Below we reproduce an excerpt from the introduction to the January issue of Race & Class, a special issue on ‘Reparative histories’.

The ‘balcony scene’ during which the out-of-time drugs baron, Avon Barksdale, and his modernising partner, Stringer Bell, reminisce about their errant childhoods is often hailed as one of the most compelling dramatic moments in The Wire.[1] Suffused in tragic foreboding of Shakespearian proportions, the two men, back-lit by the twinkling lights of Baltimore’s World Trade Center, corporate skyscrapers, luxury hotels and bobbing gin-palaces, reflect on how good it feels to be looking at ‘the view’ from their own piece of million-dollar waterfront real estate. Barksdale recalls – nostalgically – that the two had once owned the harbour-front with nothing but their bodies and their spirits, by out-running security guards everyday for sport. Conceding to Bell’s observation that their persecution had been the appropriate response from the police given that they were robbing stores, Barksdale nonetheless prompts him to remember the meaningfulness, and the pointlessness, of their actions. With wry humour, he reminds Bell of the day he lifted a badminton racket and a net even though they had no yard in which to play the game. The moment registers the contradictory meanings of property and ownership and the ways in which, in their various forms, they are bound into the bloody sinews of ‘race’ violence, poverty, addiction, corruption, lucre and speculative greed that constitute American capitalism.

The ‘balcony scene’ during which the out-of-time drugs baron, Avon Barksdale, and his modernising partner, Stringer Bell, reminisce about their errant childhoods is often hailed as one of the most compelling dramatic moments in The Wire.[1] Suffused in tragic foreboding of Shakespearian proportions, the two men, back-lit by the twinkling lights of Baltimore’s World Trade Center, corporate skyscrapers, luxury hotels and bobbing gin-palaces, reflect on how good it feels to be looking at ‘the view’ from their own piece of million-dollar waterfront real estate. Barksdale recalls – nostalgically – that the two had once owned the harbour-front with nothing but their bodies and their spirits, by out-running security guards everyday for sport. Conceding to Bell’s observation that their persecution had been the appropriate response from the police given that they were robbing stores, Barksdale nonetheless prompts him to remember the meaningfulness, and the pointlessness, of their actions. With wry humour, he reminds Bell of the day he lifted a badminton racket and a net even though they had no yard in which to play the game. The moment registers the contradictory meanings of property and ownership and the ways in which, in their various forms, they are bound into the bloody sinews of ‘race’ violence, poverty, addiction, corruption, lucre and speculative greed that constitute American capitalism.

All the while, the exchange remains framed by the just out-of-focus glitter of Baltimore’s thrusting urban redevelopment. The harbour-side lights project far beyond the narrative arc of the intimate drama to confirm – dully but literally – the place of history, and the place of the history of ‘race’, in cementing the tragically inassimilable lineaments of the dramatic moment. The two men do not need to say it but they both know in their bones that, long before it became the inaugural site of their own awakening to their dispossession, and then the poisoned site of their temporary overcoming, Baltimore’s harbour was once the epicentre of America’s domestic slave trade. the coordinated business of racialised, and nationalised, human trafficking that boomed in the wake of the legal abolition of the transatlantic slave trade, and which, through its intricate historical legacies, had helped to shape their fate, was anchored precisely here.

