Below we reproduce an interview with Jean Casella from the US-based Solitary Watch by Luk Vervaet, first published on his blog. Although solitary confinement is not used as frequently as in the US, the UK has four close supervision centres.[1] A recent Prisons & Probation Ombudsman report highlighted the high number of suicides of those prisoners held in segregation.[2]

In May 2015, Solitary Watch co-director Jean Casella and her colleague Aviva Stahl were on a reporting trip in the United Kingdom. Solitary Watch’s James Ridgeway and Jean Casella have pioneered research and interest on solitary confinement and emerged as world experts on the subject. Luk Vervaet met Jean Casella in London for an exclusive and extended interview on the historical and present practices of solitary confinement, the most extreme form of punishment for tens of thousands of prisoners in the US.

Luk Vervaet (LV): When did you start Solitary Watch?

Jean Casella (JC): Solitary Watch began at the end of 1999. The genesis of the project really originated with James Ridgeway, the co-director of Solitary Watch along with me. James was working at that time for Mother Jones, a progressive magazine in the United States, when he was assigned to write a story about the Angola 3.

The Angola 3 were three guys from the Black Panthers who, in prison, were accused of the murder of a prison guard, and placed in solitary confinement. It was a vindictive punishment that was meant to go on indefinitely, and, in fact, lasted for over forty years. At the time James was carrying out his assignment, one of the Angola 3, Robert King, had been released. Another one, Herman Wallace unfortunately died in 2013 just days after his release, and, the third, Albert Woodfox is currently in his forty-third year of solitary confinement in the Louisiana prison system. During the research on this article, we learned that there were tens of thousands of people, like the Angola 3, incarcerated in solitary confinement.

LV: How do you define solitary confinement?

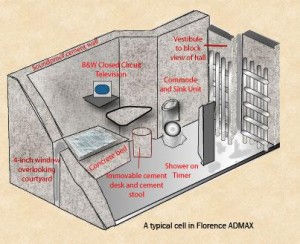

JC: We define solitary confinement as spending 22 to 23 hours a day in a cell, alone, usually in a state of pretty extreme sensory deprivation, lack of human contact, fed by prison guards, with the only contact through a slot in the cell door, which have no bars but are made out of solid steel. I can’t give you a uniform picture of what constitutes solitary confinement, because in the US we don’t have one prison system, we have 51 prison systems, because each of the fifty states runs its own prisons, and the federal government also has its own prisons too.

But, what’s common to the regime is extreme isolation and sensory deprivation. There is little programming, treatment and education in the American prison system, but people in solitary don’t even have access to that. We heard stories about supposed psychiatric treatment taking place through the slot in the door. Mental health staff would come around, checking up on how people were doing, and what that consisted of was shouting through the door. This is even true for medical care. I have a friend who was in solitary for five years, he’s out now and he tells a story about getting his insulin injection each day by putting his arm through the slot. And the nurse on the other side would give him the injection. Everything has been taken to an extreme.

But, what’s common to the regime is extreme isolation and sensory deprivation. There is little programming, treatment and education in the American prison system, but people in solitary don’t even have access to that. We heard stories about supposed psychiatric treatment taking place through the slot in the door. Mental health staff would come around, checking up on how people were doing, and what that consisted of was shouting through the door. This is even true for medical care. I have a friend who was in solitary for five years, he’s out now and he tells a story about getting his insulin injection each day by putting his arm through the slot. And the nurse on the other side would give him the injection. Everything has been taken to an extreme.

LV: Are there official numbers on how many prisoners are living in a solitary regime in the US?

JC: Some 80,000, that’s if you follow certain statistics, that came out of a government survey on prisons ten years ago. On one given day, they asked the prison authorities within the fifty states, as well as the federal system, how many people were in solitary confinement on that particular day. So it was self-reported. We know, for instance, that they didn’t survey in local jails where people are held on remand for short sentences; nor did they survey in immigration detention centres, where we know solitary is also used. We estimate that the total is probably well over 100,000. There have been some little reforms since that time, but we don’t believe that this brought down the number significantly, maybe by a few thousand.

LV: So the Angola 3 was the starting point for a broader campaign and project?

