Activist and poet Sam Berkson examines grassroots resistance to the social and political crisis in Hungary.

On 15 March, a national holiday commemorating the revolution of 1848, some 50,000 people pressed into the rain-soaked square in front of Parliament to listen to speeches, sing together and shout for the removal of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. The teachers, who had led the protest, set out their demands and promised a national one-hour strike, which would be repeated and extended if their demands were not met. They invited the rest of the country to join them.

Putting down the chalk and closing the classrooms for an hour may not seem world-shattering but we must understand it in its context. Liz Fekete’s article in the most recent Race & Class shows the authoritarian path the Hungarian state is treading, colluding with private militia and exploiting racist fears in order to pass a ‘breathtaking’ list of ‘autocratic laws and reforms’ in the creation of a ‘post-Communist mafia-state’.[1] In Hungary, the right even to ballot for a strike can only be obtained with government permission. The teachers’ action took place independently of the union.

Putting down the chalk and closing the classrooms for an hour may not seem world-shattering but we must understand it in its context. Liz Fekete’s article in the most recent Race & Class shows the authoritarian path the Hungarian state is treading, colluding with private militia and exploiting racist fears in order to pass a ‘breathtaking’ list of ‘autocratic laws and reforms’ in the creation of a ‘post-Communist mafia-state’.[1] In Hungary, the right even to ballot for a strike can only be obtained with government permission. The teachers’ action took place independently of the union.

Earlier in the day the Prime Minister had attempted to strike first, denouncing the ‘Bolshevik’ teachers and ‘failed intellectuals’ who were leading this protest. He then continued his belligerent slanders against the mass of dispossessed of the Global South who have been forced to flee to Europe. ‘It is forbidden to say that immigration brings crime and terror to our countries’, said Orbán, apparently unaware of the irony that nobody was stopping him (or other political leaders across Europe) saying exactly that. ‘It is forbidden to say that the arriving masses from other cultures are a threat to our way of life, our culture, our habits and our Christian traditions.’

Orbán’s Fidesz party has practically a two-thirds majority in parliament, yet here were 50,000 people in a country of less than ten million out on the streets protesting his educational reforms, with many demanding his removal. Is this autocratic control, which worries economic and social liberals alike, as unassailable as it appears?

Growing inequality and racial segregation

Spending time in Hungary over the last two years, I have witnessed something of the conditions post regime-change that have allowed such a man to take control of the country. It is not just in civil liberties that Hungarians are suffering. Activist Bálint Misetics noted in a recent interview in Political Critique’s online magazine :

The Hungarian regime is oppressive not only because of its infringement on the independence of the constitutional court, but also because it keeps millions of people in extreme poverty, either intentionally, or with policies that cannot have any outcome other than an increase of poverty and social inequalities. Pushing people into poverty or keeping them poor is a form of oppression.

This poverty is also racialised. Across the country, it is Roma people who are the hardest hit, their situation compounded by racism, both at a state and popular level. They are proportionately over-represented in statistics for extreme poverty, prison or state care, while having less access to education, health care and basic utilities. Many villages and towns are racially segregated with Roma people living on the edges in poor quality housing.

The New War on Immigration (and everyone else)

Whilst the Roma (as well as Jews and LGBT people) have long been the scapegoats for the Hungarian right, Orbán has found a new ‘outsider’ to divert voters’ attention, stepping up the rhetoric against immigration. Inevitably, this has led to the creation of a new armed police unit and greater state surveillance. Orbán wants to use the ‘terror threat’ as an opportunity to change the constitution again to allow for government monitoring of phones, internet and financial transactions.

Fight or Flight?