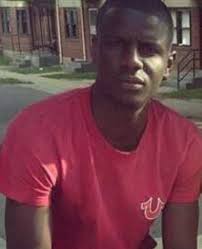

The imperative to acknowledge that embodied, yet also thoroughly historical, legacy has only intensified as Baltimore reels – at the time of writing this introduction – from the police killing of Freddie Gray, and the rioting that has followed, but most commentaries have wilfully ignored making direct connections between America’s slaving past and its present in this context. As an easier – perhaps – alternative, allusions to The Wire have peppered recent reflections and media reactions to what has unfolded. The drama did capture aspects of the complex interconnections between corruption, power, structural racism, economic exploitation and the inevitable failures of liberally-oriented progressive policy even to ameliorate the problems of urban Baltimore, and it was extraordinary that it did so. Ultimately, The Wire’s narrative thrust was elegiac and redemptive, however, insofar as it confirmed that living beyond the law cannot be a viable alternative to trying valiantly to make one’s way against the tide of racism and inequality. In the end, bourgeois moral values trumped the representation of politicised resistance. Neither did The Wire risk imagining what such resistance might achieve. Instead, rebellion was registered as a ruthless, and fatal, criminality that entranced and horrified in equal measure. The Wire did not engage directly with the history, solidarity and dialectics of political protest, violent or otherwise; its force was always both constrained and enabled by its commitment to the reforming zeal of social realism. This is why the melancholy of The Wire has been able to offer a generalised and acceptable representational frame or genre for thinking about the ‘real’ events of Freddie Gray’s murder and the reaction to it, but the moments where the drama did speak directly, and critically, to them were glossed. Even David Simon, the drama’s writer and producer, in a revealing initial knee-jerk reaction, chose to eschew activating the energies of his own art in favour of dismissing the rioters as senseless and criminal, and by appealing to them to just ‘go home’.[2]

The imperative to acknowledge that embodied, yet also thoroughly historical, legacy has only intensified as Baltimore reels – at the time of writing this introduction – from the police killing of Freddie Gray, and the rioting that has followed, but most commentaries have wilfully ignored making direct connections between America’s slaving past and its present in this context. As an easier – perhaps – alternative, allusions to The Wire have peppered recent reflections and media reactions to what has unfolded. The drama did capture aspects of the complex interconnections between corruption, power, structural racism, economic exploitation and the inevitable failures of liberally-oriented progressive policy even to ameliorate the problems of urban Baltimore, and it was extraordinary that it did so. Ultimately, The Wire’s narrative thrust was elegiac and redemptive, however, insofar as it confirmed that living beyond the law cannot be a viable alternative to trying valiantly to make one’s way against the tide of racism and inequality. In the end, bourgeois moral values trumped the representation of politicised resistance. Neither did The Wire risk imagining what such resistance might achieve. Instead, rebellion was registered as a ruthless, and fatal, criminality that entranced and horrified in equal measure. The Wire did not engage directly with the history, solidarity and dialectics of political protest, violent or otherwise; its force was always both constrained and enabled by its commitment to the reforming zeal of social realism. This is why the melancholy of The Wire has been able to offer a generalised and acceptable representational frame or genre for thinking about the ‘real’ events of Freddie Gray’s murder and the reaction to it, but the moments where the drama did speak directly, and critically, to them were glossed. Even David Simon, the drama’s writer and producer, in a revealing initial knee-jerk reaction, chose to eschew activating the energies of his own art in favour of dismissing the rioters as senseless and criminal, and by appealing to them to just ‘go home’.[2]

But Simon’s efforts cannot close down the interpretive possibilities of his drama. The location for the three-minute balcony scene provided the narrative fulcrum between the first three and the last two series of The Wire by registering the fact that Baltimore’s postmodern harbour-front – exemplar of acquisitive aspiration – squats atop the historical geography of US slavery. The dramatic moment confirms the power of cultural production to speak to current socio- economic conditions, and it opens up a route into thinking about what a perspective shaped by the concept of ‘reparative history’ might mean or might suggest. This special issue of Race & Class is concerned with just this question, and how we can unpack those complex interconnections between past and present in the context of contemporary resistances to racism and the legacies of colonialism. In relation to slavery, if the call for reparations forces the contemporary world to face its slaving past, what does this do to the historical narratives which have structured those pasts? Moreover, for our purposes, how does ‘the reparative’ reframe those narratives, to make them speak? How, if at all, does it disrupt liberal narrative structures which seek to domesticate and cauterise the radical histories of resistance to white supremacy?

