations, and his safety and legal status protected;

- The case is kept open, and police officers involved in Rooble’s death stand a fair trial.

To support and stay up to date on the campaign, please follow @Justice4Rooble and @Justice4RoobleDE (for the German page) on Twitter. We will soon be launching a crowdfunding campaign for an independent autopsy into Rooble’s death, and a petition to put pressure on the Bavarian government to continue investigating the case and reveal the truth.