An update on BAME, refugee and migrant deaths in custody since September 2014.

To answer demands from supporters of the Black Lives Matter movement in the UK for up-to-date statistics on deaths in custody in the UK, the IRR has been trying to collect information on deaths which have taken place since its last reckoning (of 509 between 1991-September 2014) published in Dying for Justice. The IRR believes that at least forty suspicious deaths of people from a BAME, refugee or migrant background have taken place in the custody of UK authorities over the past six years: sixteen involving the police, nine in prisons and fifteen in immigration detention.

The IRR’s list from the IRR News’ coverage and that of Inquest’s extensive media releases attempts to ascertain those cases of deaths on the streets, in police vans, cells and other forms of detention where it is reasonable to suspect that either excessive use of force and restraint and/or negligence relating to healthcare and adequate assessments have contributed to a person’s death. See the lists here.

Restraint concern

We may not, unlike the US, have to deal on a regular basis with ever-trigger-happy cops. In this period, two deaths by police shooting (those of Jermaine Baker in 2015 and Trevor Smith in 2019) have been reported, but there are at least eight cases where police forces have used batons, tasers, cuffs, sprays, dogs and other forms of restraint on young black men acting erratically, but not criminally, who have gone on to die in their ‘care’.

What is significant in these deaths is the frequency in which mental illness and drug possession or addiction are part of the scenario, which ends in death by self-harm, stress caused by restraint and/or a lack of care. And this, despite the specific recommendation in the 2017 Angiolini report on deaths in police custody, that, ‘[n]ational policing policy, practice and training must reflect the now widely evident position that the use of force and restraint against anyone in mental health crisis or suffering from some form of drug or substance induced psychosis poses a life-threatening risk.’ [1]

Significantly, the Angiolini report found between 1990 and 2009, 16 per cent of those who died after the use of force were black, twice the proportion arrested. The review said: ‘Racial stereotyping may or may not be a significant contributory factor in some deaths in custody. However, unless investigatory bodies operate transparently and are seen to give all due consideration to the possibility that stereotyping may have occurred or that discrimination took place in any given case, families and communities will continue to feel that the system is stacked against them.’

The stereotypes that black men will be ‘mad or bad’ and if not prone to violence will be faking illness are still, judging from evidence at inquests, apparently behind police reactions. And, of course, recent cuts in services for the mentally ill (closing of institutions) and removal of support services (for addiction problems) has impacted on families. Austerity has helped to structure violence.

In the case of deaths of foreign national prisoners and those in immigration detention, the racism is effectively built into the system. People die, often at their own hand, because they are afraid of deportation, because they are facing indefinite incarceration, because they cannot access care for their physical and mental health commensurate with that of the ‘free world’.

Impunity

What does link the UK with the US experience however, is the issue of impunity. Despite all the paper recommendations, all the instructions as to how to examine someone suspected of ingesting drugs, how and when to use ‘proportionate’ force, not one officer has been convicted since the IRR started collecting figures on black deaths in 1969 – when David Oluwale was hounded by police into the River Aire. Despite all the critical narrative conclusions added by conscientious jurors at inquests, the same sort of conduct is being excused and/or condoned over and over again.

And despite damning inquest verdicts, prosecutions are either not brought, or officers are ultimately found in the criminal court system to be not guilty. [2] For example, the killing of Christopher Alder in 1998 was deemed at inquest an ‘unlawful killing’, there was a prosecution of five officers who were later acquitted on the word of the judge; ‘unsuitable force’ was deemed by the inquest to have taken place to cause the 2008 death of Sean Rigg – after the coroner ruled out ‘unlawful killing’ as a possible verdict – an officer was prosecuted and found not guilty; in the 2011 killing of Kingsley Burrell, the Independent Police Complaints Commission arrested four officers on suspicion of manslaughter by gross negligence and misconduct in public office, but the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) declined to prosecute on the basis of lack of evidence. There has been just one successful prosecution of the police following a BAME death in custody to our knowledge – in the case of the shooting dead of Jean Charles de Menezes (mistaken as a terrorist in 2005) and that only under Health and Safety legislation.

And to add insult to fatal injury, for the bereaved families waiting to find out how a loved one died, when they can lay a body to rest, who might be responsible, and how to prevent such a fate for others, the system grinds at an unbelievably slow pace, as institutions pass or fail to pass information, sit on reports, lose files and so on. Sheku Bayoh died five years ago in Scotland, the family still awaits the promised public inquiry. Jermaine Baker, too, died five years ago but at the hand of a police marksman, with no inquest held and the promised inquiry still awaited. In the case of Darren Cumberbatch, who died in July 2017, the promised review of the death by the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC) has not been held because the transcript from the inquest, held over a year ago, has not reached the IOPC yet.

Further information

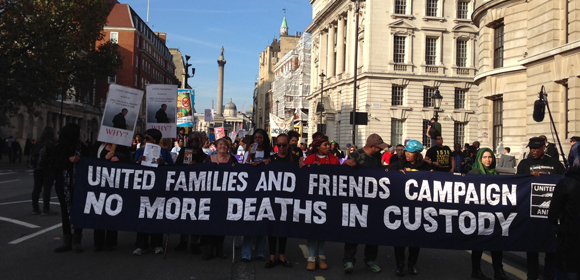

We are merely providing here a snapshot of what is taking place in the UK. For further information on the progress of particular cases, consult the details on the site of Inquest; and to support the work of families of the bereaved, contact United Families and Friends (UFFC).

The individuals which we might include in any tally of deaths are not there purely because of their ethnic background or immigration status. Nor are we suggesting in any way that deaths of non-BAME people do not take place, or have a lesser value. What we are trying to investigate is whether and how racism, through the action or inaction of individuals and the systems of criminal justice and immigration control, have contributed to a death. In other words, whether a non-BAME person in similar circumstances would have been treated in a different way. And we have taken into account concerns expressed by witnesses, family members, organisations such as UFFC and Inquest and also evidence that emerges during an inquest (although we might not be bound to agree with a coroner’s instruction or an inquest verdict).

Ours is not an official or an exhaustive list and we welcome corrections and additions. Please leave a comment on our site or contact us by email at info@irr.org.uk

Thank you for your support.

I am the mother of Cameron Whelan your list has the date of his death wrong.

Cameron drown on 25th May 2018.

Thank you Ms. Whelan for bringing this to our attention and apologies for the error. We have changed the text so that it’s accurate. Take care, IRR News Team

Cameron Whelan drown on 25th May 2018.

Thank you for your support.