History as agency

To return to Baltimore, there is a history here that can be reclaimed and occupied. In a blistering article in the wake of the riots, Peter Linebaugh reminded readers of the power that a historical perspective on the present carries. Baltimore was the ‘capital of the domestic slave trade’ but this is only half the story.[3] He notes the ‘ill-wind’ of resistance, too, by referencing Baltimore’s place in Frederick Douglass’ escape route from slavery. Irish dockers aided Douglass by finding him employment at Fell’s point. This is the outlying part of Baltimore’s harbour where slave traders preferred to board their captives out of the way of judgemental on-lookers, and because obstructive African American stevedores were rendering the nation’s borders porous in more ways than one. Particularly significant for the purposes of this introduction, Linebaugh also remembers a perhaps less acknowledged story about Benjamin Lundy, the radical Quaker abolitionist, who, while based in Baltimore, dared to argue for unconditional emancipation for the first time. Lundy was a key influence on Garrison, and this influence was to ignite a further wave of abolitionist resistance, but he was not just a man of radical ideas. He also stood up physically to the violence of the slaveholders.

Linebaugh notes Lundy’s violent confrontation with Austin Woolfolk, Baltimore’s most notoriously successful slave trader.[4] Woolfolk was outraged at Lundy’s slandering of him in his abolitionist magazine, The Genius of Universal Emancipation, and accosted him one day with fists and blows. Lundy pressed assault charges only to face humiliation from the ruling class. The judge fined the slave trader one dollar, and gave a speech about the slave trade’s economic benefits to Maryland, not to mention the ways in which it helped to remove a ‘great many rogues and vagabonds who were a nuisance to the state’.[5]

Linebaugh’s timely reminder of this moment, a moment which registers originary racial oppression and resistance in solidarity, has more significance still if we excavate further that resistance. Woolfolk’s attack on Lundy was motivated by the latter’s exposure of his treatment of one of his enslaved captives.[6] Woolfolk had shipped William Bowser, already confined in the pens as a runaway, on his slaver the Decatur, bound for New Orleans in 1826. But Bowser, along with others, conspired to rise up and take the ship, and to sail for Haiti – and freedom.[7] They nearly succeeded. The mutiny was successful but freedom was cut short when the Decatur was accosted by two American ships while the rebels were attempting to work out how to navigate. Finally, forced back into New York, Bowser and his fellow mutineers ran again. He was caught – the only member of the Decatur’s cargo to be captured – and brought to trial for the murder of the ship’s Captain and Mate. Woolfolk was so incensed by Bowser’s refusal to submit to his authority – despite his eventual capture – that he assaulted Lundy for slandering him and for publicising the mutiny. He later turned up at Bowser’s hanging to berate, pathetically, the man that he regarded simply as his property, only to be pushed out by the mob.

William Bowser has not taken his place amongst the canon of great resisters of slavery such as Nat Turner, Denmark Vesey or Madison Washington, whose own mutiny on the Creole in 1841 was outstandingly successful, but his story registers the countless acts of rebellion that can be retrieved from the archive. That archive is indeed impoverished, partial and bequeathed from ‘above’, and the scandal of its scant leavings needs to be acknowledged. One does not have to struggle too hard to read against its grain to find a myriad of stories like Bowser’s – as many historians have already shown. One just has to choose to look, or rather to look for those resistant moments which puncture the silence of the racially oppressed in the ledgers, insurance documents, commissions, newspapers and testimonies which form the grim chronicle of the colonial records.

Mourning and memory: narrating history

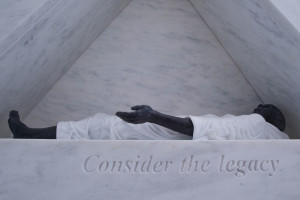

Three weeks before Freddie Gray was murdered, but amidst the media’s focus on the everydayness of black killings by the police, a permanent monument commemorating the victims of the slave trades and slavery was unveiled, not far away, outside the United Nations building in New York.[8] The event signalled the fact that slavery is finally being officially commemorated amidst the largely conservative and ahistorical analysis of the relation between ‘race’ and injustice in contemporary Euro-America. Unsurprisingly, there is no room for rage, resistance or politics in this auspiciously sited memorial. The monument makes no reference to Turner, Vesey or Douglass, let alone Bowser. Entitled ‘Ark of Return’ (to where?) the starkly white, disjunctive but pointed linear lines of the modernist-inspired structure construct a coercive narrative trajectory for the visitor that does not aid her historical or geographical orientation. Perhaps this is intentional. Momentary confusion in the face of the sublime gives way, however, to its accommodation.