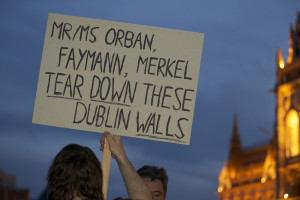

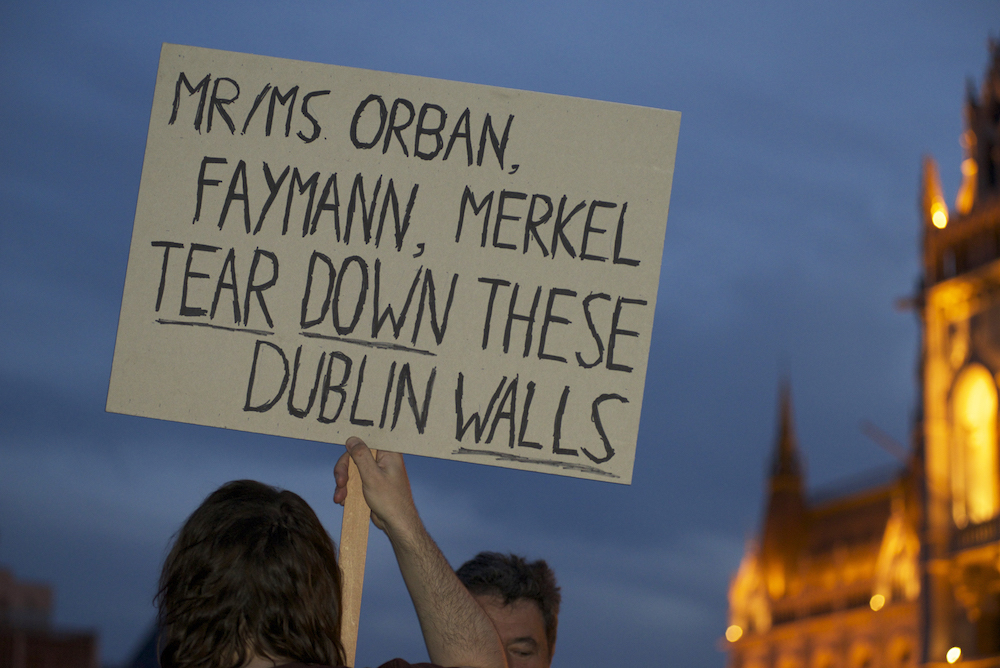

Orbán has built fences along the Serbian and Croatian borders and wants to extend that even to EU neighbours Romania. However, with emigration, especially among the working-age population a big issue, keeping Hungarians in might be more of a challenge than keeping foreigners out.

There are an estimated 350,000 Hungarians living in the UK and large numbers in Germany and Austria too. 39 per cent of Hungarians under 25 say that they imagine their future abroad. Of students, that figure is 45 per cent. These statistics suggest that hope is indeed in short supply. Yet those that remain, or have already returned and are working for social justice are, it seems to me, building something real and tangible.

Over the last few years, there have been brave individuals who have caught the popular imagination. A tax worker resigned and waved a mysterious green folder, threatening to whistle-blow on tax evasion. The United States added to the pressure, announcing that certain unnamed government officials were banned from USA because of corruption. The affair brought the depth and complexity of institutional corruption into the spotlight. Then there was the ‘Black nurse’ who went to work in a black uniform, mourning the death of the health care system. Hundreds of nurses followed in solidarity.

And certain sections of society are showing signs of mobilisation. When the government cut university funding and restricted access, students, widely seen as apolitical, erupted with protests and set up democratic forums, away from the Fidesz dominated student-councils. They did not win on their demands and the movement died out but it had re-awoken a progressive movement.

The civil sector has also been a target for funding cuts but autonomous action has started to rebuild the NGO scene. Over the last few years in Budapest, places have been set up that are independent of government funding and function as social and cultural centres, pubs, and clubs: hosting meetings, debates, film screenings, bands, DJs and the offices of some of the previously dispossessed NGOs.

In Orbán’s second term in office, Budapest activists found direct action. To protest the changes in the constitution, the Fidesz party headquarters were occupied in 2013 and the idea caught on. Homeless action groups occupied a mayor’s office; artists occupied a museum; Green Party activists chained themselves to the front of parliament. For the last three months, activists have been living in abandoned buildings in the City Park, creating what they describe as an ‘open squat’, operating along direct/participatory democracy lines. They have cleaned up the buildings, planted food and regularly host public talks, music, poetry and films. They are resisting the construction of a new ‘museum district’, which they say will involve the destruction of around a thousand trees and create a ‘tourist ghetto’ within Europe’s oldest public park.

State racism has not been unchallenged either. When the government, in May 2015, sent out a ‘national consultation on immigration and terrorism’ to every voter-age citizen, the migrant solidarity group, MigSzol, sent these hugely loaded questionnaires down the Danube as paper boats.

