As the family of Mark Duggan launch a judicial review of the inquest verdict, IRR News examines the wider context of the death.

On 4 August 2011, Mark Duggan got out of a taxi on Ferry Lane in Tottenham and was shot dead by armed police: within hours, stories about a dramatic ‘shootout’, a ‘violent gangster’, and gangland ‘revenge killings’ began to circulate. Two years later in September 2013, the inquest jury was told that they were on a ‘quest to find the truth’,[1] a process that lasted for three months and involved ninety-three witnesses.

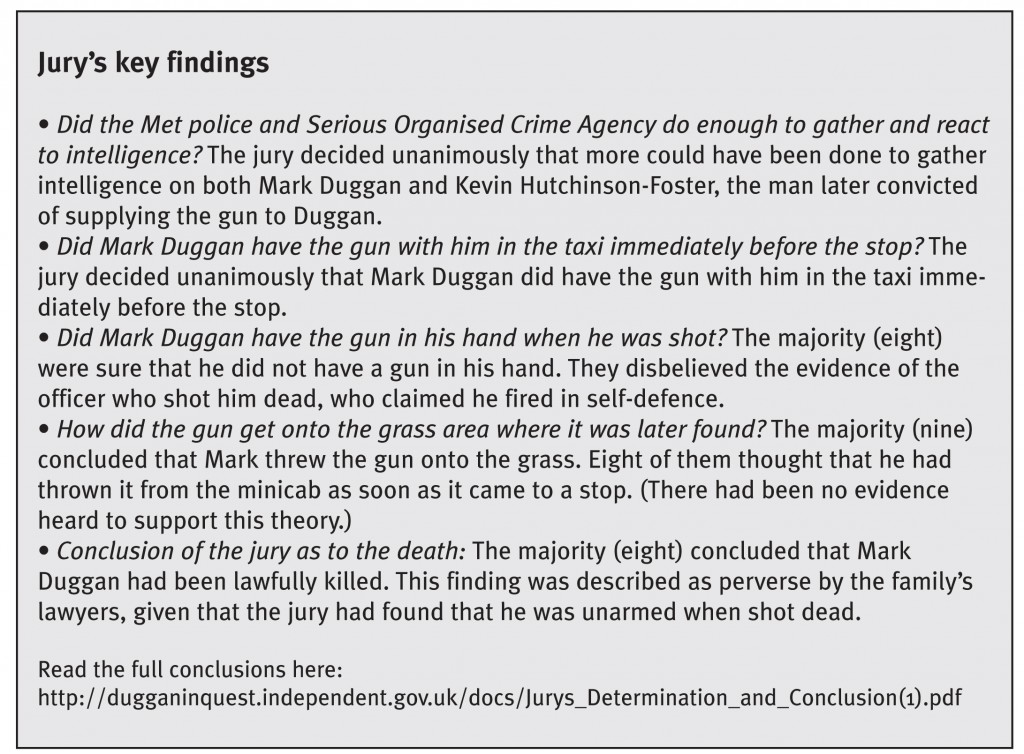

In January 2014, after several days of deliberations, the jury eventually delivered their verdict of lawful killing, and the public gallery erupted in disbelief and outrage. All ten jurors agreed that there had been a gun in the taxi with Mark Duggan. Eight of them disbelieved the evidence of the police marksman who shot him, and were sure the gun was not in his hands when he was shot dead. But despite this, an 8-2 majority concluded that he had been killed lawfully. Their explanation for the whereabouts of the gun was that he must have thrown it from the taxi before it was surrounded – but no witnesses gave evidence to support this idea. Immediately, the family’s legal team asked the high court to quash the verdict as perverse, arguing that Judge Cutler, presiding over the inquest, should have provided clearer direction to the jury. The inquest also raised questions about the possibility of police officers conferring as they produced their statements, and the family was given permission to challenge these practices in March 2014. Despite the lengthy inquest and the long wait, there are still many unanswered questions.

