A recent publication on policing from rightwing think-tank Civitas extends its attack on anti-racism into a ‘white victimhood’ thesis.

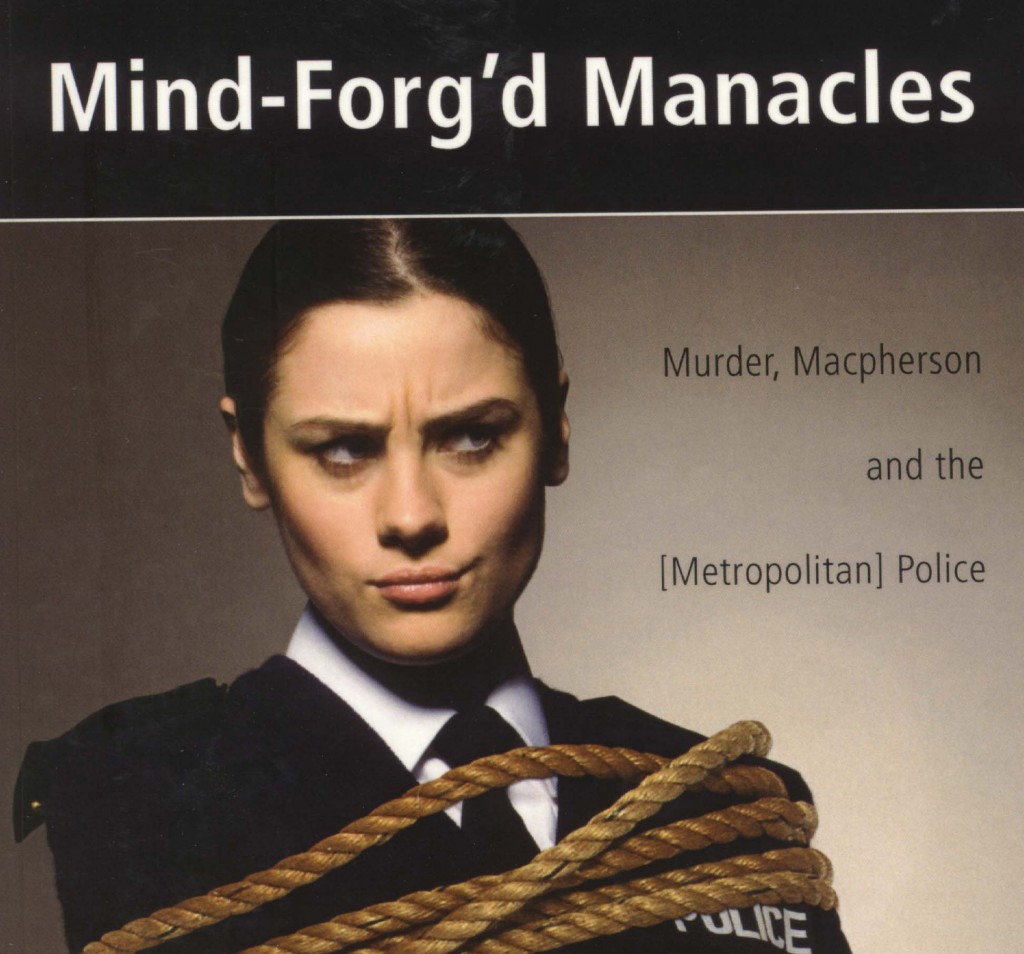

Civitas’ latest pamphlet, Mind-Forg’d Manacles by ex-Labour Councillor Jon Gower Davies, is an attempt to bury once and for all Macpherson’s finding of institutional racism in the Metropolitan Police Service. It argues that this finding has ‘bogged down the police with unnecessary and counter-productive bureaucratic demands’, creating an ‘Orwellian central control’ which prevents the police from investigating the crimes of BME perpetrators – ‘ethnics’ in Davies’ cosmopolitan phrasing.[1] In a paranoid revision of recent British history, it details a process whereby Britain’s white majority was usurped. Hounded towards a frenzy of self-flagellation by the press, this ‘collective national confessional’ was a forced admission of guilt. In the eyes of the author, every white man and woman was declared guilty of personal racism, which implied a shift in the UK’s social order away from ‘the over-riding legitimacy of majority rule’, ceding power to new BME ‘elites’. After beating this confession from the public, a state-sponsored anti-racist elect sought to enforce redress.