In recognition of the global scale of transatlantic slave trading, a carved map of the Atlantic commands the visitor to focus and to ‘Acknowledge the tragedy’. As they move on, visitors encounter a classical sculpture of a disempowered African (black) man, clad in (white) biblical robes, lying prone in an oppressive small alcove. Below his body are the words, ‘Consider the legacy’. Signifying the untold suffering of the Middle passage, its ‘legacy’ is left for the visitor to imagine. The final injunction, ‘Lest we Forget’, renders it difficult to understand what needs to be remembered and what needs to be forgotten except for a diffused notion of suffering and victimhood that has somehow been borne with fortitude and resilience. While long overdue, the monument casts history within a choreographed narrative of mourning but leaves the visitor to work out what it means. It is both a packaging of memory, and a challenge to work out the shape of that memory – although its very form has circumscribed that shape in myriad ways.

The ‘Ark of Return’ is not singular in its memory narrative. The horrors of Euro-American labour extraction from slavery, to the high imperial moment, to the contemporary demands of globalisation are mostly made publicly visible through a mournful aesthetic of trauma, where both the event being marked and the spectators who bear witness to this event are isolated from the wider totalising narratives of both capitalist exploitation and resistances to it. Sublimity and awe may, indeed, be appropriate responses to the West’s colonial crimes but they also, potentially, rip those crimes from their history and freeze them as examples of excessive brutality whose relationship to the liberal state is antagonistic, rather than constitutive. Our concept of ‘reparative history’ is thus one that recognises the legitimacy of trauma in response to the dark history of modernity, but which also foresees the limitations of trauma as the rarefied space which neoliberal hegemony not only accommodates but positively demands as a response. Once again, the black body comes to signify a spectoral site of shame, only here not in the service of abolitionist fervour but of sublime affect, quarantined from the present, ‘experienced’ but rendered without continuity to contemporary racialised labour practices and contemporary racist violence.

The ‘Ark of Return’ is not singular in its memory narrative. The horrors of Euro-American labour extraction from slavery, to the high imperial moment, to the contemporary demands of globalisation are mostly made publicly visible through a mournful aesthetic of trauma, where both the event being marked and the spectators who bear witness to this event are isolated from the wider totalising narratives of both capitalist exploitation and resistances to it. Sublimity and awe may, indeed, be appropriate responses to the West’s colonial crimes but they also, potentially, rip those crimes from their history and freeze them as examples of excessive brutality whose relationship to the liberal state is antagonistic, rather than constitutive. Our concept of ‘reparative history’ is thus one that recognises the legitimacy of trauma in response to the dark history of modernity, but which also foresees the limitations of trauma as the rarefied space which neoliberal hegemony not only accommodates but positively demands as a response. Once again, the black body comes to signify a spectoral site of shame, only here not in the service of abolitionist fervour but of sublime affect, quarantined from the present, ‘experienced’ but rendered without continuity to contemporary racialised labour practices and contemporary racist violence.

Back in 2011, a message was read from the UN Secretary General at the launch of the memorial project that would become the ‘Ark of Return’. Ban Ki-moon’s message made a set of concrete historical connections that would not be clearly conveyed in the final monument itself. Ban Ki-moon stated that the memorial would acknowledge the ‘crimes and atrocities committed over the course of four centuries’, ‘remind the world of those slaves, abolitionists and unsung heroes who managed to rise up’ and ‘serve as a call to action against contemporary manifestations of slavery’. He noted the historical transformation of slavery into other forms of coerced labour – ‘serfdom, debt bondage and forced and bonded labour; trafficking in women and children, domestic slavery and forced prostitution, including of children; sexual slavery, forced marriage and the sale of wives; child labour and child servitude’ – that continue into the present.[9] Ban’s acknowledgement of multiple forms of exploitation speaks to a connected if complicated history which, despite his sweeping assortment of coercive practices, is relevant in the context of the dominant narratives of traumatic memorialisation.