In January 2014, after several days of deliberations, the jury eventually delivered their verdict of lawful killing, and the public gallery erupted in disbelief and outrage. All ten jurors agreed that there had been a gun in the taxi with Mark Duggan. Eight of them disbelieved the evidence of the police marksman who shot him, and were sure the gun was not in his hands when he was shot dead. But despite this, an 8-2 majority concluded that he had been killed lawfully. Their explanation for the whereabouts of the gun was that he must have thrown it from the taxi before it was surrounded – but no witnesses gave evidence to support this idea. Immediately, the family’s legal team asked the high court to quash the verdict as perverse, arguing that Judge Cutler, presiding over the inquest, should have provided clearer direction to the jury. The inquest also raised questions about the possibility of police officers conferring as they produced their statements, and the family was given permission to challenge these practices in March 2014. Despite the lengthy inquest and the long wait, there are still many unanswered questions.

What is known is that the death of Mark Duggan will go down in history as the event that ‘sparked’ the August 2011 riots. As well as understanding this important connection, we also need to be aware that the wider political context of the riots has had implications for the subsequent investigation of the shooting of Mark Duggan. Right from the beginning, the police, Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC) and judiciary, as well as the media, have played important roles in determining how the shooting was framed, long before the jury sat down in the courtroom.

Trident and the secret evidence regime

The policing operation that led to Mark Duggan’s death was run by Trident, a unit within the Metropolitan Police specialising in gun crime within London’s black community. Trident was set up in 1998 following a series of shootings and murders in Lambeth and Brent. At the time, there was widespread concern within the black community about these shootings, and so there was support for a dedicated unit to tackle gun crime. An Independent Advisory Group (IAG) was set up to ensure community oversight and accountability in this most sensitive area of policing. The IAG was often very vocal in its criticism of Trident’s operations, particularly its mostly white workforce.[2] Over the years Trident operations shifted. As well as ‘reactive’ investigations of shootings, it began using ‘proactive’ teams conducting covert investigations of particular individuals suspected of having connections to gun crime. [3]

Legislation passed over the last fifteen years has progressively increased the use of secret evidence, which has significantly undermined the accountability of policing operations. In 2008 legislation was passed enabling the use of evidence in court from ‘anonymous witnesses’ to secure convictions.[4] And eight years before that, the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (RIPA) 2000 was passed, protecting so-called ‘intercept evidence’ (phone taps, for example) from being heard in court. It was the use of secret evidence under RIPA powers that caused the collapse of the inquest into the death of Azelle Rodney, a black man who was shot dead by police officers in April 2005 in north London. During the original inquest the Rodney family demanded to hear evidence about the police pursuit that the police were withholding. The inquest could not continue, and it was eventually decided to hold an Inquiry that had greater powers to close hearings, restrict attendance and withhold sensitive evidence.

The suppression of some of the evidence relating to Azelle Rodney’s death, and the difficulties that ensued, were cited by the government as a reason to extend the use of secret evidence to civil proceedings, including inquests. These proposals were eventually brought in with the Justice and Security Act, which came into law in 2013, although due to widespread objection they excluded inquests (see ‘Secret justice = injustice’, IRR News 23 February 2012). However, the Azelle Rodney Inquiry chair Sir Christopher Holland appeared to undermine this assertion when he said that much of the secret evidence did not need to be secret. The Inquiry eventually found in 2013, nine years after his death, that he had been unlawfully killed.

The suppression of some of the evidence relating to Azelle Rodney’s death, and the difficulties that ensued, were cited by the government as a reason to extend the use of secret evidence to civil proceedings, including inquests. These proposals were eventually brought in with the Justice and Security Act, which came into law in 2013, although due to widespread objection they excluded inquests (see ‘Secret justice = injustice’, IRR News 23 February 2012). However, the Azelle Rodney Inquiry chair Sir Christopher Holland appeared to undermine this assertion when he said that much of the secret evidence did not need to be secret. The Inquiry eventually found in 2013, nine years after his death, that he had been unlawfully killed.

By the time the circumstances surrounding Mark Duggan’s death came under the spotlight, the secret evidence regime had become established, and for some time it was uncertain whether there would be an inquest at all. Intelligence for Trident’s operations came from ‘intercept evidence’ obtained by the Serious Organised Crime Agency (SOCA, merged into the National Crime Agency since October 2013), and so was protected under RIPA legislation. The inquest had to be stopped and re-started, with the original coroner replaced by Judge Cutler, who could consider the secret evidence.

