Below we reproduce a speech at the eleventh annual Huntley Conference on the IRR’s Black History Collection and the importance of archives in signposting the past and future.

Today I want to talk to you about an item from the Black History Collection, which is held at the Institute of Race Relations. But before I get to that, I think I should tell you first how this collection came into existence. Now the Institute of Race Relations has been through two incarnations. It first existed in the 1950s as a colonial institution, its governing board was made up of colonial businessmen and ex-colonial administrators, as well as academics. It came out of a time when empire was vanishing, and its output was concerned with Britain’s imperial chickens coming home to roost, in other words with managing what it saw as the problem of ‘race’.

Now, in 1972, the Institute of Race Relations underwent a radical transformation. Its staff argued that the knowledge produced by the IRR served the interests of the ruling elite. After taking control of the IRR from the board of directors, staff began to serve the needs of black communities in Britain. A. Sivanandan, the IRR’s librarian, began to radicalise the Institute’s focus, turning the library into a resource for black communities engaged in activism in the UK, stocking materials on Black Power in the United States and on anti-colonial struggles around the world. In other words, the IRR began to address the realities of racism. The library’s staff saw the value in black journals, in things like flyers for political meetings, and in small pamphlets on a range of issues, from police brutality, the oppression of women, on the need for self defence and on self help projects.

By the 1990s, the IRR had a huge library of books, journals, pamphlets and so on, all from the movements that its gatherers were involved with at the time. Yet because of the radical break it had made, there was no longer the money to keep it going. The bulk of the collection was sent to Warwick University, where it might be made more accessible, yet material on pre- and post-war black settlements and Black political movements was kept. And with the help of a grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund, this became the Black History Collection of the Institute of Race Relations. The material we kept hold of reflected the way in which the IRR had, over time, analysed and educated about Black struggle.

We had already begun to record Black British History, because such history had been continually left out of accounts of British history, even out of working class history. When black history was taught, it centred around huge icons, such as Gandhi and Martin Luther King. The IRR felt it important that Black history should not exist as a thing apart, cut off from other histories, celebrated only in one month of the year and celebrating the lives of a few key individuals. We began to tell a counter narrative centred on a black history that was working class, all those who had colonial experience and experience of racism, and created by community-based movements in pursuit of equality and justice. And in doing so we begin to see how such movements not only transform communities in the UK, but also institutions such as trade unions, and concepts such as community safety and police accountability.

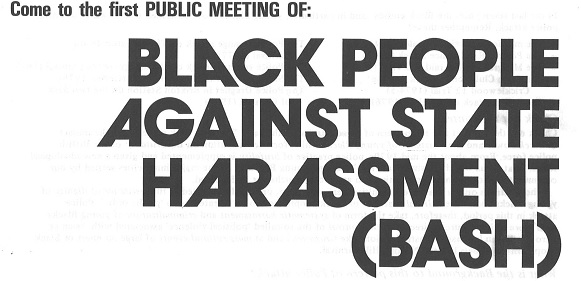

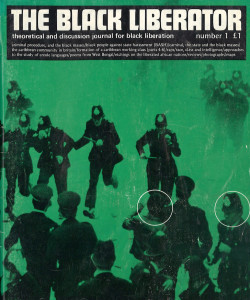

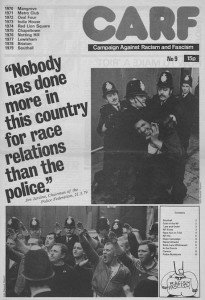

And this leads me to the document I’ve come to discuss today, an article about the formation of the Black People Against State Harassment Campaign, written by Colin Prescod (who just so happens to be here with us today), published in a radical black journal, The Black Liberator. The article I’ve chosen in here, about the formation of a campaign to fight police violence against black and Asian communities, shows the nature of the resistance to racism of the time. And it sums up the problems of police racism and shows that those problems still have not gone away.

Now, you can approach this article in any number of ways. First we could look at it in the context of an argument raging in black political movements at the time. Let me read you a few lines from the opening paragraphs:

‘In late 1970s Britain, the definition of anti-racism which tends to dominate white popular consciousness is one which confuses anti-racism with anti-fascism. If the white masses are led to believe that it is only if and when fascists like the National Front have public platforms, or come to power, that black people will really experience heavy racism – if this is to be believed, then with regard to the gross physical, economic, political, cultural and psychological attacks that are already being made against us, what’s that? We’ve got something to tell Europeans – their fascism is still alive and kicking in their civilization. The Black masses have been seeing the ‘fascist’ face of Britain since at least the 1950. Perhaps those Europeans who fear and abhor fascism, and who look back to their 1930s for their fascism, were they to look closely at the black experience in Britain, would find that they have been looking the wrong way for the resurgence of fascism.’