It has frequently been noted that slavery and the slave trade are now being fairly routinely publicly commemorated in Europe and the US. Yet, as Joel Quirk notes, what is striking about the sombre acknowledgements from political elites is the ways in which they mourn, ‘regret’, or remember slaving’s past as tragedy while quickly shifting the focus from the claims of this history to the supposedly more pressing problems of the present moment.[10] A case in point is Tony Blair’s infamous speech, on the bicentenary of the British abolition of the slave trade in 2006, in which he resolutely refused to apologise for slavery, and focused instead on what he described, far more vacuously than Ban Ki-moon, as ‘the problems of Africa and the challenges facing the African and Caribbean diaspora today’. Blair went on repeatedly to highlight the need to ‘acknowledge the unspeakable cruelty that persists in the form of modern day slavery’ as a way of moving on quickly from the past.[11] It was widely recognised at the time that Blair’s carefully scripted evasion of any apology was in response to the pressure of the reparations campaign. Any direct admission of culpability in slaving by the British state risked enhancing the threat of a possible legal claim.

As Quirk notes, elite hand-wringing about contemporary human trafficking has come to serve not as a way of forging historical connections but for actively preventing them from being made. This evasion is in no small part due to the political pressure of the reparations campaign which places a particular purchase on history, and on the history of ‘race’. The very existence of the campaign challenges the progressive onward march of freedom from below by demanding the recognition and repair of centuries of exploitation, expropriation and violence not just by building monuments or by demanding financial payback. We argue that it also demands, and is engaged in, active exploration of the continuities between Euro-American racism, modern liberal democracy and neocolonialism in relation to a legacy of imperialism and the slave trade. That wider project is not only addressing the kinds of damaged histories that slave descendants inherit and through which they continue to live. It also involves engaging with the issue in its full geopolitical global context. It includes, therefore, exposing the ways in which slavery and the slave trade contributed to the modern industrial complex. Activists are not simply naming key culprits, they are also naming the structures of governance at corporate, national and global level.

To remember slavery by uncritically picking up the mantle of elite white abolitionism in the name of stamping out contemporary human trafficking thus functions as a way of avoiding direct confrontation with the legacies of slavery and empire since it would involve facing a history that challenges the very foundations of Euro-American supremacy.

Perhaps then it is unsurprising that Ban Ki-moon’s speech, which had the potential momentarily to activate politically a memory of the past – as one bequeathing legacies of injustice but also of struggle – for understanding the present, was ultimately punctured by his closing remark. Acknowledging contemporary ‘reality’ as a product of the past, he concluded, ‘obliges the international community to bring perpetrators to justice and to continue pursuing with vigour its efforts to uphold human rights and human dignity’. That was in 2011. The current EU response to the mass drownings of African and Middle Eastern refugees in the Mediterranean is perhaps a sufficient comment on this statement.

Repair, rescue, rage

Thinking the present conjunction of fury on the streets of Baltimore, the melancholy trauma enshrined in the UN monument, the reactivation of the reparations campaign by CARICOM, and the mass drownings of African and Middle Eastern refugees in the Mediterranean magnifies the potency of history, and the ways in which the histories of slavery and colonialism continue to be mobilised.