JC: Our idea was that this was really a domestic human rights crisis that was going on in the United States. Some people were very upset about what was going on at Guantánamo. And yet we had similar conditions in prisons in our own backyard, and the conditions at Guantánamo were partly reflecting this. Right in our midst, these people were also living. There is a prison in lower Manhattan in New York where prisoners are held in solitary confinement.

LV: How many people in solitary confinement does your publication reach?

JC: We have correspondence by letter with about 200 people in solitary. And then there are some 1,500 who are receiving our quarterly newsletter, holiday cards, etc. You must realise that even if these numbers were bigger, we can only reach about a third of the people in solitary. One third are so severely mentally ill that you can’t possibly communicate with them. Another third are illiterate. Then there is no way of communicating with them.

JC: We have correspondence by letter with about 200 people in solitary. And then there are some 1,500 who are receiving our quarterly newsletter, holiday cards, etc. You must realise that even if these numbers were bigger, we can only reach about a third of the people in solitary. One third are so severely mentally ill that you can’t possibly communicate with them. Another third are illiterate. Then there is no way of communicating with them.

LV: I heard about a prisoner called William Blake, a writer in solitary confinement you are working with?

JC: He was a guy, very young, in his early twenties when he appeared before the court on a minor drug charge. He panicked and he grabbed the gun from a sheriff’s deputy and he shot him, trying to escape. But naturally he didn’t escape. So he was a cop-killer and an escape risk. He was sentenced to 77 years to life. And he was immediately put in solitary confinement. This happened in New York state, in our liberal state, far from the worst prison system in the country.

He’s been in solitary for about twenty-seven years now. Lives in a 7 by 10 cell.

He is a remarkable writer. Writing is everything to him, publishing his work and becoming a real author. His full name is William Blake, just like the poet. He wrote a piece on solitary confinement that we published called ‘A sentence worse than death’. It went viral, on the internet, the circulation grew and grew and eventually it had around 600,000 hits just on our website. It was translated into several languages, including Dutch. Suddenly, he had people from all over the world writing to him. He became a kind of celebrity.

So what the prison did with this celebrity was, they moved him. He had been in that prison for the last five to seven years, and they decided it was time to move him to another prison. Letters are not forwarded in the prison system. So everyone who was writing to him was blocked. We put a post on Solitary Watch, that he had been moved, but he hasn’t the number of people writing to him like before. In addition to that he was working on a novel, hand-written, because there is no access to a typewriter, he had 1,500 handwritten pages of the first draft and 700 of the second draft and they threw it all away. They just said it was trash. They threw away many of his books. When anyone develops a kind of personal empowerment, the instinct of the prison system is to crush that. People like him are really unusual because he doesn’t have any severe psychological damage, he’s really, really strong. I’m sure he has some effects, everyone does, but it hasn’t made him completely crazy.

LV: You are working on editing a book on solitary confinement?

LV: You are working on editing a book on solitary confinement?

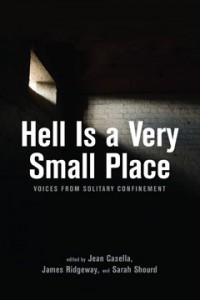

JC: Eventually we would like to work on a book with William Blake, because I think he has a book in him. But the first thing we have done is edit a collection of the writing of fifteen people in solitary confinement, plus some essays by experts on the effects of solitary. The book has been taken by a publisher and will come out in February next year. The title is: Hell is a very small place.

LV: Where does the rationale for this extreme form of punishment come from?

JC: The starting point for the use of solitary confinement was actually in nineteenth century Philadelphia where solitary confinement was introduced by the Quakers as a positive and humane alternative to physical punishment such as flogging or being held in the stocks. It was also seen as an alternative to locking people up in disgusting conditions within disease-ridden local jails, dungeon-jails. So they invented the word penitentiary and constructed the Eastern State Penitentiary. The expectation was that people, once isolated, would contemplate and turn to God and experience feelings of penitence for their sins. Complete isolation and enforced idleness provided the best environment for this, or so they thought. Well, it didn’t work out very well, as people started losing their minds!

By the beginning of the twentieth century, the penitentiary model of imprisonment had largely been abandoned. Other conceptions were favoured: still a hard regime, but not an isolating one, and an emphasis on hard work. There were a few exceptions, such as Alcatraz, where people who were considered extreme risks were placed in solitary, but never to the extent of what we experience today. There was far more communication between prisoners compared to what happens today within our modern system of solitary confinement.