This passage chimes with a critique made by black political groups in the UK since at least the 1960s. And from this we can use the archives to look at the contribution of Black Power to the activism of black communities in the 1960s and ‘70s. With the influence and growth of Black Power within the UK, black political groups had been directing their activism not against the attitudes of individual racists (though this was also necessary), but against the actions of powerful British institutions such as the police force, and against the British state itself. But what it also tells us is that the black experience, and black peoples’ articulation of that experience, was crucial to informing, challenging, and redefining, white analysis and activism not just around racism but around the role of state power more generally.[1]

Another direction we could go into is to look at the activities of the Black People Against State Harassment Campaign. We can dig out of the archives the pamphlets and leaflets that the campaign put out. And we can see that the campaign was made up of a coalition of various groups all campaigning around the police practices that were affecting their communities. We can see that the campaign wasn’t just centred around London, but that it held demonstrations in Bradford too, in opposition to the immigration laws of the time. We can see that the campaign targeted Brixton police station, and can consider the way in which, for the black community, the police station was not just a symbol of police power; it was too often a graveyard. Already by the time BASH had launched, Aseta Simms and Michael Ferreira had lost their lives either in suspicious circumstances or as a result of failures of the duty of care in Stoke Newington Police Station. The deaths inside Brixton police station continue to this day. Outside the station, a tree stands carrying memorials for Ricky Bishop and Sean Rigg, who lost their lives in that place in 2001 and 2008. How might the activities of the Black People Against State Harassment campaign make us think about those memorials?

Let’s go back to the document, back to that first meeting of the Black People Against State Harassment campaign in Brixton, and take a look at who was there: women led groups such as Martha Osamor of the Scrap Sus Campaign and Brixton’s Black Women’s group; Brixton-based groups such as the Brixton Ad-Hoc Committee Against Police Repression; Legal advice centres such as the Black People’s Information Centre (Rudy Narayan, who worked there, would be charged in 1995 with inciting violence following a speech at a demonstration around the death of Wayne Douglas in Brixton police custody). There were Asian led groups such as the Bradford Asian Youth Movement, and Black groups whose membership was made up of Asians engaged in the same struggles against racism, such as the Black Socialist Alliance.

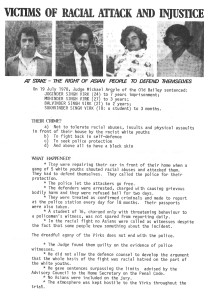

What this collective against police violence demonstrates is an organic community of resistance coming together against a shared oppression. Although its constituent members may have all experienced racism and police violence in different ways, at different points, and to different extents, all shared a common experience, and realised that there was strength in uniting their different campaigns under one banner, as one community. All realised the need to defend their communities both from racist attacks on the streets and from the police. Take for instance the case of the Virk Brothers. Four Asian brothers, in 1977 they were fixing there car when they were attacked by racists. They called the police and meanwhile defended themselves only to find that, when the police arrived, their attackers were freed and they were arrested themselves. As Colin writes in 1979 in the pages of The Black Liberator, ‘The Asian communities have come face to face with a dilemma long-known by Afro-Caribbeans. When black people defend themselves against physical attack, they are liable to be prosecuted for criminal acts.’

So there are countless ways in which we can look at a single piece of material from the archives, and as soon as you connect one historical document to another you’ll find that it can take you down any number of different but interconnected histories. But I want to talk now about how we can use history to connect to the present, to the struggles that young communities of colour are engaged in now. In many ways, the activism of black communities has effected real change, but in other ways things are the same as they ever were. How we understand that change has real implications for how we use history to educate and continue the fight against those entrenched forms of racism that continue, and the new forms of racism that are constantly developing.