Facts and conjecture

According to evidence given by its senior investigating officer at the inquest, Operation Dibri was a Trident investigation that had been running since November 2008, focused on ‘dismantling’ Tottenham Man Dem (TMD), a group the police said was involved in the supply of guns and Class A drugs. Dibri focused on around 100 people, with a ‘core’ of around forty-eight people.

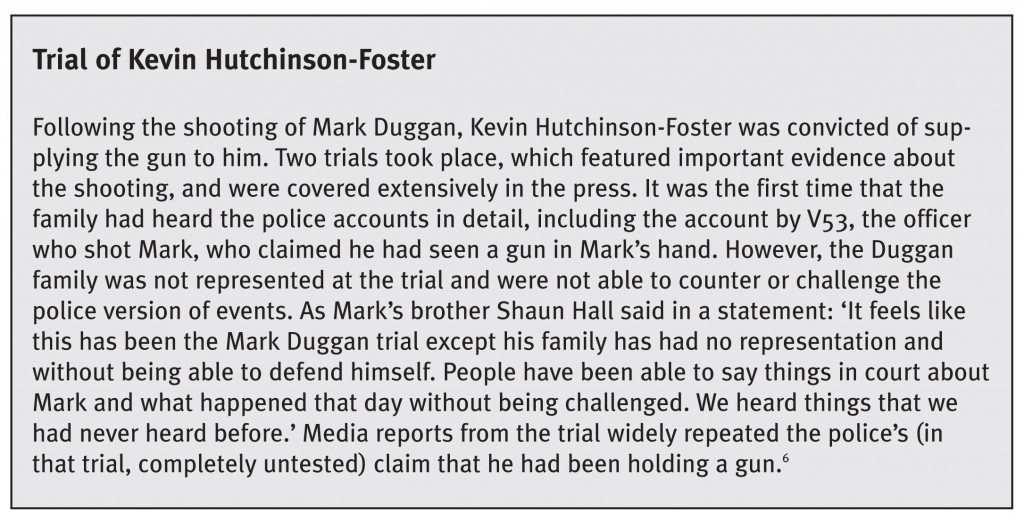

While giving evidence about the subjects of Operation Dibri, including Mark Duggan, officers made assertions about crimes they thought he had committed, and about his being a ‘senior’ member of the gang. Due to the fact that the intelligence was exempt from being scrutinised in court (due to the RIPA legislation), most of the assertions remain untested. What is known is that Mark Duggan had never spent time in prison, and that his criminal record consisted of two minor convictions, one for receiving stolen goods and one for possession of cannabis, the most recent in 2007. Both had attracted only small fines. Although police made a variety of other assertions, about drugs being stored at Mark Duggan’s home, that he had fired shots in a car park, that they had a ‘wealth’ of intelligence that he had ready access to guns, they also admitted that until 4 August, they did not have evidence necessary to arrest him. Some of the intelligence, they said, was of very poor quality, equivalent to something being said to Crimestoppers by an anonymous caller who had overheard something in a pub. The claims about Mark Duggan being a ‘senior member’ of a gang were made time and time again by the police, during the trial of the man convicted of supplying the gun (Kevin Hutchinson-Foster, see box), up to and during the inquest, and on each of these occasions were repeated by the media as fact[5].