The rebirth of solitary was to begin in the 1980s at Marion, a federal prison in Illinois, which had a reputation as plagued by warring prison gangs. After one week, in which two prison guards were killed by different gang members, the whole prison was placed on lockdown, which means everybody in their cells, all programmes, exercise, education, cancelled – and it never came out of lockdown again. You know, it’s very common to have a lockdown for a day, or for 24 hours, after an escape attempt or something like that. But this was a permanent lockdown and it just never came to an end.

The rebirth of solitary was to begin in the 1980s at Marion, a federal prison in Illinois, which had a reputation as plagued by warring prison gangs. After one week, in which two prison guards were killed by different gang members, the whole prison was placed on lockdown, which means everybody in their cells, all programmes, exercise, education, cancelled – and it never came out of lockdown again. You know, it’s very common to have a lockdown for a day, or for 24 hours, after an escape attempt or something like that. But this was a permanent lockdown and it just never came to an end.

LV: So maybe the first question should be, what really brought about this punitive turn in US prison policy, leading to this second phase in the use of solitary confinement?

JC: It’s kind of a mystery to me why this tremendous law and order backlash happened in the US and to a certain extent in Europe in the 1980s, growing ever more intense in the ’90s. There are all kinds of explanations as to the underlying causes. Some say it was the end of the Cold War, and the need to look inside for our enemies. There was also a spike in crime in the seventies. The backlash against the Civil Rights movement, linked to the racial fears of white people suddenly confronted with people they oppressed for centuries rising up, is another possibility.

JC: It’s kind of a mystery to me why this tremendous law and order backlash happened in the US and to a certain extent in Europe in the 1980s, growing ever more intense in the ’90s. There are all kinds of explanations as to the underlying causes. Some say it was the end of the Cold War, and the need to look inside for our enemies. There was also a spike in crime in the seventies. The backlash against the Civil Rights movement, linked to the racial fears of white people suddenly confronted with people they oppressed for centuries rising up, is another possibility.

But whatever the reasons, one thing is clear, that there was enormous and exponential growth in the prison population. They couldn’t build prisons fast enough to hold all the people. And as there was overcrowding, there was also a need to control these populations. Then, there was the mentality of the general public which was to let the prison system do whatever it wanted. Solitary confinement is an easy, lazy way to maintain order, to control these populations. It’s a way to punish people that are troubling in either a major or minor way. It’s a way for guards to take revenge on people they don’t like. There are definitely racial disparities in the number of people of colour in solitary confinement. The number of people of colour in the US prison population is already wildly disproportionate, but within solitary confinement this disproportion is even greater still.

LV: So the renewal of solitary confinement is linked to the need to maintain control in overcrowded prisons? But is this the only explanation?

JC: I think there is something more. Something that’s going on that hasn’t anything to do with any practicalities, like maintaining order or anything else. It seems as if there is a kind of pure evil going on here and I don’t use this term very often. I’m not a psychologist or a philosopher but it seems to me that what is going on here is some kind of elemental desire to break men, to punish them as intensely as possible.

They use arguments to justify their actions around particular people and particular offences. For instance, they ask ‘what do we do with a prisoner who killed another prisoner, or a prison guard, or with a person who is a prison rapist?’ First of all, that’s about five per cent, or maybe even less of all the tens of thousands of people placed in solitary confinement. And even with people who may need to be separated from the general prison population and placed in a more secure environment, why can’t they be allowed to make a phone call to their mothers? Most of these things are so arbitrary. There are so many rules. For instance, I’m involved in a project were photographers are taking pictures for people on solitary. Prisoners can request photos that they would like to have in their cell—photos of anything they would like to see—and photographers outside will take the photos. But in Illinois there are specific rules that state that these pictures cannot measure more than 4 by 6 inches and, furthermore, they are only allowed to have six photos in their cells at any one time. So, lets say, they have six photos of their family. So when the photographer sends in the new photo, in order to receive it, they have to give up an existing picture of a family member. They can’t put them all on their wall. So I’m asking myself, why? This is just sheer cruelty.

