Francesca Humi, organiser and writer and former coordinator of the Crossborder Forum, asks what has changed in migration and border policies in Britain and France since the electoral change.

Britain and France: electoral change

This summer has brought about major electoral change in the UK and France. The Labour party unseated the Conservative government of 14 years. In France, following disastrous European parliamentary elections which saw a third of the vote go to Marine Le Pen’s far-right National Rally, president Emmanuel Macron called a snap legislative election, and in response, left-wing parties banded together to form the New Popular Front (NPF) to block as many National Rally candidates as possible. To the surprise of many, the NPF came first, although it failed to secure a majority, winning 180 seats in the National Assembly, while the president’s party came second, and the National Rally third with 143 seats. The lack of a clear parliamentary majority, combined with the Paris Olympics, led to months of political limbo as France waited for Macron to nominate a new prime minister who would then be tasked with forming a government. Finally, after months of consultations with various political figures, on 5 September, Macron named Michel Barnier, ex-Brexit negotiator for the European Union and right-wing government veteran, as prime minister. A shocking appointment, given that Barnier’s last government position had been a decade ago and that his party, the right-wing Republicans, won only 5.41% of the vote. The government that Barnier has subsequently put together is overwhelmingly right-wing: many of the new ministers, including Barnier himself, have anti-abortion, homophobic, and transphobic beliefs and voting records – foreshadowing a disastrous political climate for civil liberties, including migrants’ rights.

Tacking to the Right in France …

As prime minister, Michel Barnier has declared that he wants his government to combine firmness and dignity on migration, having described immigration into France as ‘often unbearable’ in a televised interview. In his speech to the Senate outlining the political priorities for his government, he pledged to speed up asylum decision times and to facilitate removals by working with countries of origin and transit and by allowing detention for longer periods. He also called for enhanced border security and the implementation of the new EU Pact on Migration and Asylum, a set of new rules managing migration and the common asylum system at the EU level, which was widely criticised by European civil society, and for additional support to Frontex, the European border enforcement agency.

Bruno Retailleau, the new interior minister (home secretary), has shared even harsher views on immigration since taking office, declaring that immigration is not a positive opportunity – for migrants or for France, and explaining that multiculturalism leads to the risk of France becoming a ‘multi-racist’ society. He is also pushing for more removals, gathering officials from the ‘ten departments with the most migration-related disorder to ask them to remove more, and regularise less.’ Retailleau is also proposing a return to ‘double punishment’ for migrants convicted of crimes (similar to Britain’s policy of mandatory deportation of foreign offenders sentenced to 12 months or more), meaning foreign offenders would be removed to their country of origin after serving their sentence. This proposal was warmly received by figures from the Right and far Right, including former president Nicolas Sarkozy, National Rally spokesperson Laurent Jacobelli, and far-right MEP Marion Maréchal, niece of Marine Le Pen. Other proposals from Retailleau include re-criminalising irregular stay and a referendum on migration, in line with Michel Barnier’s 2021 proposal to have a pause on migration for three to four years while France ‘gets a grip’ on its immigration policy.

… and in Britain

Across the Channel, the horizon is looking similarly bleak for migrants. Although the Rwanda Plan was scrapped shortly after Keir Starmer took office, the Labour government’s policies on immigration are otherwise similar to the Tories’, with the Labour manifesto pledging a new Border Security Command, bringing together the Border Force, the National Crime Agency, the Small Boats Operational Command created by Rishi Sunak, and intelligence and security officers. Home secretary Yvette Cooper announced a new Border Security, Asylum and Immigration Bill, to clear the asylum backlog and increase returns to ‘safe countries’, and to ‘crack down on criminal gangs’ by giving border officials further powers, ‘building on the success of robust powers to counter terrorism’, including powers such as border stops and searches, according to its briefing note. This dangerous piece of legislation would in effect bring counter-terror powers to immigration and border enforcement – further criminalising and ramping up surveillance of people on the move. The use of anti-terror powers in the public order context has already had a repressive impact on free speech and the right to public assembly, in particular for climate and pro-Palestine activists. This will have serious ramifications for Black, brown, and migrant people in the UK, who are already subject to increased surveillance and carceral punishment through policies like Prevent and citizenship deprivation.