The shooting

According to evidence heard at the inquest, Trident’s Operation Dibri planned a four-day operation from 3-7 August 2011 to recover guns from around six people, including Mark Duggan. This operation involved officers from Trident working together with specialist firearms officers (CO19) and armed surveillance officers (SCD 11). The CO19 officers were plain-clothed officers armed with two guns and a taser, who had responsibility for carrying out the operation to recover the guns.[7] The operation had planned to target nightclubs, so most of the activity was due to take place in the evening. Surveillance officers had tracked Mark on the evening of 3 August before losing him. On the afternoon of 4 August at around 5.15pm, the police received intelligence that suggested he planned to take possession of a gun from an acquaintance that evening. He was followed to an address in Leyton by the surveillance officers, who said they observed him before the minicab continued towards Tottenham, still being tailed. More intelligence was then received that confirmed Duggan had collected a gun. Meanwhile, Trident officers attended a briefing and then deployed towards Tottenham in a convoy of cars to intercept the minicab, accompanied by CO19 and SCD11. At 6pm, ‘state amber’ was called by the Tactical Firearms Commander (known as Z51), meaning there was enough intelligence to arrest, and responsibility for carrying out the operation passed to the leader of the firearms team, known as V59. Thirteen minutes later, the officer leading the interception, W42 called ‘state red’ over the radio, and the order ‘strike, strike’. The hard stop itself was carried out on Ferry Lane, Tottenham, next to a bus stop and not far from Tottenham Hale tube station.

Officers in three cars surrounded the minicab, forcing it to stop, then got out and surrounded it on foot, shouting and pointing their loaded weapons at Mark Duggan and the minicab driver, a tactic designed to ‘shock and awe’ suspects into submission. It didn’t work: Mark Duggan got out of the car onto the pavement, at which point he was shot twice, once in the right arm, causing a minor wound, and also in the chest, which was fatal. One of the bullets passed through his body and struck a police officer (W42), who was not injured because it hit his radio. CPR was performed on Mark, but he was pronounced dead on the scene at 6.41pm.

Aftermath

In the immediate aftermath of the death, the family were not officially informed by the police, in contravention of statutory obligations. As a result, there was confusion on the part of the family over whether the dead man was actually Mark. His sister, brother and Semone Wilson (his fiancée) had attended the scene, but said they left unsure whether the dead man was Mark, as they had been told the dead man was Asian (see the IPCC report into the complaint). At least one member of the family drove to Whitechapel hospital believing that he had been taken there alive by air ambulance, only to find that it was actually the injured firearms officer who had been transported, statements read out at the inquest revealed. Because they had not been formally told, it was difficult for them to comprehend what had happened. Pamela Duggan said: ‘A mother’s worst nightmare is the police coming to your door to tell you that your child is dead. Because this did not happen, I believed the worst had not happened.’ Frustrated with the lack of engagement, on 6 August the family arranged a march to the police station to demand that someone come out to speak to them. Around 300 people gathered: they were there for several hours, and continued to demand a senior officer come to speak to them. Later that night, rioting broke out across Tottenham, which over the next few days spread across London and several other cities in England.

The police apologised for the lack of communication several days later, on 8 August, partially blaming the IPCC: ‘I think both the Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC) and the Metropolitan Police could have managed that family’s needs more effectively’, said Deputy assistant commissioner Stephen Kavanagh. The IPCC responded defensively, saying, ‘I am very clear that their concerns were not about lack of contact or support from the IPCC … It is never the responsibility of the IPCC to deliver a message regarding someone’s death.’ Police stated they had not visited the home of Mark Duggan’s parents to inform them because the family liaison officers at the scene had been told not to by his sister and partner because it would have been too upsetting; family members categorically denied this. Police subsequently offered to meet with the family in person, and eventually did so on 2 September. The Met repeated its apology in February 2012 when a family complaint was upheld by the IPCC.

Misinformation

Meanwhile, misleading information was being fed to the media, resulting in widespread references to a ‘shootout’, and statements that shots had been fired at police by Mark Duggan. At least some of this misinformation appears to have come from the IPCC. Its initial written statement made no reference to any ‘shootout’, but several media reports that did quoted the IPCC as the source, indicating that at least one spokesperson had verbally misled journalists. The Guardian made reference to an ‘apparent exchange of fire’ and a ‘confrontation’. The Telegraph went further, stating that ‘gunman Mark Duggan opened fire’, quoting the IPCC as saying: ‘We understand the officer was shot first before the male was shot’. The Evening Standard said that an IPCC spokesman had stated the suspect had fired first. The Mirror (5 August 2011) and the Independent also both said that it appeared the police officer had been shot first, and quoted the IPCC as the source. (See ‘Mark Duggan killed in shooting incident involving police officer’, Telegraph 4 August 2011; ‘Father dies and policeman hurt in ‘terrifying’ shoot-out’, Evening Standard 5 August 2011).

