IRR Chair, Colin Prescod, reviews a collection of poetry, Beginning With Your Last Breath, by Roy McFarlane.

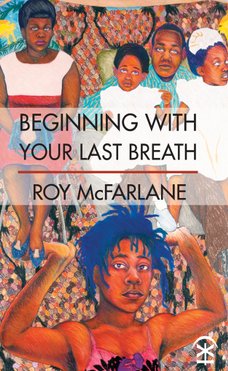

Roy McFarlane’s reputation goes before him – Birmingham Poet Laureate, Starbucks Poet in Residence, poet in residence at the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, just some of the accolades garnered. Beginning With Your Last Breath (Nine Arches Press, 2016) is his first full collection of poems to be published.

Roy McFarlane’s reputation goes before him – Birmingham Poet Laureate, Starbucks Poet in Residence, poet in residence at the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, just some of the accolades garnered. Beginning With Your Last Breath (Nine Arches Press, 2016) is his first full collection of poems to be published.

McFarlane’s writing is mostly disarmingly direct, almost without artifice, mixing rich descriptive prose and prosaic poetic imagery; poetry of fragments and poetic gestures; plain chant,

The woman in the photograph

surrounded by siblings looking just like me,

this was the woman who gave me away. (From ‘The weight of knowing’),

and dense memoir narratives containing poetic fragments;

I’m crying right now watching my mum holding on, each cough, each grunt, watching her getting ready to fly her maiden flight from my world into her paradise. They say big men don’t cry but I’m crying streams and rivers that are flowing into oceans. (From ‘I cried’);

sketches from memory and impressionistic reminiscences; catching and fixing telling moments from the West Indian living room and elevating the everyday,

Paterson was the old man of the neighbourhood

that young men drowning in oceans of puberty

navigating skies of spirituality

and living in times of uncertainty

found in him a lighthouse for all seasons. (From ‘Patterson’s House’.)

All these contradictions resolved by the poet’s intention,

I was writing city lyrics

the poetics of the oppressed, (From ‘Saturday Soup’)

Perhaps better to term such pieces in the collection ‘paroles’ as the French might, as distinct from poetry. Poetry is arguably a kind of strait-jacket: too strait a jacket for this smart free verse. McFarlane is free in his use of word-play and surprise-imagery, catching poetry in the common place, as in ‘Night and Day’,

I learned verses of love with

a beautiful two-toned Rudie,

her tights and t-shirts held

her as intimately as I did in the day time

in between lessons, common room

and the sports hall.

This is how the oral-archive of oral-cultures gets written up for us to read, and mouth, and savour. McFarlane is laying claim to a terrain of ‘telling’; collaging new settler-rhyme, and rhythm, and reckoning of life, loves and langours; of musics, jazz, reggae, and soul; of African, and Asian, and European conviviality; and of something ‘new’ being born, something Black, Brummie, and British:

‘Lost in Birmingham’

… do not arouse or awaken love until it so desires. Song of Solomon 3:5

She lives in the Electric theatre where once we watched Chico and Rita,

in sofas deep enough to hold to dreams and desires.

She’s in the Edwardian Tea Rooms sharing Earl Grey

and Cornish clotted cream scones on a summer afternoon.

She’s walking around the Rotunda along New Street listening

to the moan of love from a saxophone in the hands of a street busker.

She’s Andromeda waiting for Perseus

to release her from the halls of the Museum and Art Gallery.

She’s swallowed up in the silver whale of Selfridges;

entangled in the enchantment, consumed by her desires.

She’s speaking in tongues or saying confessions,

a wandering soul searching to be whole.

She’s homeless but believes, holding on to sweet memories.

Love that should never have ben stirred until the time was ready.

Hello old man, how ya doing, well i hope. Fond memories of NL angst and all. take care

Annie x