Another core priority set out by the new Labour government is returns enforcement to replace the Rwanda Plan. This intention was clear even before Labour took power: as early as March 2024, Labour proposed a ‘Returns and Enforcement Unit’ to target refused asylum seekers, and in an election debate hosted by the Sun that went viral, Starmer described wanting to target communities with high numbers of undocumented migrants, such as, he said, Bangladeshis. Shortly after assuming office, Yvette Cooper announced a summer of immigration raids on nail bars and car washes to clamp down on ‘dodgy employers’ of undocumented migrants. The home secretary and prime minister also committed to working with European countries to address the ‘upstream causes of migration’, including through the Rome Process – a plan concocted by Italy’s Georgia Meloni to further increase the externalisation of European border enforcement.

France and Britain are on parallel political paths: both countries have seen their respective political centres shift further to the right as right-wing and far-right parties have successfully imposed their views in the public debate. Both countries are governed by a centrist party that positions itself as the last bulwark against the far Right, while both parties have essentially adopted right-wing positions on immigration. The UK especially so: many of the immigration policies of the past twenty years, which Labour seems intent on pursuing, are directly in line with those of the far Right: no recourse to public funds, mandatory deportations, reducing regularisation of undocumented migrants, cutting down on family reunion, and a ‘values’ component to achieve British citizenship. Many of these policies are identical to proposals from the National Rally and Eric Zémmour’s Reconquête, an even more extreme political party.