As the number of refugees drowning in the Mediterranean rose sharply in the summer of 2015, the direct result of the purposeful reduction of maritime rescue resources, analogies began to be made with the transatlantic slave trade. The abolitionist iconography of Middle passage horror seemed almost too obvious a referent in its ability to convey the barbarity that was unfolding on the margins of Europe. A frustrated Italian Prime Minister, Matteo Renzi, named the events directly as akin to the transatlantic slave trade.[12] The unfolding disaster ‘pricked the conscience’ of EU leaders who had, until it became untenable, been so intent on securing their borders that the argument around ‘humanitarian rescue’ had been transformed from the need to recognise human life and dignity to one about so-called ‘push and pull’ factors. ‘Migrants’ continued to drown as a military approach designed to quash an ugly symptom of global labour exploitation foundered amongst associated questions of how to bring the perpetrators of human trafficking to justice, and what exactly should be done with those who manage to be rescued. The rescued have been quickly incorporated into an invidious racialised discourse of ‘us’ and ‘them’ to emerge as a threatening and dehumanised ‘swarm’ surrounding Europe.[13] That discourse remained intact even in the context of the heartening if complex responses of the populations of Europe to the photograph of the drowned Syrian child Alan Al-Kurdi. The concept of the ‘refugee’ as ‘human’, and thus worthy of sympathy, especially in relation to women and children, left undisturbed the concept of ‘migrant’ as the threatening male ‘other’.

As the number of refugees drowning in the Mediterranean rose sharply in the summer of 2015, the direct result of the purposeful reduction of maritime rescue resources, analogies began to be made with the transatlantic slave trade. The abolitionist iconography of Middle passage horror seemed almost too obvious a referent in its ability to convey the barbarity that was unfolding on the margins of Europe. A frustrated Italian Prime Minister, Matteo Renzi, named the events directly as akin to the transatlantic slave trade.[12] The unfolding disaster ‘pricked the conscience’ of EU leaders who had, until it became untenable, been so intent on securing their borders that the argument around ‘humanitarian rescue’ had been transformed from the need to recognise human life and dignity to one about so-called ‘push and pull’ factors. ‘Migrants’ continued to drown as a military approach designed to quash an ugly symptom of global labour exploitation foundered amongst associated questions of how to bring the perpetrators of human trafficking to justice, and what exactly should be done with those who manage to be rescued. The rescued have been quickly incorporated into an invidious racialised discourse of ‘us’ and ‘them’ to emerge as a threatening and dehumanised ‘swarm’ surrounding Europe.[13] That discourse remained intact even in the context of the heartening if complex responses of the populations of Europe to the photograph of the drowned Syrian child Alan Al-Kurdi. The concept of the ‘refugee’ as ‘human’, and thus worthy of sympathy, especially in relation to women and children, left undisturbed the concept of ‘migrant’ as the threatening male ‘other’.

What is happening in the Mediterranean is clearly not a contemporary equivalent to the transatlantic slave trade. The rhetoric shows that the analogy is politically and ideologically powerful nevertheless. As critics have noted, it initially raked up, however belatedly, a sense of ‘abolitionist’ outrage – freighted with redemptive historical precedent – to justify military aggression as the humanitarian ‘solution’ to a contemporary problem of Euro-America’s own making.[14]

Understandably, many have been horrified by the glib use of the Middle passage in the service of either eliding any responsibility to provide sanctuary for these refugees or using the language of ‘trafficking’ to suggest a criminal rather than a geopolitical source of the turmoil in the Middle East. Suffice to say, in this context, that any links we may draw between these events and the history of slavery are fully cognisant of the abuse of history being employed by the gatekeepers of fortress Europe. In the case of Europe’s leaders, drawing these connections misrepresents and distorts both history and the contemporary moment.

A reparative history, however, is not one that would shy away from making the connection between historic slave trading and contemporary human trafficking and human smuggling because of the potential for its ideological appropriation or, indeed, because focusing on one moment risks deflecting attention from the other. Both arguments risk throwing the baby out with the political bathwater by ignoring the wider historical context of both moments: imperialism. It would note that what is being remembered and mobilised by political elites, and what is shaping the ground of the debate, is not even the history of slaving, or, if it is, it is that history as it is structured by the progressive triumphalism of white abolitionism. The stated intent of the European powers ‘to disrupt the business model of the smugglers’ through military force, whilst remaining complicit in the racialised labour practices and human rights disasters facing those fleeing to Europe, has very specific historical echoes.

