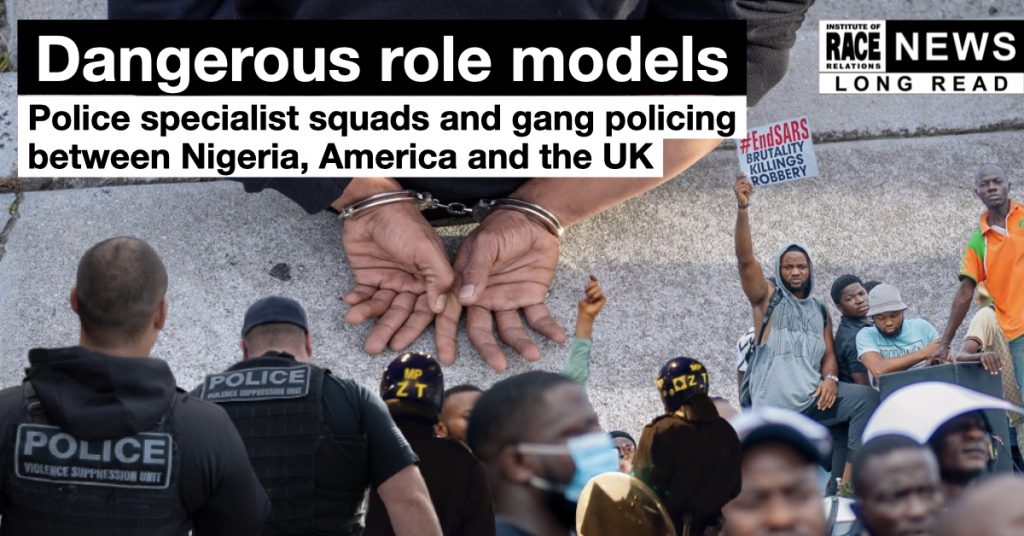

Recently, the Metropolitan police commissioner, defending stop and search, said that some young people were failing to distinguish between the actions of police forces overseas in America and Nigeria and those of police officers here in the UK. But far from young people being confused, as Cressida Dick implies, they are increasingly aware of just how globally interconnected policing is today, and that British police technologies and training continue to play a worrying role in its former colonies, such as Nigeria. There is indeed a connective tissue, both historical and contemporary, that links specialist squads in the UK, Nigeria and the United States. This piece, while ranging over a number of issues, foregrounds the growing controversy around specialist squads in the UK, from the SPG in the 1970s-80s to the TSG to a new specialist squad that was introduced in London at the start of the pandemic. We question whether the introduction of Violence Suppression Units marks a new phase in the Americanisation of British policing with US approaches to gangs being reproduced on British terrain.

SARS and the enduring British influence

When footage allegedly showing the Nigerian police Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) fatally shooting a young Black man emerged on 3 October, a wave of protests ripped through Nigeria sparking a chain reaction against police brutality worldwide, revitalising the Black Lives Matter movement. Though this is the first time that SARS has attracted attention on such a large scale, Nigerians have been speaking out against the violence of the squad ever since its creation in 1992 and protesting in earnest since around 2017, whilst organisations such as Amnesty International have long been raising the alarm on the numerous human rights violations committed by the squad – including torture, extrajudicial killings, unlawful detentions and extortions.

In the aftermath of the #EndSARS protests that ensued after 3 October 2020, and which intensified as Nigerian security forces shot dead protesters according to witnesses and Amnesty International, on 29 October it transpired that the UK government had provided training and equipment to SARS between 2016–2020. In response to this revelation, Amnesty International’s UK foreign affairs adviser said, ‘It’s alarming that UK government funds have apparently been used to train and equip the notorious SARS police unit that for years has been operating with systematic torture. Whether the training has included human rights or not, such funding clearly warrants independent investigation, not least because serious abuses persist.’ As facts pertaining to the UK’s involvement in SARS continue to emerge, with the Guardian recently disclosing that the Nigerian police have been authorised to purchase £127m-worth of UK registered arms since 2008, the Labour Party has demanded that the UK government consider suspending the funding and training of Nigerian policing and military and that it carries out ‘independent investigations into the allegations against Sars units, as well as military, security and policing forces responsible for attacks on protesters’.