Enforcing the shared border

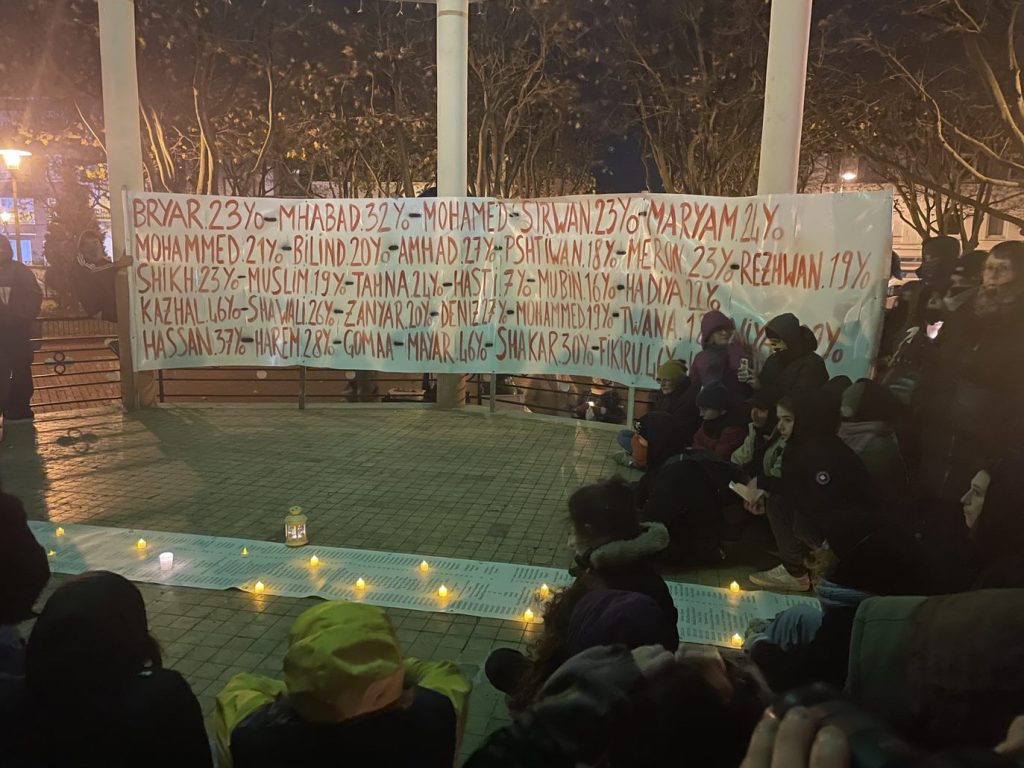

The two countries’ immigration policies are linked in more direct, tangible ways too. Since the 1980s, France and the UK have established a series of bilateral agreements setting out how migration is controlled and enforced between the two countries. These agreements represent a huge cost to the British government, which has spent nearly £1.1 billion since 1998 on enforcing the shared border.[i] However, this amount is likely to be much higher, as not all agreements and sums allocated to them are made public; they are often classified as confidential. There is also a devastating human cost to these agreements: since 1999, over 400 people on the move have died at the border – this includes people killed as they attempted to reach Britain in boats or lorries, victims of police brutality, and those who have died by suicide.

These agreements have put in place a system of increased militarisation, surveillance, and repression at the shared border through juxtaposed controls, allowing the border controls of each country to extend into the other, through the 1986 Treaty of Canterbury and the Sangatte Protocol of 1991.[ii] The 2003 Touquet Agreement introduced border controls in maritime ports of the Channel and the North Sea, whilst also banning people on the move from claiming asylum at the border. More recently, starting with the 2018 Sandhurst Treaty, a series of treaties and joint statements were agreed in close succession between 2018 and 2022 to tackle ‘illegal migration’. These agreements reinforced border infrastructure, surveillance and security tools, deploying more law enforcement across the northern French coast, and increasing cooperation between British and French border controls – representing about £193 million in spending by the British purse.[iii]

The details of how this massive amount of money is spent are unclear, but recent reporting shed some light: the majority is spent on transportation for border enforcement and police, including helicopters, cars, quad bikes, as well as surveillance equipment ranging from binoculars and drones to hunting cameras and endoscopes. Other purchases have included microwaves, vacuum cleaners, and car adapters for charging devices, the setting up of a horse brigade in the Somme and a contribution to French policing at the Franco-Italian border – further externalising the British border into Europe.

Despite all this expenditure, the agreements do not even achieve their stated aims: only about half of Channel crossings are intercepted[iv] and the increased militarisation of the border and restriction of safe routes has only increased the danger of crossings, rather than deterring them. As Parliament’s Foreign Affairs Select Committee found in 2019: ‘a policy that focuses exclusively on closing borders will drive migrants to take more dangerous routes, and push them into the hands of criminal groups’.[v]

What these agreements do achieve is a kind of legal paradox. The British border extends into France through juxtaposed controls and British taxpayers’ money funding French police and border enforcement, and by exporting the destitution, surveillance, and criminalisation characteristics of the British hostile environment policy into France. Migrants are already subject to British immigration policy once they reach northern France, yet they cannot claim asylum or make any applications to the Home Office from northern France.