They use arguments to justify their actions around particular people and particular offences. For instance, they ask ‘what do we do with a prisoner who killed another prisoner, or a prison guard, or with a person who is a prison rapist?’ First of all, that’s about five per cent, or maybe even less of all the tens of thousands of people placed in solitary confinement. And even with people who may need to be separated from the general prison population and placed in a more secure environment, why can’t they be allowed to make a phone call to their mothers? Most of these things are so arbitrary. There are so many rules. For instance, I’m involved in a project were photographers are taking pictures for people on solitary. Prisoners can request photos that they would like to have in their cell—photos of anything they would like to see—and photographers outside will take the photos. But in Illinois there are specific rules that state that these pictures cannot measure more than 4 by 6 inches and, furthermore, they are only allowed to have six photos in their cells at any one time. So, lets say, they have six photos of their family. So when the photographer sends in the new photo, in order to receive it, they have to give up an existing picture of a family member. They can’t put them all on their wall. So I’m asking myself, why? This is just sheer cruelty.

LV: Is this a form of hidden death penalty? Killing people socially, emotionally?

JC: For some it is. For many people quite literally so. About five to ten per cent of the prison population is in solitary confinement and we know that fifty per cent of all suicides happen in solitary confinement.

LV: When we see television programs like Lock Down on the National Geographic channel, prisoners in solitary are presented as the worst of the worst, as monsters and animals. And the conclusion that is drawn from this is that the only possible option for such people is to put them in isolation cells.

JC: Well first of all, I like animals very much and sometimes I think that people should behave more like animals! What you have to realise when you see these kind of television programmes is that these people have been totally deprived of their humanity, and if you have been so dehumanised how on earth are you meant to show the world your humanity, particularly when faced by a TV camera? Nonetheless, I believe everyone has humanity.  I also believe that solitary is torture. And so it’s like the question of the death penalty. The wrong questions are being asked. We shouldn’t be asking, does this person deserve to die? Rather, the question is, what gives us the right to kill him? So instead of asking, does this person deserve to exist within these conditions, we should ask ourselves, do we want to live in a society that tortures its own citizens? There is no reason for this, it serves no purpose. It doesn’t reduce violence. Studies have shown that at best it has no effect whatsoever on violence and, at worst, it increases recidivism and violence. People coming out of solitary are more likely to return to prison within the first three years of their release. So why are we doing this, it doesn’t do anything positive – and it’s torture.

I also believe that solitary is torture. And so it’s like the question of the death penalty. The wrong questions are being asked. We shouldn’t be asking, does this person deserve to die? Rather, the question is, what gives us the right to kill him? So instead of asking, does this person deserve to exist within these conditions, we should ask ourselves, do we want to live in a society that tortures its own citizens? There is no reason for this, it serves no purpose. It doesn’t reduce violence. Studies have shown that at best it has no effect whatsoever on violence and, at worst, it increases recidivism and violence. People coming out of solitary are more likely to return to prison within the first three years of their release. So why are we doing this, it doesn’t do anything positive – and it’s torture.

I don’t approve of torture not even for the ‘worst of the worst’.

The reality is it’s the most vulnerable groups, the most disadvantaged people, people with development or learning disabilities, mental illness, problems associated with substance abuse, who are put in solitary. As are LGBT people, especially trans people, supposedly for their own protection and yet, once there, they are raped by guards because they look like women.

The psychiatrist and author of Prison Madness, Terry Kupers, talks about disappearing people. They used to talk, in countries like Chile, about ‘the disappeared’. Disappearing people is the government’s way of getting rid of people it is inconvenient to have in society. And that’s similar to ideas developed by my colleague James Ridgeway about banishment and internal exile. You can’t ship them off to Australia any more, as the British used to do. We don’t have any penal colonies any more. So we place them in permanent exile inside our prisons.

The psychiatrist and author of Prison Madness, Terry Kupers, talks about disappearing people. They used to talk, in countries like Chile, about ‘the disappeared’. Disappearing people is the government’s way of getting rid of people it is inconvenient to have in society. And that’s similar to ideas developed by my colleague James Ridgeway about banishment and internal exile. You can’t ship them off to Australia any more, as the British used to do. We don’t have any penal colonies any more. So we place them in permanent exile inside our prisons.

LV: Solitary Watch has chosen over the last six years to focus uniquely on the issue of solitary confinement. You have pioneered research and interest on this issue and emerged as a world reference on this subject. What do you see as the future perspectives for your work?