It wasn’t until several days later that the truth began to seep out, as media outlets reported on 8 August that ballistics examinations had proved that the bullet lodged in the radio was police issue. (For example: ‘Did bullet fired at officers belong to police’, Daily Mail 8 August 2011; ‘Tottenham riot: bullet lodged in officer’s radio at Mark Duggan death “was police issue”‘ Telegraph 8 August 2011; ‘Doubts emerge over Duggan shooting as London burns’, Guardian 8 August 2011). The IPCC refused to comment on the ballistics reports, then issued a statement on 9 August confirming that the bullet had been police issue.

The following week, following pressure from the Guardian, the IPCC issued another statement that conceded it may have ‘inadvertently given misleading information to journalists’ following the shooting. It said:

‘[H]aving reviewed the information the IPCC received and gave out during the very early hours of the unfolding incident, before any documentation had been received, it seems possible that we may have verbally led journalists to believe that shots were exchanged as this was consistent with early information we received that an officer had been shot and taken to hospital. Any reference to an exchange of shots was not correct and did not feature in any of our formal statements, although an officer was taken to hospital after the incident.’

At the pre-inquest hearing in December 2011 the IPCC’s lead investigator, Colin Sparrow, apologised for the misinformation, saying it had been ‘a mistake’.

The impression that is carefully implied in these statements is that the ballistics examinations were able to clear up initial confusion over what had happened. The IPCC suggested that its ‘early information’ was incomplete and this led to wrong inferences being made. However, according to evidence given at the inquest, there had been no confusion on the part of the officers involved. V53 stated ‘I knew Mark Duggan never fired at us… we knew that straight away’. W42, the one hit by the bullet, concurred; Z51, the senior officer on the scene who was responsible for briefing senior officers who were not present, had made notes at 6.30pm stating a bullet had ricocheted, and also vigorously denied conveying misinformation to anyone else. Even if there had been confusion over what had happened, as the Met’s own report into the riots acknowledged: ‘Experience informs both [the police and IPCC] that such early information is often unreliable and should not form the basis for press briefings’.

It is important to see all this in the context of the riots, and the IPCC’s clear awareness of its important political role in the control of information. David Lammy, MP for Tottenham, had asked the IPCC to release information – he stated in the Guardian that very soon after the shooting he had spoken to them about accelerating the ballistics report. When the IPCC did release this information on 9 August, the statement took the opportunity to comment on the riots:

‘I know this is an incredibly difficult time for Mark Duggan’s family, who have made it abundantly clear that they in no way condone the violence that we have all seen…’

Other IPCC statements around this time took a similarly conciliatory tone, ‘I understand the distress … people need answers’ … ’we would request people are patient while we seek to find answers’.

In November 2011, the IPCC took it upon itself to intervene even more directly in the public debate. Another IPCC statement was made that declared a Guardian article ‘misleading, speculative and wholly irresponsible’. The article originally carried the headline and sub-headline: ‘Revealed: man whose shooting triggered riots was not armed; Mark Duggan investigation finds he was not carrying gun when killed in Tottenham’. The Met also complained to the Press Complaints Commission and this was upheld. The Guardian conceded that the headline was misleading as it implied the investigation had concluded, and changed it. In its statement, the IPCC urged the public ‘not to rush to judgment until our investigation is complete and they have the opportunity to see and hear the full evidence themselves.’

Yet, after stating it was inappropriate to comment on the sequence of events before they had been established, the IPCC made a second statement the following week saying the minicab had not been moved from the scene before it should have been, and that they were sure evidence had not been compromised. IPCC chair Len Jackson said:

‘I am taking the highly unusual step of clarifying inaccurate, misleading and more importantly – irresponsible comment that has appeared in recent days in relation to the IPCC investigation into the circumstances surrounding the death of Mark Duggan. I am doing so because, if these inaccuracies continue to gain currency, they risk undermining the integrity of and public confidence in our investigation …’

The context for this later intervention was that Stafford Scott, a long-time campaigner for rights in Tottenham, had written a comment piece in the Guardian about his resignation from the IPCC community reference group. He made a series of damning allegations about what he called a ‘shoddy’ investigation, saying that he wanted no part in it. (Many of Scott’s allegations stand to this day as unanswered questions, although evidence of the IPCC’s mishandling of crucial evidence emerged later that supported some of them – see ‘Agreement or collusion’, below). This engagement of claim and counter-claim at the very least detracted from the IPCC’s important task of establishing the truth about the death.