Cross-border resistance

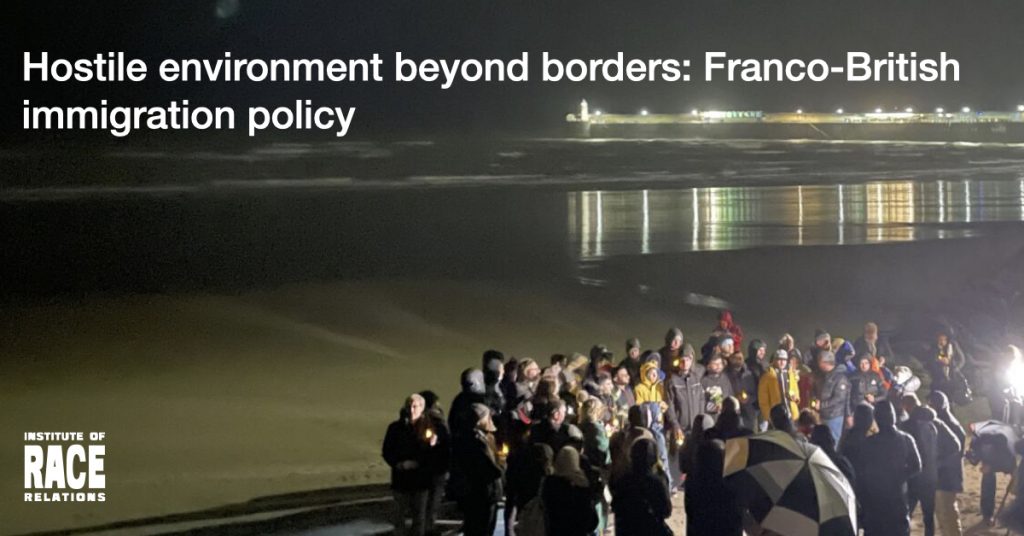

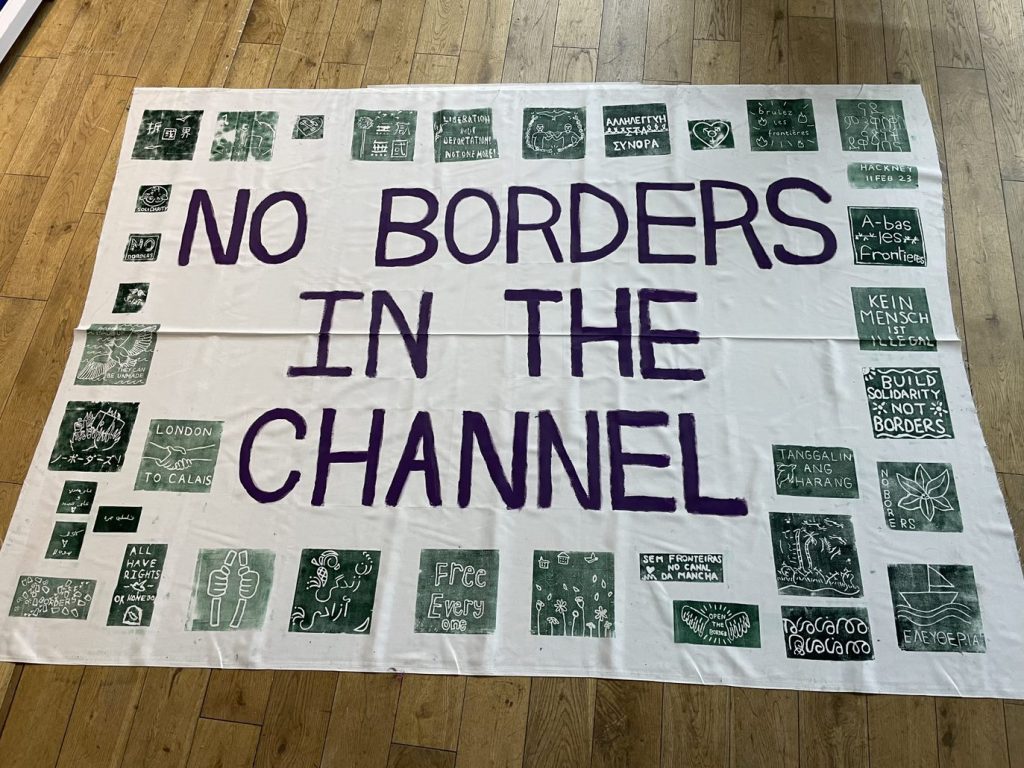

This extension of the border not only demonstrates how fluid borders are – and how attempts to enforce them are ultimately bound to fail – but also that we, as migrants, organisers, and abolitionists in Britain, France, and beyond have a duty to consider British and French immigration policy in direct conversation with each other. Because the hostile environment policy already exists in France, and because the violent treatment of people on the move in France is a direct driver of migration towards Britain,[vi] we must understand each country’s immigration policy as extensions of each other. This is something that is understood by civil society and grassroots organisations, which have increased mobilisation in response to the continued intensification of border enforcement. There is a long history of British people going to Calais and transit towns in northern France and Belgium to work or volunteer for organisations that support people on the move. But, recently, there have been more coordinated efforts to establish sustained organising and solidarity-building at the border. The Crossborder Forum is a network of Belgian, British, and French organisations and activists, which was set up in 2020 to ensure migrants’ rights organisations on either side of the border have access to reliable and regular information about policy and on-the-ground developments relevant to cross-border migration. This initiative plays a crucial role in building the infrastructure and systems necessary for long-term solidarity across borders, through regular meetings, translated materials, and resourcing opportunities for collaboration – similar to the role Migreurop plays at the European and North African level. The Plateforme des Soutiens aux Migrant-e-s and BelRefugees are doing similar work through their networks of local organisations and volunteer groups to ensure support provided across northern France and Belgium, respectively, is as coordinated and strategic as possible. Other initiatives include Captain Support, Watch The Channel, Refugee Legal Support, and Humans for Rights Network, who all work for migrant justice with an explicit transnational focus. Since 2022, France- and UK-based activists and NGOs have held joint ‘commemor-actions’ (commemorations with an action or mobilisation component) for the anniversary of the 24 November 2021 Channel disaster, during which at least 27 people died. The commemor-actions usually consist of a march through Dunkirk followed by a vigil for the 27 people who died and all those who have died at the border, with a vigil held at the same time in Folkestone. In both places, letters of relatives and survivors are read out to honour the memories of the dead.