Chi Onwurah, who leads the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Africa, has emphasised the UK’s responsibility in launching an investigation, citing the ‘enduring influence and consequences of the colonial period on Nigerian institutions, including the police’. As Professor of History at Vanderbilt University Moses Ochonu, has explained, contemporary Nigerian policing is entrenched in British colonial policing which served to ‘dominate space, intimidate communities, and mete out exemplary punishments to serve as deterrents’ through ‘brute force’. And because the postcolonial Nigerian police force never underwent processes of reform or decolonisation following independence in 1960, colonial-style policing seeped into the Nigerian present unchallenged, explaining the contemporary violence of SARS.

Problems at home: from the SPG and TSG …

As evermore scrutiny turns to the UK’s involvement in the human rights violations of the SARS specialist squad, it becomes equally important to pay close attention to the UK’s own police specialist squads, which have also been tainted by accusations of excessive violence, harassment and impunity. For example, the Metropolitan Police’s Special Patrol Group (SPG), a centrally-based mobile force equipped with riot gear and firearms established in 1965 and named after the SPG counter-terrorism unit of the Northern Irish police force, quickly gained a reputation as one of the most infamous specialist squads in British history. During its years in operation, the SPG would aggressively orchestrate raids and mass stop and search campaigns in primarily Black communities, fortifying its notoriety which peaked in 1979 when SPG officers ‘almost certainly’ killed New Zealand-born anti-racist teacher Blair Peach by striking him with a truncheon. Following this event, public hostility towards the SPG escalated, with Ken Gill of the Trades Union Congress proclaiming to the 15,000 audience at Peach’s funeral that the SPG must be disbanded, to the extent that it (and the Instant Response Units which supplemented its work) was dissolved in 1987.

In 1987, the SPG was replaced by another specialist squad which remains in operation today – the Territorial Support Group (TSG). The TSG, which has the ostensible purpose of policing public disorder through marked police vans, has seemingly carried on the legacy of its predecessors by operating in ‘hotspots’, implied as those with serious levels of gang-related violence, i.e., in Black and minority ethnic communities. As such, since its inception, the TSG has also, like the SPG, been plagued by accounts of violent and racist behaviour. Within the past nine months, the TSG has controversially stopped and handcuffed Black British athletes Bianca Williams and Ricardo dos Santos; tasered 23-year-old Black man Jordan Walker-Brown leaving him paralysed; and been implicated in claims of assault of a Black female student. This is not new conduct, and, of greater gravity, Ian Tomlinson died after being struck by a baton by a TSG officer in 2009 in ways that echoed Blair Peach’s death, and 17-year-old Jack Susianta drowned after jumping into a river in East London as TSG officers chased him in 2015.

Amongst the Black community in particular, TSG vans have become symbols of police violence and racism. According to Jordan Walker-Brown, on 4 May 2020 TSG officers spotted him and got out of their van to pursue him, and Jordan, who had fresh in his mind the memory from the previous day when he says he had been held and mistreated in a TSG van, ran from the TSG officers – jumping over a wall to escape. As he jumped, the officers tasered him, meaning that he fell from a great height leaving him paralysed. Elaborating on why he ran from the TSG he said, ‘I know, from my own personal experience as a young black man, that I always have to be very careful of being alone with police officers in a police van.’ The fear of the TSG amongst the Black community articulated by Jordan is continually referenced in London-based drill and road rap, Black musical genres and subcultures born out of South London’s inner-city neighbourhoods which capture the realities of violence and deprivation at the margins of the city. To illustrate, ‘Monkey’ and ‘LD’ of Brixton drill collective ’67’ allude to the TSG’s constant ominous presence by rapping about ‘runnin’’ and ‘ducking’ ‘from the undies and TSG vans’[i]; whilst Peckham drill group Zone 2 flip the script by describing their perceptions of the specialist squad: ‘Most hated gang, TSG van’.

