Below we publish an edited version of the speech given by Suresh Grover, Director of The Monitoring Group and former coordinator of the Stephen Lawrence Family Campaign, at the parliamentary meeting ‘Police Corruption and racism: an endless legacy‘ on 23 June 2014.

Why do the police treat anti-racist and black justice campaigns as though they are subversive asks Suresh Grover.

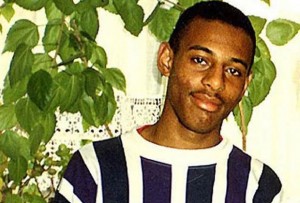

The police have been spying on black justice campaigns for decades. Thanks to the revelations of undercover police officer turned whistleblower Peter Francis (pseudonym Peter Black ), we now know that the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) was spying on the Stephen Lawrence campaign.[1]

At a packed parliamentary meeting convened by The Monitoring Group, campaigners discussed the implications of the first Ellison review (into police corruption and undercover policing in the Stephen Lawrence case),[2] Operation Herne (the police’s internal review into the SDS) and began to discuss ways to respond to the Home Secretary Theresa May’s announcement of a new judge-led public inquiry into undercover policing. Its terms of reference are yet to be set.

‘The first point we need to acknowledge is that the new judge-led inquiry announced by Theresa May, is an inquiry into the last inquiry – and what this indicates is that we failed somewhere down the line. It’s an inquiry that arises from the fact that significant material was withheld from Macpherson,[3] withheld from the Lawrence family, as well as from black communities.

‘The first point we need to acknowledge is that the new judge-led inquiry announced by Theresa May, is an inquiry into the last inquiry – and what this indicates is that we failed somewhere down the line. It’s an inquiry that arises from the fact that significant material was withheld from Macpherson,[3] withheld from the Lawrence family, as well as from black communities.

Preparing for the inquiry

So should we be cynical? If we look back we will remember that we faced the exact same cynicism at the time of the Macpherson inquiry. But even so, we prepared. Campaigners, with the family and with the lawyers did everything in their power to ensure that whatever came out of the Macpherson inquiry would come out as openly and transparently as possible. So the first point is that despite the circumstances of this new inquiry, I don’t think we should be cynical. I think this inquiry could be as pivotal as the last one, in terms of what we can gain, and how we can move forward. So rather than be cynical, I’m going to argue that what we in the black justice campaigns (as well as the peaceful protest movements) need to do is to prepare ourselves properly. To ensure that in this inquiry all the relevant material comes out into the open because what we need is a real accountability mechanism that we can trust. And it’s important that we leave no stone unturned.

Supporting victims of racial violence does not equal extremism

The logistics of this new inquiry, as I understand it, will be difficult. It will focus on the role of the SDS. The SDS was formed in 1968, so the inquiry will be looking at operations from 1968 until 2008 – and countless number of people connected to many different campaigns and issues have been spied upon during that long period. But what at the moment is unknown, and what I want to focus on today, is the amount of intrusion and spying that has taken place in black communities during those years. In the past, we had intimations that this was happening, but we didn’t pay much attention because at that time all our energies were concentrated on supporting the victims of racial violence, and trying to achieve police accountability and justice for them. One example I can give in hindsight, comes from 1989. At that time I was the coordinator of the Southall Monitoring Group (SMG) and also coordinating the justice campaign for Blair Peach. (Blair was the teacher who was killed by the Special Patrol Group on 23 April 1979 during an anti-fascist counter-mobilisation of the mass invasion of Southall by the National Front.) The journalist David Rose wrote an article in the Guardian on 13 December 1989, which confirmed what Peter Francis had told Guardian journalists about spying on the black community. I went back and retrieved that article. It states, that in 1987, the SMG were the subject of a report written by Ealing police intelligence officer, PC J.E. Black which, quoting a disaffected Labour councillor on the controlling Labour group, describes SMG as a ‘political cell’ set up by the Greater London Council (GLC) to follow an agenda while purporting to be a community organisation. It further describes SMG’s efforts to make links with militant left-wing trade unionists, as an active attempt to expand its influence over the whole of west London. It concludes that while the group ‘can be expected to continue its attempts to undermine the police, they are unlikely to be successful except in conditions of widespread disorder, general strike, etc. when they might have a potential for more widespread destabilisation’.

