Two challenging new books to inspire young people in these grim, austere and unjust times.

The description of William Cuffay (1788-1870), his father an ex-slave from St Kitts, his mother a Kentish woman, from the November 1849 ‘Convict Description List’ after his arrival from transportation from Wakefield Prison to Hobart in Tasmania, is lucidly set down in Martin Hoyles’ compelling biography of his life and times:

‘He was described as aged 61, four feet eleven inches in height, Church of England, married with no children. He had one sister, named Juliana, and he could both read and write. His native place was Chatham and he was a tailor by trade. He had a dark complexion, medium head, black thin hair, grey whiskers, narrow visage, high forehead, brown eyebrows, hazel eyes, broad nose, large mouth and medium chin. He was rather bald and his shin bones and spine were deformed.’

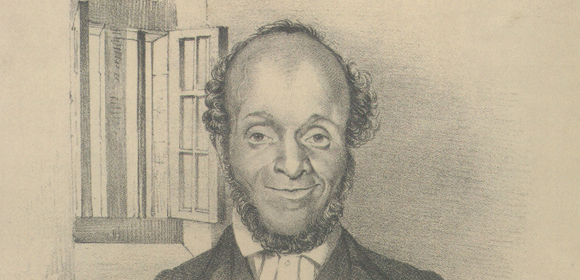

Clear, naked and real; like the contemporary drawing of Cuffay in his cell – smiling, besuited, one arm tucked in his waistcoat – which illustrates the cover of Hoyles’ pioneering book, and a part of the nineteenth-century world of rebellion within which the timeless Cuffay was an integral element.

Migrating from Chatham’s grim dockyards, by 1834 Cuffay was blacklisted after his involvement in the bitter London tailors’ strike. From 1839, he was a wholehearted and relentless Chartist militant, achieving a national leadership position within the first mass working-class movement in world history, advocating a direct march to Parliament at the epochal huge demonstration for the People’s Charter on Kennington Common in April 1848. Following Parliament’s rejection of the Charter, his part in a clandestine revolutionary grouping which advocated a London uprising, caused him to be arrested in September 1848, convicted of ‘levying war on the Queen’ and sentenced to transportation to Tasmania, where as a ‘ticket of leave’ and later a freed convict, well into his 60s, he continued organising working people in the Antipodes for the rest of his life.

A signal hero, virtually ignored by establishment British historians and nowhere to be found within ‘national curriculum’ perspectives of history. Thus, Hoyles’ book is a very welcome tome, which should find a rightful place within every British (and Australian) school library and nineteenth-century history course. For Hoyles’ approach is not to generate a pin-pricked focus on the detail of just one remarkable man’s eventful life – although we learn much about Cuffay’s character and astonishing experiences within its pages. It is his lifetime which the author stresses, giving his readers a broad societal view of the wholistic life in which his protagonist played such a vital part in both England and Tasmania, helped by the multiplicity of illustrations of those mercilessly hard and struggling years and quotations from the protest-filled poetry and prose of the era.

Do our school students learn, for example, that a quarter of the British Royal Navy was black by the end of the Napoleonic wars, or that the great African-American anti-slave campaigner Frederick Douglass referred to himself as a Chartist and toured British cities speaking on Chartist platforms, inspiring British working people with his stirring oratory and spirituals a century before Paul Robeson, drawing powerful comparisons between the plight of the US slaves and the ‘ancient Anglo-Saxon slaves of England’?

A gift for anyone is this fine book: a retired teacher like myself learned as much from it as a teenaged school student, and it took me back in my historical imagination, back to Cuffay’s brave and brilliant life, and all the tribulations that he and his comrades faced and struggled against. An exemplar indeed for our own grim, austere and unjust times.

Another potent read for school students is Bali Rai’s short, accessible and arresting novella, What’s Your Problem?, which, in very direct and bare-worded language, pulls its readers into the lives of an Asian family who move from a more secure Nottingham inner-city neighbourhood to a Midland village location, where the father has bought a newsagent shop. Their experiences are seen through the eyes and mind of the teenage son, Jaspal, who encounters the extremes of youthful life. Loyalty, particularly from the girls he befriends at his new rural school, and the violent gang racism from some of the boys, particularly those infected by the ideas of a fascist organisation called ‘the Brotherhood of the White Fist’, which spread out into the parochial hostility of the village.

The author wastes no words. From the first chapter the reader is hurled headlong into the family’s life and predicament, and the pressure continues throughout the novella’s eighty pages until the tragic consequences of its ending, which reflect the reality of many real now-times news stories. This is a reading experience that will engage the consciousnesses of thousands of school readers, and in particular English teachers need to buy class sets so that the book and its themes are read and discussed in classrooms all over Britain. For What’s Your Problem? opens up vital social questions which need to be at the creative head and heart of all our schools.