Meanwhile, police information apparently fed to the media focused on the portrayal of Mark Duggan as a ‘gangster’. The Telegraph quoted unnamed ‘police sources’ as saying that Mark was a ‘well-known gangster’ (‘Man killed in shooting incident involving a police officer, 4 August 2011); and a ‘major player’, ‘heavily involved in criminality’, who ‘lived by the gun’ (‘London riots: Dead man Mark Duggan was a known gangster who lived by the gun’, 8 August 2011). It was also reported he was part of a gang linked to Jamaica’s ‘Yardies’, and that he was associated with ‘Manchester gangsters’ (‘Violence, drugs, a fatal stabbing and a most unlikely martyr’, Daily Mail, 8 August 2011; ‘UK riots: Mark Duggan was nephew of Manchester gangster Desmond Noonan’, Telegraph, 12 August 2011; ‘Duggan and the mobster’, Sun, 12 August 2011).

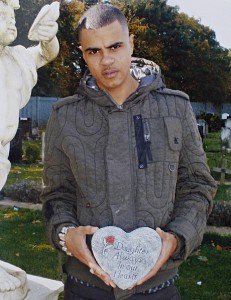

Media coverage painting Mark Duggan as a high-profile and dangerous criminal continued over the next two years. Even the funeral, attended by over a thousand people, was portrayed as a sinister tribute to a gang leader. The funeral procession went from his parent’s home in Tottenham through the  Broadwater Farm estate, where crowds gathered. The Mail featured a picture of mourners stretching their hands out to the coffin under the headline ‘Gangsta salute for a “fallen soldier”’ (10 September 2011), and the Express featured a similar description (10 September 2011) and suggested that they were making ‘gang-land’ salutes (‘Gangsta salute for ‘fallen soldier’ Mark Duggan who sparked riot’, Express, 10 September 2011). In fact, the mourners were responding to a call by Bishop Kwaku Frimpong-Mason for people to ‘stretch [their] hands towards the casket and thank God for Mark’s life as he begins his heavenly journey’. The Mail later printed an apology and slightly amended its article; the Express did not. An image of Mark with a set, unsmiling expression was widely used to accompany articles about his supposed gangster background. This expression was grief – the image had been cropped from a larger photograph of him holding a tribute to his dead daughter at her grave (see both images here).

Broadwater Farm estate, where crowds gathered. The Mail featured a picture of mourners stretching their hands out to the coffin under the headline ‘Gangsta salute for a “fallen soldier”’ (10 September 2011), and the Express featured a similar description (10 September 2011) and suggested that they were making ‘gang-land’ salutes (‘Gangsta salute for ‘fallen soldier’ Mark Duggan who sparked riot’, Express, 10 September 2011). In fact, the mourners were responding to a call by Bishop Kwaku Frimpong-Mason for people to ‘stretch [their] hands towards the casket and thank God for Mark’s life as he begins his heavenly journey’. The Mail later printed an apology and slightly amended its article; the Express did not. An image of Mark with a set, unsmiling expression was widely used to accompany articles about his supposed gangster background. This expression was grief – the image had been cropped from a larger photograph of him holding a tribute to his dead daughter at her grave (see both images here).

The reporting of the Kevin Hutchinson-Foster trial (see Box) had repeated untested claims made by the police about Mark Duggan’s supposed criminality. In the months before the inquest, it was also widely reported that Duggan intended to kill someone with the gun, and that the inquest jury would be considering this. The Telegraph went into particular detail about a ‘tit-for-tat’ murder in revenge for the death of Mark’s cousin Kelvin Easton (‘Revealed: gang rivalry, Mark Duggan and the unavenged murder behind the London riots’, Telegraph, 31 January 2013; See also ‘Jury to decide on ‘gangster’ claim’, BBC News, 31 January 2013). In fact, this question was not put before the jury at all.