In one way, it seems funny! This is what it said about a small group of people – fifteen, at the most – working in Southall in 1989! But the language of the police report gets worse. It explicitly links our work for racial justice with so-called ‘extremism’. A Chief Superintendent at Hounslow police station, Alastair McLean, is cited. Now at that time, Chief Superintendent McLean waged a relentless battle with the SMG, simply because we were questioning the police’s failure to support the victims of skinhead violence on the Sparrow Farm estate. Our support for this beleaguered family is taken by McLean as evidence that SMG is an extremist organisation which manipulates racial violence on behalf of a faction of left-wing councillors on the Labour-controlled town council. So just by supporting the victims of racial violence, and being funded by the GLC, we stood accused of being manipulated by the GLC and the Labour Party with McLean stating that ‘any Council which actively engenders support for such an organisation is in breach of the trust and duty placed in them by the electorate’.

Not content with political interference locally, here’s what McLean then tells a meeting of the Police Superintendents’ Association, as cited in the same article by David Rose. He says that he was disgusted by the Met’s failure to hit back against comments made by Bernie Grant MP to the effect that the Tottenham Divisional Chief was incompetent. ‘I am now prepared to act’, he says ‘with the same political cunning as any politician’.

Managing the Macpherson inquiry via spying on the Lawrence campaign

So let’s move on to some more recent examples, that give more insights into the spying on black communities by the police. Let me paraphrase some of the revelations that are included both in the initial Ellison review and the police’s internal report Operation Herne.

So let’s move on to some more recent examples, that give more insights into the spying on black communities by the police. Let me paraphrase some of the revelations that are included both in the initial Ellison review and the police’s internal report Operation Herne.

The Herne Review is an internal police investigation conducted on behalf of the Metropolitan police by Derbyshire Chief Constable Mark Creedon. The Herne report cites officer A’s claim in an Observer article of March 2010 that the SDS targeted black campaigns that had been formed in response to deaths in police custody, police shootings or following serious assaults by the police. Officer A states that once the SDS infiltrated an organisation it was effectively finished. This is a serious revelation. Undercover officers are not only ‘reporting’ on campaigns but undermining and sabotaging them from the outset. But what conclusions does Creedon draw? He says that there is no evidence to support the view that there have been systematic incursions into the black communities despite the claims made by officer A.

Now contrast this to the entirely different conclusions made by Mark Ellison QC. Ellison finds that, at the time of Stephen Lawrence’s murder, the SDS operatives were tasked to spy on African-Caribbean groups in order to log community concerns. Who governs this operation is not known, because vital documents that would have recorded the details have not been retained. This is one of the reasons why Ellison recommends a public inquiry. So what we know now is that from the time of Stephen’s murder in 1993, there was specific tasking of spies to go into the African-Caribbean community. From there on, Ellison cites evidence that the police singled out Lambeth, specifically Brixton. There were no concerns about the possibility of public disorder, but concerns that issues of racism were being raised.

By referencing Creedon’s numbering system, we also find out that there were about thirteen undercover police officers targeting campaigning around Stephen Lawrence. Four or five were specifically targeting the Lawrence campaign, the remaining seven were on the periphery, either in left-wing groups or other protest movements with a focus on Lawrence.

So were they really interested in issues of public order, and widespread disruption? Well, according to an officer identified by the number N183, there were three main areas his team addressed.

Firstly, and remember this is before the Macpherson inquiry had concluded, they were tasked with finding out the terms in which institutional racism was being discussed within the community. Now the Machpherson inquiry sat through 1998 and it was only in 1999 that the final report was published. So during that time, the police were concerned not with the potential for public disorder but what would be the consequences for the police if they were found to be institutionally racist.

Firstly, and remember this is before the Macpherson inquiry had concluded, they were tasked with finding out the terms in which institutional racism was being discussed within the community. Now the Machpherson inquiry sat through 1998 and it was only in 1999 that the final report was published. So during that time, the police were concerned not with the potential for public disorder but what would be the consequences for the police if they were found to be institutionally racist.