… to VSUs

In the midst of the first coronavirus lockdown, Metropolitan Police Commissioner Cressida Dick announced the launch of a new specialist squad named Violence Suppression Units (VSUs), which were to be introduced as part of a plan to ‘capitalise’ on decreased crime levels during the lockdown period. Cressida Dick stated that the establishment of VSUs, which were officially operational on 4 May 2020, would fortify the MPS’s ‘commitment to drive out crime within neighbourhoods’ by deploying ‘more officers on the beat’. Specifically, the 12 Violence Suppression Units across London, comprised of 620 officers in total, engage in intelligence-gathering, raids, weapon sweeps and stop-and-search practices which aim to recover weapons. They police 250 microbeats: areas ‘where gangs, drugs and violence have flourished’; and thus are framed as having the primary purpose of combatting gang violence. And because the government, the police and the media have, over decades, consistently constructed the aforementioned matters of gangs, drug-trafficking and violence as racialised issues emanating from and particular to the Black community, VSUs, like the TSG and SPG that preceded it, operate on logics of spatialised racial profiling.

Consequently, in ITV video footage accompanying an VSU, we see a VSU van pulling up to an estate in Barking, East London, and officers jumping out to question and seemingly harass the Black men hanging out there – who are assumed to be potential criminals because of their race and locale. Unable to prove any wrongdoings, the VSU leave the scene. Cut to Channel 4’s excursion with the specialist squad, and we see a VSU carry out a stop on two young, Black Muslim men in a car – the result of mistaken identity. Despite the error, the police proceed to handcuff the two men and search the car for 10 minutes. They find nothing. Perhaps of greater concern, in one of the following scenes, a VSU targets a South London estate and handcuffs a 17-year-old child of BME background in care who has been reported as missing. Once again, no offences are evident. Furthermore, despite grand claims of making the streets safer through stops and searches, a power proven to produce racist outcomes and to have at best a marginal impact on crime levels, all that is found during these expeditions are cannabis – something that Dr Adam Elliott-Cooper notes is typical of such beats – and cash. That these events occur in the knowing presence of journalists and cameras at the height of 2020 Black Lives Matter protests sets a dangerous precedent regarding the future of VSU operations.

Violence Suppression Units: American past lives

Interestingly, specialist squads of the same name – Violence Suppression Units (VSUs) – have existed in California for many years prior to their emergence in the UK. The Merced Police Department (PD) established a Gang VSU in 1994, the Salinas PD founded its VSU in 1995 and earliest mentions of Concord PD’s VSU date back to 2015, while Chico PD just formed a VSU in 2020. While the Salinas PD VSU developed out of its ‘Gang Task Force’, the Chico PD VSU appears to be a remodelling of its prior ‘Gang Violence Unit’, demonstrating the strongly explicit anti-gang focus of Californian VSUs. As follows, the Californian VSUs present themselves as Units trained in gang structure and criminal activities that focus their operations around the suppression of gangs via ‘aggressive patrol strategies’. These strategies generally comprise of surveillance and intelligence; searches and traffic stops; raids and search warrants; and engagement with informers. Considering that the aggressive patrol strategies of Californian VSUs very much align with the strategies of VSUs across the pond in London, epitomised by Metropolitan Police Sergeant Looker saying that VSUs symbolise ‘a return to the old-school principles of pounding the pavement’ – and that the Units in both countries share the same name – it would be remiss not to ask the following question: Are the Metropolitan Police Service’s VSUs modelled on Californian VSUs?

The Americanisation of British gang policing?