But when the jury sat down to consider their questions, the spectre of a violent gangster had become firmly attached to the name of Mark Duggan. The first thing most people heard about him was that he had probably fired at a police officer. The IPCC’s statements did too little, too late to dispel these myths, although it intervened with alacrity when reports started to emerge about an unarmed man being shot. Furthermore, stories of gangland killings may have discouraged witnesses from coming forward. The only civilian witness to actually see the shooting (Witness B) stated he had been reluctant to come forward, not trusting the police but also ‘not wanting to be bothered with’ any gangs.

Inquest in detail

The inquest involved ninety-three witnesses, many of whom were granted anonymity, including most of the police officers. The jury also heard evidence from experts, and non-police witnesses. They were asked to reach conclusions on the surveillance and police operation, the hard stop itself, and the vital questions about whether Mark Duggan was armed when he was shot, and whether he had been killed unlawfully.

One of the central questions was whether or not the firearms officer who fired the fatal shot, known as V53, had actually fired in self-defence, as he had claimed. Another officer (W70) also testified that he had seen Mark Duggan holding a gun. (However, questions were raised about this account: see ‘Agreement or collusion?’ below). None of the other witnesses claimed to have seen a gun in his hand.

V53 described in detail what he called a ‘freeze-frame moment’:

‘As he’s turned to face me, he has an object in his right hand … Mark Duggan is carrying a handgun in his right hand … [Y]ou can make out the shape outline of it, the handle of it, the barrel, you could make out the trigger guard, not visually, but again if you image it going as a L-shape, the sock, there’s like a little bit of give in it, so that’s where the trigger guard would have been.’

Significantly, despite being trained to ‘follow the gun’, none of the police officers said they saw it go flying through the air – on a clear summer’s evening. Expert evidence from the pathologists and Professor Jonathan Clasper (an expert in bioengineering) considered it was not credible that Mark threw the gun after having been shot. Nor could any involuntary movement have accounted for the gun ending up five metres away from where he fell. Nor did the forensic evidence positively support the account that a gun was in Mark Duggan’s hand when V53 fired at him – no gunshot residue was found on the gun or sock, despite Mark Duggan’s clothes and face being covered with it. Neither was there was any forensic evidence to suggest he had ever opened the shoebox or touched the gun or sock.

There were two civilian witnesses to the shooting. One of them, Witness B, said that he saw what was ‘definitely a phone’ in Mark Duggan’s hand. He described seeing him look ‘baffled’, with his hands up in the air as if surrendering, attempting to run, and described seeing the shiny BlackBerry in his right hand. The other civilian witness was the taxi driver. He stated that he did not see Mark Duggan open or close the shoebox during the journey, that he had a good view of him when he left the minicab and he did not see him with anything in his hands, raising his arm or making any threatening movements towards the police.

V53 also claimed that it was the first shot that penetrated Mark Duggan’s chest (the fatal shot). He claimed that Duggan then swung towards him, pointing the gun directly at him, and then the second shot was fired, hitting his bicep. However, expert evidence also raised questions about this aspect of the account. Pathologist Derrick Pounder was of the opinion that V53 had got the order of the shots wrong, and that the non-lethal arm shot had come first, then the fatal shot to the chest. The other pathologist, Simon Poole, maintained it was impossible to tell. However, the pathologists and Professor Jonathan Clasper (the bioengineering expert) agreed that the bullet wounds on the arm suggested that the upper arm would have been rotated towards the body when the arm shot was sustained, rather than pointing outwards towards V53. The experts also agreed that the chest wound demonstrated that Mark Duggan wasn’t in an upright position when he sustained it, but bent forwards. The arm shot wound, on the other hand, was consistent with being upright. Taken together, the lawyers for Mark Duggan’s family suggested, these insights indicated that Mark had been shot in the arm, staggered forward, and was shot in the chest.