State racism has not been unchallenged either. When the government, in May 2015, sent out a ‘national consultation on immigration and terrorism’ to every voter-age citizen, the migrant solidarity group, MigSzol, sent these hugely loaded questionnaires down the Danube as paper boats.

‘Do you agree with the Hungarian government that instead of spending on immigration they should rather support Hungarian families and future children?’ was one of the questions.

To help sway people’s minds on this consultation, Fidesz put up billboards ostensibly instructing migrants (in Hungarian) ‘not to take Hungarian jobs’ and ‘to respect Hungarian culture’. Individuals everywhere took offence at this propaganda and many were ripped off, painted over or comically defaced. MKKP, The ‘Hungarian Two Tailed Dog Party’, who were not allowed to stand in the 2010 elections, along with the political blog Vastagbőr (Thick Skin) organised to crowd-fund their own fifty, satirical, billboards. Donations, mainly small ones, flooded in and they raised enough for five hundred of the things. They invited people to vote on their favourite text, including: ‘Sorry about our Prime Minister’ and ‘Feel Free to Come to Hungary, We Already Work in England’. Fortunately, the oligarch whose companies owned most of Hungary’s billboards had just fallen out with Orbán, publically and memorably calling him ‘geci’ (sperm or spunk),[2] and the retaliatory billboards went up.

When refugees did arrive in the summer of 2015, official decisions about where and how these temporary visitors were supposed to go changed on a nearly daily basis, leaving thousands of refugees camped out at Budapest’s Keleti train station or in the parks. The state and the big charities provided little assistance and it was civil society who mobilised to provide food, clothes and even ‘secret shelters’ for the ‘guests’. Despite the ‘tough on immigration’ stance of the elected prime minister, the events of last summer showed how this xenophobia is by no means a national characteristic. Budapest’s migrant crisis sparked the creation of new volunteer groups and organisations which are still providing assistance for refugees a year on, both at home and abroad.

Getting your hands dirty: grassroots organising

I volunteered for a couple of days helping renovate an abandoned council house as a home for a couple, who, because they were homeless, have had their children taken into care. The head of the organisation told me how they are fixing up ten such homes this year. ‘It is not much’, says Vera Kovách, ‘but the media attention these projects generate helps raise awareness about what’s going on’. It is also important, she said, that most of the renovation is done by volunteers, getting more people involved in work to counter social inequalities.

This group grew out of AVM (The City is for All), who campaign against unfair housing policies, raise awareness and advocate for homeless people’s rights. They have an activist group, more than half of whom are currently or were formerly homeless themselves.

The School of Public Life is another offshoot from the AVM nursery. At an exhibition’s opening inside a homeless shelter, I listened to people who are vulnerably housed presenting the results of their research projects on the history of Budapest housing movements. Not allowed to have long term residency, guests at the shelter have to queue up each day to sleep on a bench in the communal dormitory.

In a segregated Roma community, in a former mining settlement on the outskirts of Pécs, I visited a social centre, opened with charity money. Members of an NGO were supporting the local working group to build stoves and produce fuel briquettes from sawdust and newspapers to heat the homes of a disconnected community, where gathering firewood is illegal.

Empowerment-based, community-led development is allowing locals to find ways to improve their lives in places that are ravaged by poverty and cheap drugs.

Roma-led NGOs have been active too. Activists mobilised around the decennial census, making sure that, despite corruption (it took 17 months to publish the results) and educational and social marginalisation, the number of Roma people is better represented in the official count. 205,000 Roma were recorded in 2001. Ten years later it was 315,000 – still some way short of what most believe to be the real figure, but a definite step towards getting recognition as equal Hungarian citizens. They have revived Roma Holocaust Day, Roma Day and Roma music festivals. In the Northern town of Miskolc, a Fidesz mayor issued contracts for Roma people to sign, accepting money to leave the city for at least five years, to make way for a football stadium’s car park. A legal rights NGO managed to obtain a ruling against the Miskolc evictions and forced the council to find alternative housing for those they have already made homeless.

