Daniel Holder from the Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) reflects on the recently introduced Counter Extremism Strategy and the scenario which we would see if the strategy was applied in Northern Ireland.

Margaret Thatcher famously claimed Northern Ireland was as British as her own constituency, Finchley. Apparently however we are officially no longer as ‘extremist’ as Finchley. Number 10’s recently launched new Counter Extremism Strategy will not apply here. The document follows the earlier ‘Prevent’ strategy’s definition of ‘extremism’ as ‘vocal or active opposition to fundamental British values’ and among other measures plans:

Margaret Thatcher famously claimed Northern Ireland was as British as her own constituency, Finchley. Apparently however we are officially no longer as ‘extremist’ as Finchley. Number 10’s recently launched new Counter Extremism Strategy will not apply here. The document follows the earlier ‘Prevent’ strategy’s definition of ‘extremism’ as ‘vocal or active opposition to fundamental British values’ and among other measures plans:

- Extremist disruption orders (a type of ASBO for ‘extremists’);

- Powers to ban non-violent ‘extremist’ organisations;

- Powers to ban ‘extremists’ from the airwaves;

- Encouraging the public to report ‘extremists’ in their mist and duties that the police must fully’ follow up such reports;

We have seen the like of this before. Our experience dictates that the Strategy is only likely to become a vehicle for the institutionalisation of prejudice against target groups that will further the ‘segregation and alienation’ that the prime ministerial foreword paradoxically claims is ‘fertile ground for extremist messages to take root’. Injustice at home and abroad breeds anger, this Strategy like others before it will compound not redress injustice.

One initial question is whether the Strategy is really designed to do what it says it is going to do, and how that relates to the particular circumstances of Northern Ireland. The prime ministerial foreword to the Strategy singles out the need to tackle racist ideologies, neo-Nazis ‘and, of course, Islamist extremism.’ The Strategy goes on to repeat claims it aims to tackle the far right and ‘those who promote hatred.’ Whatever the hyperbole of Belfast being dubbed the ‘race hate capital of Europe’ over a decade ago we continue to be plagued by orchestrated racist (including sectarian) incidents with paramilitary involvement. Yet Whitehall nevertheless seems strangely relaxed about not applying its flagship strategy here.

There are other strange things in relation to the context of the policy. Firstly, it does not escape notice that there are already significant obligations (that could be deployed on both sides of the Irish Sea) to further tackle incitement to hatred. These obligations form part of human rights treaties the UK has long signed up to, but refuses to implement.  Take the UN anti-racism convention (ICERD) which commits the UK to outlaw ’all dissemination of ideas based on racial superiority or hatred, incitement to racial discrimination, as well as all acts of violence or incitement to such acts against any race or group of persons of another colour or ethnic origin…’ In relation to banning organisations ICERD commits the UK to: ‘declare illegal and prohibit organizations, and also organized and all other propaganda activities, which promote and incite racial discrimination’. The current Counter Extremism Strategy is smattered with sample quotes of ‘extremist’ speech, including that attributed to ‘Islamic Extremists’, all of which could be challenged as advocacy of ethnic or religious hatred. Whilst there is already legislation in Britain (and stronger legislation in Northern Ireland) that criminalises incitement to hatred on ethnic and religious grounds, such laws set a high threshold and fall well short of what is required under treaties like ICERD. Yet despite being repeatedly urged to do so by UN committees the UK has steadfastly refused to fully legislate to implement these international obligations on the grounds that they might interfere with the British value of free speech. This objection is ill founded. Recent years have seen considerable work to codify the threshold test between protected freedom of expression on the one hand and incitement to hatred on the other. The UN Rabat Plan of Action sets out a six stage test focusing on harm and context. It is also notable that in relation to other conduct that is already outlawed the Counter Extremism Strategy document concedes that speech or conduct that advocates violence is already a criminal offence. Furthermore the government has also already legislated for broadly drafted powers to outlaw the ‘encouragement of terrorism’, and included the likes of the ISIL, referenced throughout the Counter Extremism Strategy, in its official list of terrorist organisations.