Second, the police were concerned with how to manage the second stage of the inquiry. Now, the Macpherson inquiry did not just take place in government offices at Elephant and Castle. Macpherson decided to take the inquiry around the country, to listen to the views of different communities, because one of the terms of reference for the inquiry was ‘lessons to be learned’. So the inquiry went to Brixton, to Southall, to Bradford, to hear about local people’s experiences of policing. How to handle this stage of the inquiry was a big concern. N183 explained that Commissioner Condon’s plan was to stage a series of public forums that he would personally attend and set out the Metropolitan police’s position. One proposed venue was Lambeth town hall. Officer N81 was the closest spy in the Stephen Lawrence campaign and was able to advise N183, which local black groups should be excluded from that meeting.

The very fact that the second stage of the inquiry was to be held in black areas, where community concerns centred around police racism and police corruption, signalled the third area of concern: how to regain the trust and confidence of the black community. Even prior to the inquiry, a unit had been set up within the Metropolitan police: the C024 Racial and Violent Crime Task Force, headed by John Grieve, the former head of the Anti-terrorism team. At the time, we thought John Greive had been tasked with gathering intelligence on right-wing extremists and respond to criticism of racism within the Met, but what is now clear is that he was also gathering intelligence on the Stephen Lawrence campaign and those close to it. He admits for example that he authorised the secret taping of a meeting between Duwayne Brooks (Stephen’s friend and the main witness to Stephen’s murder) and his lawyers. Ellison concludes that this was unnecessary but lawful. Grieve justified his act, which involved the flouting of privilege rules, on the grounds that Dwayne had apparently given different versions of his statement. He needed an ‘unassailable record of what transpired’ in order to ‘protect the integrity of witness evidence’he claimed

Both the bugging and the Unit’s closeness to undercover officers raises critical issues of trust and accountability for us. Grieve now admits that at the time he was also tasked with providing a lead on the Metropolitan police’s response to the charge of institutional racism. What all this brings into question is the whole purpose of the C024 Racial and Violent Crime Task Force. As we now know that a number of police operatives spying on the black community had direct links with C024 such as N183.

During the Lawrence campaign we had many meetings where we planned for peaceful events. Both Ellison and Herne infer that police informers took back information from these meetings, not about threats of widespread disruption, but also about plans to call for the resignation of the police commissioner and his deputy. To me this is one of the real reasons why they saw the campaign as a real threat, its ability to influence public opinion on policing

‘Domestic extremism’ – never defined

Now if we go back and look at the remit of the SDS, its predecessors and forerunners, as well as its new avatars in the National Domestic Extremism and Public Order Unit, then it is clear that what we urgently need to concentrate on how ‘extremism’ is defined. There is no consensus even within the police about how ‘extremism’ should be defined. In fact, there is a difference between what the Home Office says about ‘extremism’ and what ACPO [Association of Chief Police Officers] says. Most worryingly, the lack of any exactitude means that peaceful protest can be defined as ‘extremism’ as can campaigners who have absolutely no criminal intent. The potential for widespread spying in this context, is vast.

It is very important to understand that even though we now have the promise of a judge-led inquiry into undercover policing, if these vague definitions of ‘extremism’ remain, we face a situation where spying is not only unregulated but becomes a permanent feature of society; similar to the situation in Northern Ireland where the weak framework provided by the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (which is meant to regulate covert policing) is a burning issue. A Northern Ireland civil rights group have told us that even though their most effective vehicle for police accountability is the Office of the Police Ombudsman (established after the Patten Commission),[iv] the Ombudsman is unable to control the role undercover police officers have in terms of a) setting the parameters of undercover policing and b) allowing undercover officers to commit criminal offences in an unaccountable and unacceptable manner.

I now know that a number of other campaigns that I coordinated, such as the Michael Menson, the Ricky Reel and the Blair Peach campaigns, were spied upon. These campaigns that I have been involved in had absolutely no intentions other than peaceful ones. But from Blair Peach to Stephen Lawrence, from Michael Menson to Nicky Jacobs, from the New Cross Massacre to the Campaign Against the Police Bill, from the Cherry Groce campaign to Broadwater Farm, every single one of these campaigns has been subject to surveillance. What we urgently need to do, starting from now, is to develop a strategy and build a campaign, which asks serious questions about who was spied upon, why they were spied upon, what was the nature of that spying and whether spying can be regulated properly and/or stopped.’