In the face of such state policies, when activists help disadvantaged people resist evictions or even when the new Budapest social centres put on Roma bands or play host to the meetings of Roma NGOs, these actions are significant in the joining and mutual strengthening of struggles against racial and social discrimination. After the media coverage of the arrest of AVM activists who were blocking one of many evictions planned in Budapest just before the four-month winter moratorium, the 8th district council decided to extend the protected period.

Hope at last? An Outsider’s View

Now there is a battle for the soul of the country, which thousands of its inhabitants see as a place to leave. Its institutions have been captured by a reckless authoritarian, who is in the business of consolidating his wealth and power, to enrich a little elite of cronies, while condemning thousands to poverty. He has resurrected a fascist-style Christian nationalism, offering to the dispossessed the soggy meal of macho pride and the fairy-tale dream of a Greater Hungary, with himself riding Putin-style as the saviour of a nation.

Spending time among Budapest’s activists over the last two years, I have heard plenty of the famous Hungarian pessimism. Of course, they are right that democracy has been suppressed, inequality deepened and, as elsewhere, there are not enough people taking part in resistance to it. Fekete’s warnings of ‘Orbán’s rightwing extremism’ and his collusion with private militias must be taken seriously. To succeed in maintaining this degraded power game, he will have to move ever deeper into the ridiculous patriarchal posturing and real ethno-violence that characterise fascism. Yet on 15 March, Orbán had to bus in a rent-a-mob of Polish nationalists to swell the numbers of his supporters.

My hope is that, while Fidesz have electoral power, their support is not so deeply rooted. A 2015 survey shows that trust in NGOs is higher than it has ever been and trust in the government at its lowest. Each time a moment arrives that produces resistance it seems to come ‘from nowhere’ and disappear as quickly as it came. Yet, from the student protests to the massive internet tax rebellion and now the teachers’ movement, there is something building behind these ‘spontaneous’ demonstrations. As in other former socialist countries the charge of ‘Communism’ is often enough to discredit opposition and there has been no unifying leftist group able to challenge electorally.

Yet, the everyday organising in communities builds the network of civil society, working together with those who have been marginalised socially or economically – the homeless, the refugees, the Roma – and creating a social scene that is creative, thoughtful and also fun, often led by women or people who identify as LGBT. Of course their efforts may seem like a pittance in the general scheme of things, but it is happening independently of the state and its gains are more deeply felt than its reactionary counterpart. On the anniversary of the Treaty of Trianon, a hundred neo-Nazis stood outside the Romanian embassy in Budapest and demanded back the land taken after the first world war. Nearby, more than ten times that number were celebrating the second day of the ‘Tilos Marathon’, the annual fundraiser for a community radio station that has been broadcasting an eclectic range of music and liberal political opinion since 1991.

It may be that the activist scene will be hampered as key players leave for better salaries in the West. Perhaps the state can work it so that absolute power crushes opposition wherever it appears. Perhaps the alternative movement will be co-opted by EU neoliberal institutions which are also uncomfortable with Fidesz’s concentration of power and wealth. Yet, the internationalism that today’s young people experience, means that it will be difficult to stop people seeing beyond the fenced-in borders of nationalism. Hungary has the added advantage of being a country small enough to foster a coordinated resistance with strong personal links and a few real physical ‘centres’. Each time people take to the streets, the evidence of shared and collective anger becomes increasingly visible.

Whatever comes next, it is clear that the people do not wish to go back either to Soviet-era Socialism or the Christian Conservative / Social Democrat rule that came after. As Misetics puts it:

[W]e must at least ensure, that when this regime falls … it will be obvious to everybody what was wrong with it. It wasn’t only its violation of the principle of separation of powers, or its obscene, systemic corruption, but also that it held millions of people in dependency, income insecurity and poverty. … We must, at the very least, make sure that after a change of regime we will not return to that unjust neo-capitalist swampland which made the emergence of the current anti-democratic regime possible in the first place.

I am a retired academic researcher who carried out research in seven different EU countries on “Racism, Criminal Justice Systems and Social exclusion” for an EU funded programme in 2010. My recommended Hungarian partner turned out to be a young liberal minded regional police officer who obtained access for me to interview prisoners in different prisons. I also had other informants.

There was general consensus that the Roma population was over-represented in the prison population. Since then things can only get worse with the seizure of power by the extreme right wing government as your article above shows. Let us hope that dissident elements can help to bring a more liberal government to power.