The firearms officer claiming to have found the gun, known as R31, said he found it in bushes around five metres from the spot where Mark Duggan was shot dead. Z51, the most senior officer on the scene, also testified to having found the gun. Questions were raised by the family’s legal team about the accounts given by officers about finding the gun, as they did not appear to be consistent with video footage provided by Witness B (known as the ‘BBC footage’). V59 (the firearms team leader) gave several statements and initial evidence at the inquest that stated that he had directed another officer, R31, to look for the firearm. According to V59, R31 returned and told him he’d found it on the grass; subsequently Armed Response Vehicle (ARV) officers had arrived, whom V59 had directed to go and secure the gun. All three ARV officers gave evidence to the same effect. However, this version of events was contradicted by the video evidence, that showed that when the ARV officers arrived and were apparently directed to secure the gun, actually the gun had not yet been found by R31 or by Z51. V59 later was recalled to the court to account for this discrepancy, and claimed he had got the chronology wrong. This would have meant that all three ARV officers’ evidence was also wrong. Leslie Thomas, barrister for the Duggan family, suggested that the gun had been planted, and that was why V59 apparently informed the ARV officers to secure the gun before it had been ‘found’. The Judge noted during his summing up that this was not a simple mistake, but a ‘direct contradiction … [a] stark problem’.

Agreement or collusion?

Police statements raised concerns about the possibility of collusion. The initial statements made by police on the evening of 4 August were very sparse. Full statements were provided several days later on 7 August. Important details did not appear until these later statements – for example, the finding of the gun in the bushes, and the specific number of shots fired. W70’s claim that he saw Mark Duggan raising a gun, a crucial piece of evidence, was not mentioned in his initial report but appeared in his second report. When asked whether this was a deliberate omission during the trial of Hutchinson-Foster, W70 said, ‘I don’t know’.

At the inquest, police officers also described how these longer statements were written over the course of eight hours, as officers sat together in a briefing room at their Leman Street base, with a flip chart at the front of the room. V59 said:

‘[W]e did them in segments […] as you finish your section you then left the room, got a cup of coffee had a comfort break, et cetera. When everybody had finished their section 4, for example, 3 August, we all came back into the room together went through the flip chart process wrote the next section and we all wrote that.’

The officers said that they agreed on details such as ‘times, places, locations, postings, sequence of events’, but denied that they had discussed the actual shooting, or their ‘honestly held beliefs’ about it. When questioned about why they had omitted important information from initial statements, officers said that they were ‘deliberately brief’, and insisted that their statements had been made in line with Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO) guidance. The IPCC did not have a staff member present at the statement writing because there were ‘no resources’ available (according to IPCC deputy senior investigator Colin Sparrow, reported in the Telegraph, 28 September 2012). Following the inquest, Pamela Duggan began court proceedings to judicially review the ACPO guidance; in March 2014 the Court of Appeal decided the challenge could go ahead.

There were further concerns raised about the IPCC’s handling of the investigation. During the Kevin Hutchinson-Foster trial, the IPCC’s Colin Sparrow said that he failed to grasp the significance of the shoebox that contained the gun until a week after the shooting. By the time he was told about the shoebox, he admitted, the minicab had been taken to a police car pound and security seals on the car had been broken. Another IPCC investigator told the court that he discovered the shoebox had been moved within the vehicle, apparently during searches. The minicab had been moved from the scene the day after the shooting and then returned there that day, before being removed for a final time that night – a process which the recovery driver described as ‘unusual’.

The IPCC was also criticised for ignoring the possibility that the gun could have been planted by police officers. Two civilian witnesses, Miss J and her daughter, gave evidence at the inquest that they had seen an officer moving a gun from the minicab in the immediate aftermath of the shooting. But the IPCC, despite being given this evidence early on in its investigation, chose not to explore it further. Even more troubling, according to Stafford Scott, the community advisory group to the IPCC was told that three police officers had given statements saying they had seen an officer throwing a gun away. These police statements were later denied.

Even after the three-month-long inquest, the legal wrangling, and the ongoing attention the case has attracted, the family and the Justice for Mark Duggan campaign face further struggles for the full answers.

Related links

Download this article as a PDF (pdf file, 740kb)

Justice for Mark Duggan Campaign

Very informative and useful. I will be in touch soon.