JC: We now see that quite a number of advocacy groups are taking up the issue. For instance, the American Civil Liberties Union has a big campaign against solitary. Amnesty International has also done some work. Religious organisations like the National Religious Campaign Against Torture (NRCAT) which started out as an anti- Guantánamo group are now very much involved in domestic prison system issues, including solitary confinement. That’s really good to see. One thing we are trying to do with the 1,500 people we are in contact with in solitary, is to say, give twenty-five names of prisoners in solitary to a church and ask that the members of the congregation write letters to these guys. We tell them, ‘no letter that you ever write will be as valued as this letter’. Amongst academics, I like the work of people like Lisa Guenther, who is a philosopher. She published a book called Solitary confinement: social death and its afterlives. It’s quite an amazing book, and she asks the question, ‘We know solitary confinement annihilates the minds of its victims – but what does it do to the rest of us?’

LV: What about the alternatives you are putting forward?

JC: We have just started to study this. You see, all our attention up to now has been focused on the question ‘how can we expose this, show people why it’s bad’. Now other people have taken the banner and are fighting the cause, even some policy-makers and politicians.

We need to start responding to the question: what will we do instead? There are not a lot of answers coming from the United States. There are a few States that have done some interesting pilot projects in this respect, and we intend to see what’s been put in place in Washington and in New Mexico. We also know that we have to look abroad. Not just to see if they have better conditions in solitary, but also to go back to basics, to look at the kinds of people who get put it solitary in the US, and to see what happens to similar people in other societies?

Next week, in the UK, we are going to see what is called a ‘diversion programme’ which the British government is running through the auspices of the National Health System (NHS). Here, social workers and nurses are brought into police stations and into the courts. The idea is to identify people with an obvious mental illnesses or substance abuse problem and provide the option that they are handed over to this programme instead of locking them up for some minor thing, like pissing in public, as happens in the US. Like I said before, people with mental illnesses constitute a third of all people in solitary in the US, and they are the people who are suffering the most. So programmes such as this could make great difference. We must search for other ways to treat people, first of all to keep them out of the criminal justice system and second to keep them out of solitary.

LV: You place a great stress on simple reforms, like giving those in solitary the right to make a phone call. Some people might say that this is just a minor questions, can you explain why for you this is so important?

JC: First of all, the assumption is now made that unless you can prove that someone needs something, they don’t need to have it. In fact, it should be the opposite. As long as you cannot provide a reason for depriving someone of something, then there can be no justification for removing a person’s rights, depriving them of their reading material, for instance, or their right to make a phone call.

JC: First of all, the assumption is now made that unless you can prove that someone needs something, they don’t need to have it. In fact, it should be the opposite. As long as you cannot provide a reason for depriving someone of something, then there can be no justification for removing a person’s rights, depriving them of their reading material, for instance, or their right to make a phone call.

Second, for the very few people who need to be separated from others, because they are a genuine danger, ways must be found to humanise their environment. A phone call is one way to do that. The so-called monster you see on TV might have a mother or a sister somewhere who can be a humanising force. We should be encouraging that. People don’t need less, they need more. More individualised attention, more programming. So instead of going in solitary they should go in units where there is more care.

LV: Is there a danger that a campaign against solitary confinement could end up glossing over the problems inherent within the so-called ‘normal’ prison system, which seem okay by comparison?

JC: The question you ask is often seen as the dilemma between an abolitionist perspective on prisons versus a reformist position. Personally, I don’t see the State being overthrown in the US in the near future (laughs), I don’t see the prison system crumbling to the ground. What do we do in the meantime, when people are really suffering? Solitary is the prison within the prison. But if we start here, in the prison within the prison, we can also tackle the problems inherent within the prison system as a whole. So you start by asking the question, why are we putting people with mental illness in solitary? And then the question raises itself, why are we putting them in prison at all? We are dealing with the most disadvantaged people in society who are in prison, so let’s give them more attention. Just like the people in solitary need more attention. If we give them more attention earlier, they won’t end up in prison. So I don’t see it as a terrible dilemma.

Related links

Luk Vervaet, The Guantánamo-isation of Belgium, Race & Class (Vol 56, No. 5, 2015)