Take the UN anti-racism convention (ICERD) which commits the UK to outlaw ’all dissemination of ideas based on racial superiority or hatred, incitement to racial discrimination, as well as all acts of violence or incitement to such acts against any race or group of persons of another colour or ethnic origin…’ In relation to banning organisations ICERD commits the UK to: ‘declare illegal and prohibit organizations, and also organized and all other propaganda activities, which promote and incite racial discrimination’. The current Counter Extremism Strategy is smattered with sample quotes of ‘extremist’ speech, including that attributed to ‘Islamic Extremists’, all of which could be challenged as advocacy of ethnic or religious hatred. Whilst there is already legislation in Britain (and stronger legislation in Northern Ireland) that criminalises incitement to hatred on ethnic and religious grounds, such laws set a high threshold and fall well short of what is required under treaties like ICERD. Yet despite being repeatedly urged to do so by UN committees the UK has steadfastly refused to fully legislate to implement these international obligations on the grounds that they might interfere with the British value of free speech. This objection is ill founded. Recent years have seen considerable work to codify the threshold test between protected freedom of expression on the one hand and incitement to hatred on the other. The UN Rabat Plan of Action sets out a six stage test focusing on harm and context. It is also notable that in relation to other conduct that is already outlawed the Counter Extremism Strategy document concedes that speech or conduct that advocates violence is already a criminal offence. Furthermore the government has also already legislated for broadly drafted powers to outlaw the ‘encouragement of terrorism’, and included the likes of the ISIL, referenced throughout the Counter Extremism Strategy, in its official list of terrorist organisations.

All of this prompts some questions. Just what and who else is the broader concept of ‘extremism’ (as defined as opposition to British values) intended to catch? If the Strategy really is a vehicle to tackle ‘hatred’ why is government both resisting relevant treaty-based commitments on that very subject and sparing the ‘race hate capital of Europe’ the Strategy?

A footnote on the contents page reveals the official answer to the last question. Legally speaking, the British government’s problem is that ‘counter-extremism’ is an ideological concept it has just made up. This means it is not on the list of policy areas retained by the Westminster Parliament included in schedules to the 1998 implementation legislation of the Good Friday Agreement. The legislation would therefore have to pass through the Northern Ireland Assembly and London knows that the Irish nationalist parties, themselves representative of past suspect communities, would block it. This might not stop Whitehall implementing other parts of the Strategy here that do not need legislation, but it does not appear minded to. This is suspiciously respectful behaviour for what is a flagship policy. Contrast it to the fury that has led to economic sanctions totalling £114 million this year alone on the Belfast institutions for the refusal to implement the Welfare Reform Act 2012.

There are however other reasons why officials might be relieved that the Strategy does not apply here. Firstly it would have been complicated to police allegiance to British values of those who constitutionally do not have to be British. Secondly the Strategy could either have been just targeted at Muslims and be challenged as blatantly discriminatory or alternatively be equally applied to active opposition to British values from what the Strategy would consequently label ‘Christian Extremists’ as much as it would be to ‘Islamic Extremists’. The conundrum is such even-handedness would have risked significant conflict with sections of our local political establishment.

Counter-extremism, violence and Britishness in the Irish context

The Counter Extremism Strategy borrows some language and concepts that have been around for some time under the guise of projects for ‘community cohesion’ and British Bills of Rights. Both have tended to extol ‘British values’ and ‘British rights’ as both being profoundly important but incapable of definition. More recent discourse has singled out the right to jury trial, for example, as a British right (one which ironically does not apply in British-as-Finchley Northern Ireland). The new Strategy goes further and provides definitions of both ‘extremism’ and ‘British values’.

The Counter Extremism Strategy borrows some language and concepts that have been around for some time under the guise of projects for ‘community cohesion’ and British Bills of Rights. Both have tended to extol ‘British values’ and ‘British rights’ as both being profoundly important but incapable of definition. More recent discourse has singled out the right to jury trial, for example, as a British right (one which ironically does not apply in British-as-Finchley Northern Ireland). The new Strategy goes further and provides definitions of both ‘extremism’ and ‘British values’.