Britain and the US abolished their transatlantic slave trades in 1807/8 in a context of imperial war, and long before serious consideration of ending slavery itself was in sight. The US immediately protected its slave plantation complex by using the moment to enclose the seas in the name of legitimising a domestic slave trade along its Atlantic borders – Baltimore boomed. Britain launched itself on an international crusade to persuade other European nations to abolish their trades. The British Abolition Act included an under-resourced naval humanitarian mission setting out instructions for the arbitration and punishment of illegally operating slave traders, and also short-term guidelines for what to do with kidnapped Africans rescued from the illegal ships. In the context of the Napoleonic wars, the British state had been purchasing enslaved Africans to serve its military interests in the Caribbean.[15] With the prospect of this source of labour ending, the Abolition Act stipulated that rescued Africans would either be pressed into the Army or Navy or involuntarily indentured, in Sierra Leone or the Caribbean, for a maximum of fourteen years. In the Caribbean, colonial officials protested the arrival of unenslaved but nonetheless bound Africans in the midst of their slave economies, arguing that they would be a disruptive element. They were disruptive insofar as they quickly learned that their rescue meant that they would be treated as if they were enslaved, and they resisted.

To note the terms of the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade in the current context is not simply to make trite historical analogies or to wallow in historical irony. Nor is it to take up the ‘new abolitionist’ and imperialist narrative that deplores the symptoms but misses the cause. It is, rather, to note a particular moment in forging the continuum of coerced, and raced, labour relations that developed within and out of slavery. The ancient practice of indentureship, that bound the first colonial labourers in the Americas was again tested on the ‘rescued’ Africans. It came to stand for emancipation in the British Caribbean between 1833 and 1838, and then structured the terms under which further huge waves of racialised labour migration arrived in the Caribbean through the nineteenth century and beyond. As Peter Linebaugh observes, the Maryland judge who reminded Benjamin Lundy that the domestic slave trade helped to clear Maryland of ‘a great many rogues and vagabonds’ had used an ancient terminology. It was a terminology that had designated the sixteenth-century unemployed as superfluous vagrants at a time when capital was creating an industrial labour force and criminalising those who resisted, either actively or passively. Today’s African migrants and refugees are not analogous to sixteenth-century English peasants or to the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century enslaved or indentured Africans. They are, however, conceived of as modern ‘rogues and vagabonds’. With their commons and cultures expropriated by imperialist war, politically induced famine and multinational land-grabs, they are subsequently drowned. If not drowned, they are criminalised for attempting to sail for what they perceive as freedom.[16]

Campaigners for reparations might not want to speak about ‘modern-day slavery’ because discussions about modern slavery have too often had the effect of glossing or diluting a recognition of the history and legacies of slavery. The silence might be expedient but perhaps this is to concede too readily to the terms on which they are forced to debate. The language of the reparatory is constituted within the discourse of human rights that has itself transformed the political terrain. As many have observed, the idea of reparation is a concept of justice that has purchase in a world where the idea of revolution as a way of overcoming the past no longer seems a possible way of thinking about the future. As David Scott notes, it is perhaps this context that has ‘made the language of trauma – and the memory work that sustains it – so arresting for thinking about the persistence of harms resulting from the perpetration of historical wrongs’.[17]

Scott is right insofar as trauma is a contemporary structure of feeling, which functions as a cultural dominant within which the reparative organises modes of remembrance in relation to inherited experience. It structures cultural memory around guilt, loss and pain by producing divisive and fragmented conditions that work to legitimise, privatise and contain that structure of feeling within a redemptive narrative of ‘working through’. Yet reparative history is about more than contemplating injury or apportioning blame. It is about agency, and it can be wedded to a form of memory energised by the emancipatory activism, solidarity and political struggles of the past. Any form of politics begins with the articulation of a particular grievance but it does not need to become enmired there.