Though we cannot definitively prove whether or not the MPS’s VSUs are indeed modelled after those of the same name in California, we can contextualise the emergence of the MPS’s VSUs in the broader landscape of British and American gang policing in order to explore the possibility of American gang policing being reproduced on British terrain. To this effect, it is important to note that the main police anti-gang initiatives that currently exist in the UK previously existed in the US prior to the early 2000s. To illustrate, in the US, police specialist gang squads proliferated tremendously during the 1980s; the first gang-databases such as California’s CalGang appeared in 1997 with GangNET (the name for the technology outside of California) being established afterwards; gang injunctions, court orders preventing suspected-gang members from participating in certain activities, arose through the joint efforts of the Los Angeles PD and the Los Angeles city attorney in 1982; and lastly, facial recognition technology (and its use in conjunction with gang-databases) in law enforcement has been in use since the 2000s.

In contrast, the configuration of British gang policing emerged a lot later than it did in the US, as it mostly developed in direct response to the 2011 riots following the police shooting dead of Mark Duggan, in which those involved were conflated with ‘gangs’. In the days succeeding the riots, then Prime Minister David Cameron professed a ‘concerted, all-out war on gangs and gang culture’, which resulted in the establishment of explicit anti-gang strategies, including the development of gang-focussed specialist squads. For example, within six months of Cameron’s proclamation, the MPS’s Operation Trident was expanded to form the specialist squad ‘Trident Gang Crime Command’ and a UK version of a gang-database, The Gangs Matrix, was brought into operation. In addition to these efforts, the UK widened the scope of existing gang injunctions (founded in January 2011 before the riots) which had previously only applied to adults, to include 14-17-year-olds from January 2012. Furthermore, most recently, from 2016 – 2019 the Metropolitan police conducted facial recognition trials in concurrence with watchlists (a list of individuals of interest to the MPS attached to facial images and metadata) and deployed it as a standard method of policing in 2020. In this context, the advent of Violence Suppression Units not only potentially signifies the latest outcome of the SPG to TSG development arc, but part of an ever-expanding landscape of British gang-policing which appears to be modelled on the original American version.

Evidently, much of the aforementioned American gang-policing methods originate in California, the reason for this being that gang policing in California is arguably the most pronounced out of any state in the United States. This is due to the state’s (Los Angeles is colloquially referred to as ‘Gang Capital’ of America) strong association to gangs such as the transnational Mara Salvatrucha of Salvadoran-American roots and the 18th Street Gang of Mexican-American origins as well as gangs like the Crips and the Bloods of primarily African American composition. If on one end of the certainty spectrum, we are to tentatively suggest that the UK has constructed its gang policing based on elements of the Californian model, on the other end of the spectrum, we have clear examples of when the UK has looked to American gang policing – albeit at the opposite end of the country – in New York. A case in point was in 2018, when Senior MPS officers and representatives from City Hall travelled to New York to observe how the New York Police Department tackles gang violence as former New York (and Los Angeles) police chief Bill Bratton said that the Met and the NYPD could learn from each other in their fight against gangs. And before that, in the days following the 2011 riots, David Cameron tried to appoint as new Metropolitan Police Commissioner Bill Bratton, a controversial figure and staunch proponent of heavy-handed policing who helped influence the police department to move further into Black and Latino neighbourhoods through ‘broken windows’ policing. In fact, Bratton is so esteemed in the UK that in 2009 he received a CBE (Commander of the Order of the British Empire) for his work to ‘promote cooperation between US and UK police’, during which he was praised for his efforts to ‘exchange ideas and best practices’ between the countries ‘on every aspect of the policing agenda – from terrorism and radicalisation, to crime reduction, to the forensic use of DNA, to police information systems.’

So, as we continue to support Nigeria’s repressive policing methods, which emerged from our own colonial past, at the same time, it appears that American models are imported to the UK, highlighting how states assist and learn from each other as they seek to develop ever more authoritarian modes of policing.