Two sides of one racist coin

The complicity of the two countries’ authorities in border enforcement has implications beyond immigration policy. In 2022, French police killed 17-year-old Algerian-French boy Nahel Merzouk during a traffic stop, which led to mass mobilisation of Black and brown youth to protest police violence. In response to this, anti-riot police were sent out en masse to quell protests, which incidentally led to an exceptional two-week reprieve in police violence and surveillance for people on the move in northern France, as the police squads usually allocated to the northern coast were redeployed across the country. Three people subsequently died in the protests in the wake of Merzouk’s death, including one person who was hit by a rubber bullet fired by French police. The police force that kills migrants at the border, funded by Britain, is the same force that kills Black and brown youth across France.

It is also important to note that recent waves of anti-migrant hate speech and violence in both France and Britain have been triggered by incidents of violence against women and girls perpetrated by men. This summer’s anti-migrant riots across Britain were launched at the behest of Tommy Robinson and other far-right leaders in response to a misogynistic attack on a Taylor Swift dance class in Southport, which killed three young girls. In September, a female student was killed in Paris by a Moroccan man who had received a removal order. Despite another current case of gendered violence in France, involving a woman allegedly drugged by her husband and raped by over 80 men for decades, it is the former case that has been seized on, used as a rallying call by the far Right, supported by Bruno Retailleau, to increase removals and cut immigration. This exploitation of violence against women is characteristic of the far Right’s tactic to whip up racism and xenophobia, distracting attention from the root causes of gendered violence.

Britain and France offer useful mirrors to each other to help us understand how liberalism paves the way to fascism. In France, the self-labelled centrist Macron, who won the presidential elections twice to block Marine Le Pen, directly invited members of the (far) Right to form a government despite a third of the French electorate voting for the left-wing coalition. In Britain, Starmer’s Labour has largely unquestioningly adopted Conservative immigration policy and Reform-adjacent positions – in some cases going even further, as with this summer’s raid blitz. The past 30 years of bilateral agreements emphasise how intertwined and externalised domestic immigration policy actually is, whilst the Right pushes for nationalist isolation in the name of ‘stopping the boats’. Finally, the weaponisation of migration and gendered violence remind us of how integral gendered and racial constructions of the nation are to Western nation-states. White citizen men perpetrating gendered violence represent no-one but themselves; migrant, Black, brown, or Muslim perpetrators are seen as representatives of all. The parallel political developments of France and Britain are an urgent reminder of the importance to continue building solidarity across borders and causes in order to tackle fascism at its root.

[i] Pierre Bonnevalle, 30 years of creating the deterrence policy, p. 251, Plateforme des Soutiens aux Migrant-e-s, English translation: Crossborder Forum, 2023.

[ii] 30 years of creating the deterrence policy, p. 36.

[iii] Melanie Gower, Irregular migration: A timeline of UK–French cooperation, Research Briefing No 9681, House of Commons Library, 22 March 2023, p. 2.

[v] Responding to irregular migration: finding a diplomatic route, HC 107, 4 November 2019.

[vi] Marta Lotto, On the border – life in transit at the French-British border (2021), p. 55, Plateforme des Soutiens aux Migrant-e-s, English translation: Crossborder Forum, 2023.