In order to come to this conclusion, Davies misinterprets institutional racism as ‘a plague infecting all and sundry – though, critically, white people’. The history of BME empowerment in the late twentieth century that Davies documents is a picture of a power-grab by demographics. ‘Ethnic minority communities’ were in a position of ‘semi-isolat[ion]’ and ‘relative communal strength’, and could so ‘negotiate better and better “terms of settlement”’. Davies implies that these isolated communities, left to their own devices, were allowed too much bargaining power over a well-meaning but overly sensitive liberal establishment. This, coupled with the ‘highly centralized nature of the British state’, allowed the interests of BME communities to be disproportionately represented in British institutions over and above the interests of the white majority. The stage was set for the post-Macpherson development of a two-tier justice system, according to which white people’s guilt is assumed and black people’s innocence presumed; ‘being “sensitive” to minorities mean[s] being “sensitive” to their virtues but Nelson-blind to their vices’.

Britain’s white majority, according to the author, has been failed by reverse discrimination. An institutionally anti-white criminal justice system and a police force on its knees together ‘den[y] legitimacy to mainstream British culture’, creating new ‘paths of social control’ that, through neglect or malice, have sacrificed Britain’s white population in the name of ‘a new orthodoxy’.

For Davies, New Labour tied the police down with rigid regulation – they ‘propelled, cajoled and bullied the police into the Macpherson world’. In order to press home the necessity of a more flexible method of policing communities, Davies presents us with a racial typology that harks back to the colonial era. But instead of overt biological types, he resorts to culture to explain behaviours and therefore necessary policing. Criminality is determined by foreign cultural mores and imported wholesale to all-too-liberal Britain. He studies the ‘black or Asian minorities [who] have their own distinctive, statistically significant, criminal profiles’: ‘I refer to ordinary crimes such as assault, knifings, theft, receiving, drugs, as well as to more exotic ones such as coerced marriage, “honour” killing, and terror’. Davies attempts to justify the disproportionate use of stop and search against black people, on the grounds that ‘Jamaica has the highest murder rate in the world’. This, according to the pamphlet, is understandable enough; one would hardly expect anything else from immigrants, ‘with few of them, legal or illegal or semi-legal, coming from parts of the world habituated to “policing by consent” by unarmed policemen and women.’ The suggestion in much of his writing is that BME communities need to be policed with a greater degree of force than other communities. The shackles of an anti-racist agenda have taken away that possibility, putting ‘indigenous’ Britons at risk.

This argument rests on Davies’ assertion that certain races are culturally more predisposed to certain crimes. So, to back up his claims that black youths need to be policed more robustly, he presents us with ‘statistics’: over half of knife crime perpetrators are black, while ‘most victims in reported knife crimes [are] white’. Davies, with academic rigour, found these statistics, originally from a ‘confidential’ source at Scotland Yard, in the Daily Mail (which has been successfully ruled against by the Press Complaints Comission for inaccurate and distorted reporting three times more often than any other national newspaper).[2]

While Davies insists that Macpherson tied one arm behind each police officer’s back, the reality is that the police force prospered under New Labour. With more police officers, more funding and more powers, the prison population of England and Wales almost doubled between 1993 and 2010, from 44,500 to 85,000,[3] hardly the work of timid, manacled police force, bogged down in box-checking and form-filling post-Macpherson. He advocates a more flexible police force, and applauds Theresa May’s proposals for reform as the end of the era of state interference, quoting police sources that welcome her plans as the end of ‘endless navel gazing’. In June 2010, May announced that police were to be freed from ‘top-down’ central control, adding that although some officers may ‘like the comfort of knowing they have ticked boxes … targets hinder the fight against crime’.

Davies wants both a strengthened police force and a more ‘flexible’ one, and he looks to May to provide it. The irony is that in May’s vernacular, flexibility is a euphemism for a 20 per cent funding cut, which, of course, the police don’t like.[4] Davies’ version of flexibility is freedom from procedures of accountability (so many manacles), so as to police BME communities more firmly. The reality is that despite these supposedly hampering accountability procedures, Black people are still subject to stop and search at seven times the rate of white people, while Asians are made to suffer it at double the rate.[5] For Davies though, even the thin veneer of accountable policing is a compromise.

There are lies, then there are damn lies, then there god damn lies and then there are statistics.