I now know that a number of other campaigns that I coordinated, such as the Michael Menson, the Ricky Reel and the Blair Peach campaigns, were spied upon. These campaigns that I have been involved in had absolutely no intentions other than peaceful ones. But from Blair Peach to Stephen Lawrence, from Michael Menson to Nicky Jacobs, from the New Cross Massacre to the Campaign Against the Police Bill, from the Cherry Groce campaign to Broadwater Farm, every single one of these campaigns has been subject to surveillance. What we urgently need to do, starting from now, is to develop a strategy and build a campaign, which asks serious questions about who was spied upon, why they were spied upon, what was the nature of that spying and whether spying can be regulated properly and/or stopped.’

Dear Recipient,

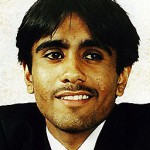

My mother was killed by a Police officer in March of 1989 (Wolverhampton, West Midlands). I would be immensely appreciative if you could spend a little time to visit the Justice Campaign website.

As an overview I have tried my utmost to challenge the findings of the Inquest and the Post Mortem (PM) Report therein. As expressed the PM Report was used as a strategic tool to send subliminal messages to the 10 Jurors as the PM report was fabricated as it blatantly claimed that Kishni Mahay (the deceased) had incurred Cirrhosis of the Liver as a result of incessant alcohol abuse across the years? The Coroner overseeing the Inquest Hearing also did not summon 2 key witnesses to appear as they clearly had said that my mother was on the Pedestrian Crossings at the point of the impact. The West Midlands Police have always claimed that my mother was in the “vicinity of the crossings.” Alas this is also a fantasy as I personally witnessed Police Officers attending the crime scene defacing the scene, one of mother’s shoes was kicked towards me as every possible attempt was made to move crash/incriminating debris away from the Crossings before RTA forensics arrived on the scene some 40 mins later.

I was assaulted and racially abused for no apparent reason at the scene as my mother lay lifeless and mangled on pavement 3 metres away. I was called Black Bastard, Paki Bastard on many occasions during that unforgettable evening. On the following day I went to the Police Station/Mortuary in Wednesfield, Wolverhampton and again I was met with threatening behaviours with racial undertones and I was told to back-off otherwise I may not see my 2 ½ year-old daughter grow up: whatever that was meant to imply?

None of the witness statements or investigation report content was ever shared with our Solicitor which made it difficult to get a secure handle on proceedings to effectively challenge any factors. Needless to say the Serious Crime Squad that operated had just been dispended as a result of high-profile corruption cases (e.g. Birmingham Six, Bridgewater Four etc…) I believe the timing of my mother death was still in a Police Culture that demonstrated such clear tendencies. In addition one of the officers in my mother’s death was then utilised to investigate the infamous Hillsborough Investigation looking at the South Yorkshire Police’s conduct during the Liverpool v Nottingham Forest Semi-Final game: sadly the results speak for themselves.

On conclusion this was a corrupt and callous Police Cover-up and evidence was deliberately suppressed for a Police Officer to evade certain prosecution by the Crown Prosecution Service. I had delivered a 3 hour presentation to the West Midlands Police at their HQ in Birmingham and I have not hesitated by claiming this was corrupt and racist Police Force and the only crime my mother had committed was that she was Asian and in their eyes expendable?

In 2015 I delivered a comprehensive dossier to 10 Downing Street for the attention of Prime Minister, Home Secretary and Justice Minister alas no reply.

Can you please help I have fighting this injustice for 3 decades. I will soon be launching an E-Petition to get the 100,000 on-line signatures to hopefully get a debate in the House of Commons Chamber which will lend itself to a an Independent Inquiry so my mother may get dignity in death, finally rest in peace and as a family we can move on as this elusive Closure will be achieved.

Happy to meet at your earliest convenience if you think that would be beneficial.

Please do not hesitate to contact of your require any assistance or clarity on any of the above. I look forward to your favourable in due course

Kind regards,

Raj Mahay

(Son of the Deceased, Key Witness and Justice Campaign Organiser)