The unique contribution of teacher Chris Searle to education in London’s East End was celebrated at the launch of his autobiography, Isaac and I: a life in poetry, on 20 May.

There is some archive footage of Chris Searle, long-haired in corduroy jacket walking head, shoulders and torso above a sea of milling children, trying to tell them something. As we watched at a packed meeting in Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives in Stepney Green on 20 May, someone exclaimed ‘Jesus Christ!’ and I, too, couldn’t help recalling those stylised paintings of Jesus on the Sunday School walls. But Chris was not asking them to become fishers of men, he was, actually asking the pupils at Sir John Cass School – who, in a momentous show of solidarity had come out on strike because Mr Searle, ‘Sir’, their favourite English teacher, had been sacked for publishing a book of their poems, Stepney Words – to get out of the pouring rain.

There is some archive footage of Chris Searle, long-haired in corduroy jacket walking head, shoulders and torso above a sea of milling children, trying to tell them something. As we watched at a packed meeting in Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives in Stepney Green on 20 May, someone exclaimed ‘Jesus Christ!’ and I, too, couldn’t help recalling those stylised paintings of Jesus on the Sunday School walls. But Chris was not asking them to become fishers of men, he was, actually asking the pupils at Sir John Cass School – who, in a momentous show of solidarity had come out on strike because Mr Searle, ‘Sir’, their favourite English teacher, had been sacked for publishing a book of their poems, Stepney Words – to get out of the pouring rain.

And some forty-six years later, many of these same pupils, still living in London’s East End, gathered, at the launch of Chris Searle’s autobiography, Isaac and I: a life in poetry, to pay homage to the one teacher who had not written them off as academic failures, who had taken the trouble to open their eyes to the beauty and humanity of the East End and nurture their ability to express their feelings through poetry. Few teachers can have had the impact on a community that Chris has had. And there was something so evocative to hear a well-built worker from Billingsgate Fish Market recall (in market language) that because of his Jewish roots he was kept from the good Anglican school and sent to Langdon Park instead. There he became a hardened truant till, that is, Mr Searle moved there in 1974, when learning for him caught fire. Chris’s influence through poetry was not restricted to the formal classroom. He went on to form a community poetry group – the Basement − open to all, which published numerous small collections and continued for over nineteen years. And here they were, some in person, some on film and slide, some in (bawdy) song, recalling the importance of Chris and the land of poetry, where they discovered themselves.

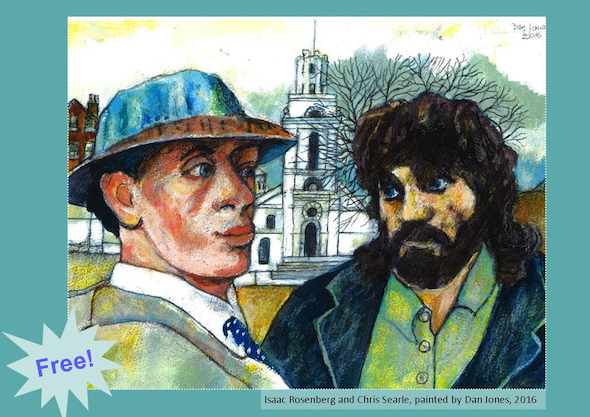

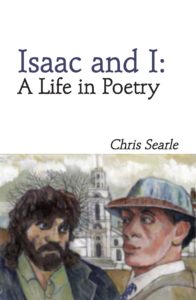

It was an amazingly warm and uplifting afternoon – if an odd book launch. For, humble as ever, Chris obviously wanted to share the event. And he kept his contribution very short – recalling the indelible influence on him of East End, working-class, ‘war poet’ Isaac Rosenberg and his amazement, almost bemusement, at the strength (and professionalism) of that 1971 school strike.

But there is so much that is telling in the new publication. On the one hand, Chris’s own early story from birth in Essex in 1944, his educational experience (including failing the eleven plus exam), his travels in Canada, the US and the Caribbean as a student in the 1960s, where he was open to everything and everyone and the happenings − such as the killing of Martin Luther King, anti-Vietnam protests, the Black Panthers − which changed his life, are fascinating and sum up the ‘60s very well. On the other hand, the school strike over his sacking for producing Stepney Words was momentous and deserves its place in working-class history. And here it is enunciated over three chapters of this 290-page paperback.

Staid, traditional, Anglican, Sir John Cass and Redcoat School was obviously not the ideal place for this radical, idealistic, educationally brave young English teacher keen to engage the school’s working-class pupils in ‘the creative-critical principle’ through poetry. When the school refused the idea of publishing the pupils’ true, raw poems about what they felt of their surroundings, Chris, with photographer Ron McCormick and community support, published them in a simple small pamphlet, Stepney Words. It was predictable perhaps that the governors, given their history, would cavil at his ‘defiance’. Less predictable though was the school students’ response to his suspension − strikes, protests, including those from other schools in the area, and an 800-strong march to Trafalgar Square. For they too had their history – in the militant trade unionism of their families in the docks and markets of the area. Surprisingly to us now, the mass media reported very sympathetically on the imaginative venture of probationary teacher Chris Searle and the book of poetry, and the school students’ defence of its instigator, became a national cause celebre, with support from Jack Dash and the unions, the Bishop of Stepney, educationalists like A. S Neill, playwrights like Arnold Wesker. Stepney Words had to be reprinted and reprinted, poems were broadcast on TV and read at the Institute of Contemporary Arts. A second book of poetry was published as Stepney Words 2. Chris Searle was eventually reinstated at the school in 1973.

The launch of Isaac and I could have been an elegiac affair harking back to a (white) working-class culture that once was. But it was nothing of the sort, because of Stepney Words III. The Rich Mix Centre with Apples and Snakes and community poets including Chris, had been running workshops in four local East End secondary schools to develop a collection of poetry reflecting today’s reality. And to end the afternoon we heard from three of the published young poets, using the same humanitarian but critical eye on their surroundings. The names might have changed from Isaac or Tony – now they were Ayaan, Ibrahim, Mariahm, Chioma, Duaa − but this was the new generation of writers and fighters for London’s East End.

The launch of Isaac and I could have been an elegiac affair harking back to a (white) working-class culture that once was. But it was nothing of the sort, because of Stepney Words III. The Rich Mix Centre with Apples and Snakes and community poets including Chris, had been running workshops in four local East End secondary schools to develop a collection of poetry reflecting today’s reality. And to end the afternoon we heard from three of the published young poets, using the same humanitarian but critical eye on their surroundings. The names might have changed from Isaac or Tony – now they were Ayaan, Ibrahim, Mariahm, Chioma, Duaa − but this was the new generation of writers and fighters for London’s East End.

Isaac and I: a life in poetry is available £10 post free (UK only) to IRR supporters, from the publisher Five Leaves (call Five Leaves on 0115 837 3097 or email: bookshop@fiveleaves.co.uk).

Related links

Buy Stepney Words III here