Now the Institute of Race Relations publishes a journal which some of you may know of. Race & Class is a journal on issues of racism, empire and globalisation. Our latest issue focuses on the point that I just raised. Using the concept of ‘Reparative Histories’, the issue focuses on the implications of the past for the present, in particular the way in which the writing of history from above can write-out the agency of black political action. It asks what the implications are of this erasing of history from below. Now I want to read a few lines from it here:

Now the Institute of Race Relations publishes a journal which some of you may know of. Race & Class is a journal on issues of racism, empire and globalisation. Our latest issue focuses on the point that I just raised. Using the concept of ‘Reparative Histories’, the issue focuses on the implications of the past for the present, in particular the way in which the writing of history from above can write-out the agency of black political action. It asks what the implications are of this erasing of history from below. Now I want to read a few lines from it here:

‘How can we unpack those complex interconnections between past and present in the context of contemporary resistances to racism and the legacies of colonialism? In relation to slavery, if the call for reparations forces the contemporary world to face its slaving past, what does this do to the historical narratives which have structured those pasts? How do we reframe those narratives, to make them speak? How do we disrupt liberal narratives which seek to domesticate and cauterise the radical histories of resistance to white supremacy?’

So in other words, liberal narratives of the ‘march of progress’ give us a fairytale in which a kindly British state created an egalitarian society on behalf of its inhabitants. These histories either appropriate or cut out the actions of the state’s fiercest critics. If we put those actions in the forefront of our understanding of history, we don’t just undermine the legitimacy of those histories, we don’t just force the state to acknowledge its bloody history. We also put forward alternative, hidden histories of the work and the activism, that went into making change. And here we can use our archives to learn how to get things done.

I want to now go back to this document in The Black Liberator, back to that first meeting of the Black People Against State Harassment Campaign in 1978. Remember Martha Osamor, who attended on behalf of the Scrap Sus Campaign? Well it just so happens that in the next issue of the journal that I work for, we carry an interview with her about her life’s work in community organising to resist racial injustice. Reading about her life is not just an education in the post-war black experience in Britain; it is an education in what can be done to fight racism.

Martha came to Britain from Nigeria in 1963. The difficulties in finding housing and employment shattered all the talk of Britain as the Mother Country she had grown up with. But, as she tells us, in her words, the realisation that “you are not wanted” “also forms how you react and what you do about it.” After settling in a housing estate in Haringey, north London, and realising that the conditions that black people were living in were overcrowded, ‘second best’ as she puts it, the black residents decided to call a meeting. And this led to the creation of the United Black Women’s Action Group. They began to campaign not just around housing, but around a whole array of problems facing the community – policing, women’s rights, the quality of schooling and the exclusion of their children from schools. She describes how the community “started learning how to lobby and how things worked. Gradually, we became an organisation producing things and talking to people.”

And the organisation began to grow. The United Black Women’s Action Group became a vehicle for campaigning not just for those who lived on the estate, but also for others who were affected by the same issues. People whose children were getting into trouble with the police were getting in touch, and the organisation began to start work on the Scrap Sus Campaign (leading them eventually to the Black People Against State Harassment Campaign, where we began). And it began to dawn on them that it wasn’t just people in Haringey who were effected by the Sus laws; it was happening in Brixton, Deptford, all over the place. A network of people acting against Sus was needed, and so the United Black Women’s Action Group became a part of the Organisation of Women of Asian and African Descent, so that they might galvanise more people. In the early 1980s, Tottenham’s Broadwater Farm was facing heavy policing and the Broadwater Farm Youth Association was set up. After Cynthia Jarrett was killed during a police raid on her home in 1985, the Youth Association began making connections with those around the world facing similar state violence – those in Northern Ireland, South Africa and Palestine – and so the organisation grew into an international solidarity campaign.

Through reading about the actions of an unsung activist in Britain, we can see how communities under siege began to create their own institutions of justice in parallel to those established institutions that had failed them. And we can begin to ask questions over how to regroup, and rebuild. The killing of Mark Duggan in 2011 in Tottenham shows that the problem continues and has gotten worse. But a host of new campaigning groups – the United Friends and Families Campaign, the London Campaign Against Police Violence, and Defend the Right to Protest – are building their own communities of resistance.

So to sum up, an archive is not just about the past. It contains signposts for the future too. It teaches us to value what might not at first look valuable – pamphlets, leaflets and flyers are important to build up a picture of history. They are not just about detached objects but are indicators of live and interacting movements. And they contain the unofficial narratives, the history from below.

Related links

Search the catalogue of the IRR Back History Collection

IRR article: Martha Osamor: unsung hero of Britain’s black struggle

IRR article: The Race Relations Act 1965 – blessing or curse?