The concept of the reparative – thought through historically – enables the work of mourning to be connected to the politics of material redress by refusing to understand the history of ‘race’, imperialism and slavery from the vantage point of contemporary progress and reason. The point here is to excavate histories of resistance, solidarity and collectivity as vital for the now. The liberal narratives, which would monumentalise and domesticate histories of slavery and colonialism, struggle with acknowledging the presence of black radicalism, black rebellion, anti-colonial struggle and the alternative cultural memories that are precisely being registered on the streets of Baltimore and in the voices of the Black Lives Matter movement.  Reparative history is concerned with grievance as the starting point of politics, with no easy relation to a restorative project, but recognising grievance or rage as the agent of history. It is concerned with making ‘race’ visible, and with critically engaging with the giddy promises of liberalism, not in terms of the claims that liberalism makes for itself but with the radical re-appropriation of those claims by countless subjects of racialised capitalism. This project is, of course, an acknowledgement of those grievances but it is, concomitantly, an acknowledgement of the complex solidarities that were created in the struggles against slavery and colonialism. It is thus the dialectical interconnections between the colonies, the ex-colonies and the metropole which complicate discrete ethno- centric understandings of the past that underpin the essays in this collection.

Reparative history is concerned with grievance as the starting point of politics, with no easy relation to a restorative project, but recognising grievance or rage as the agent of history. It is concerned with making ‘race’ visible, and with critically engaging with the giddy promises of liberalism, not in terms of the claims that liberalism makes for itself but with the radical re-appropriation of those claims by countless subjects of racialised capitalism. This project is, of course, an acknowledgement of those grievances but it is, concomitantly, an acknowledgement of the complex solidarities that were created in the struggles against slavery and colonialism. It is thus the dialectical interconnections between the colonies, the ex-colonies and the metropole which complicate discrete ethno- centric understandings of the past that underpin the essays in this collection.

***

The essays published here emerged from a research symposium, ‘Reparative histories: Radical Narratives of “Race” and Resistance’, held at the University of Brighton in September 2014.[18] The rich set of discussions which materialised at this event confirmed our conviction that the idea of ‘reparative history’ is a challenging and productive one. As far as we are aware, there is no extant body of work concerning the idea of reparative history. There is, of course, a long tradition of radical historiography. Indeed, one of our key questions concerned the nature and extent of the relationship between the so-called ‘reparative’ and the ‘radical’. As suggested by this introduction, the aim is not to offer any particular abstract, schematic or discrete definition of what the term ‘reparative history’ might, or should, mean. Instead, all of the papers here engage with the way in which the concept of ‘the reparative’ is necessarily shaped by the political, cultural, historical and social contexts in which it is constituted and mobilised. We chose Race & Class for reasons which should be obvious but nevertheless need articulation here in terms of the important tradition of radical black historiography with which this journal is so strongly identified. The focus in many of the essays in this issue on the importance of black workers as instrumental to the forging of a class politics which has transformed understandings of race, agency and solidarity in the metropole is one that has been forged – over several decades – in the pages of this journal.[19]

All of these articles challenge dominant historical narratives in different ways: ‘reparative histories’ is the organising concept. We are not giving a definitive gloss to the term, nor are we suggesting that its meaning is so fluid as to evade concrete articulations of how we understand the process of history-making as a deeply political project. The politics of the present moment demand a rigorous investigation of how certain stories of the past are mobilised, and how certain histories are shaped in the light of contemporary concerns. Whilst historiography has been cognisant of this process for some time, the current wider preoccupation with ‘redress’ explicitly asks historical questions which underline and emphasise this dialectical process. Moreover, this approach opens up a space for a radical rethinking of the paradigms that have hitherto organised our understandings of ‘race’, class, agency and colonialism.

Please note that this issue of Race & Class is being launched at a meeting on 23 February.

Related links

Buy the issue here

Get a subscription here or here

View details about the launch meeting on 23 February here