A dangerous role model

Theoretically, America would be a dangerous country to elect as a role model for gang policing for multiple reasons. For instance, American gang policing methods have been so heavily critiqued for their: inaccurate and ambiguous definition of gangs; intrinsic racism as they disproportionately target Black and Latino communities; excessively violent and harassing nature; and their inefficacy in decreasing gang violence, to the extent that many American gang policing methods have either been suspended or terminated. In particular, at the height of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020, Californian police halted use of Los Angeles PD records in the CalGang database and Los Angeles PD were suspended from using the database and inputting entries, and two years ago a federal judge banned Los Angeles PD from enforcing nearly all gang injunctions. Furthermore, facial recognition technology and its use in policing has been banned in many Californian cities such as in San Francisco, Oakland, and Santa Cruz as well as in Boston, Massachusetts and Portland, Oregon. In addition to accusations of their especially violent and racist ways, specialist squads specifically have been criticised for their distinct lack of accountability as they are more autonomous in nature. The inherently violent and unaccountable nature of specialist squads has led to the disbandment of many specialist squads tackling gang violence such as the New York PD anti-crime unit and the Chicago PD drug and gang unit. And the Rampart scandal, in which ‘more than 70 officers were implicated in misconduct, including unprovoked beatings and shootings, planting and covering up evidence, stealing and dealing drugs, and perjury’ in the Community Resources Against Street Hoodlums (CRASH) anti-gang unit of Los Angeles PD’s Rampart Division in the late 1990s, resulted in the disbandment of the specialized squad in 2000. Despite gang policing in the UK being a relatively recent phenomenon, it has already been subject to many of these same criticisms, alerting many community and rights organisations about the treacherous path that we may have already embarked upon.

Of great cause for concern, gang policing in the States often operates in conjunction with immigration policing, meaning that communities of colour have become doubly targeted by nativist state policies. This has a long tradition in America, as during the 1990s the state repeatedly implemented policies to broaden the criteria for which one could be deported, in part by incorporating crimes of an assumed gang nature. For example, while The Crime Control Act of 1990 included ‘crime[s] of violence and the ‘illicit trafficking in any controlled substance’ as reasons for deportation, the 1990 Immigration Act listed the ‘attempt to commit a drug crime’ as a deportable offence. These policies, accompanied by the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 which further expanded crimes for which one could be deported, resulted in the deportation of 46,000 convicted people to Central America between 1998 – 2005. Furthermore, the notorious ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) encompasses a National Gang Unit to tackle transnational criminal gangs through intelligence and the disruption of gang activities, and beyond this, ICE introduced ‘Operation Community Shield’ in 2005, a multi-agency law enforcement initiative that investigates, prosecutes and removes alleged gang members from ‘neighbourhoods and ultimately from the United States’. As the New York Immigration Coalition and CUNY School of Law summarise, law enforcement and immigration authorities ‘have gone beyond the publicized gang sweeps and are in fact using gang allegations broadly in the immigration removal and adjudications process’.

In the UK, the convergence of immigration and gang policing is in its (comparatively) early stages. It is most clearly expressed through Operation Nexus, as it involves various UK police forces[ii] working together with Home Office Immigration Enforcement to target ‘‘high harm’ foreign national offenders, including gang members’ for deportation. But with Priti Patel recently pledging to reduce jail time of foreign criminals needed for deportation and to make deportation flights to Jamaica a ‘regular drumbeat’, might we see an acceleration in the development of collaborative immigration and gang policing ventures?

And so, returning to the Metropolitan Police Commissioner’s comments that some young people ‘won’t necessarily distinguish between what’s happened in America, or even in Nigeria and here’, I would say that she’s right, we young people, we’re catching on. Historically and geographically, we’re connecting the dots.

I learnt a lot reading this analysis. The connection that is being made across the globe – Nigeria, France, Britain and US is very revealing. It demonstrates how state security services are sharing strategies for controlling communities using tropes such as gang, violence, extremism etc. Britain has been involved in training the police in the post colonial countries such as Nigeria, Kenya etc. The analysis needs to be widely discussed and communities need to come together to resist these methods.