After the classification of opposition to British values, a second part of the definition of extremism designates advocating killings as being extremist – but only some killings. It  might seem reasonable to think that tearing up the UN Charter and launching, partaking in and supporting illegal wars of aggression in Iraq and Afghanistan that have left hundreds of thousands of people dead is pretty extreme. Yet Tony Blair is unlikely to be the recipient of the first extremist ASBO. The definition precludes both these examples from being considered ‘extreme.’ Only advocating killing of members of the UK’s armed forces is to be considered ‘extremism.’ In this sense ‘extremism’ becomes a further ideological tool (like the concept of ‘terrorism’ before it) to separate ‘good’ violence from ‘bad’ violence. Extremist violence is abhorrent but much more widespread violence by the UK and its allies is not abhorrent, rather it is bestowed some legitimacy. This is a problem for those of us who oppose all forms of illegitimate violence. The Strategy proposes to do nothing to redress alienation fuelled by knowledge of British foreign policy. Equally problematically this part of the definition, when read alongside the broader rhetoric in the Strategy, reads more and more like a test designed to root out the disloyal citizens. The Strategy plans changes to ensure rules are toughened up to ensure ‘the privilege’ of British citizenship can be stripped from those who ‘reject our [British] values’. The problem that would emerge if government took forward its stated desire to apply the Strategy to Northern Ireland is that the Belfast / Good Friday Agreement (GFA) conceded people here do not have to be loyal British citizens, or indeed British at all. Under the GFA both London and Dublin:

might seem reasonable to think that tearing up the UN Charter and launching, partaking in and supporting illegal wars of aggression in Iraq and Afghanistan that have left hundreds of thousands of people dead is pretty extreme. Yet Tony Blair is unlikely to be the recipient of the first extremist ASBO. The definition precludes both these examples from being considered ‘extreme.’ Only advocating killing of members of the UK’s armed forces is to be considered ‘extremism.’ In this sense ‘extremism’ becomes a further ideological tool (like the concept of ‘terrorism’ before it) to separate ‘good’ violence from ‘bad’ violence. Extremist violence is abhorrent but much more widespread violence by the UK and its allies is not abhorrent, rather it is bestowed some legitimacy. This is a problem for those of us who oppose all forms of illegitimate violence. The Strategy proposes to do nothing to redress alienation fuelled by knowledge of British foreign policy. Equally problematically this part of the definition, when read alongside the broader rhetoric in the Strategy, reads more and more like a test designed to root out the disloyal citizens. The Strategy plans changes to ensure rules are toughened up to ensure ‘the privilege’ of British citizenship can be stripped from those who ‘reject our [British] values’. The problem that would emerge if government took forward its stated desire to apply the Strategy to Northern Ireland is that the Belfast / Good Friday Agreement (GFA) conceded people here do not have to be loyal British citizens, or indeed British at all. Under the GFA both London and Dublin:

…recognise the birthright of all the people of Northern Ireland to identify themselves and be accepted as Irish or British, or both, as they may so choose, and accordingly confirm that their right to hold both British and Irish citizenship…

UK law continues to bestow British citizenship on persons born in Northern Ireland of Irish (or British) parentage. That Irish citizens here be stripped of British citizenship for failing to show sufficient Britishness would border on the farcical. Much the same difficulties apply to the Strategy’s underpinning stipulation that everyone must abide by ‘British values’ in a part of the jurisdiction where you do not have to be British. The constitutional framework of the GFA also provides that the power the British government deploys in the north: “… shall be exercised with rigorous impartiality on behalf of all the people in the diversity of their identities and traditions”. This particular provision is notably not restricted to those who identify as ‘British’ or ‘Irish’. Whilst such a framework does not extend over the Irish Sea it nevertheless appears no less absurd in the ‘globalised’ 21st century to require the population of, say the south east of England, to all be British, and to demonstrate their adherence to British values and allegiance to UK armed forces.

That said there is nothing objectionable about the ‘British values’ that have finally been defined in the document. The values include ‘the rule of law, democracy, individual liberty and the mutual respect, tolerance and understanding of different faiths and beliefs’. It elaborates on a British value of belief in equality, speaking of the ‘damage caused by discrimination on the basis of religion, race, gender, disability or sexual orientation’. The document concedes that there is nothing exclusively British about these values. Indeed all of the above are all fundamental internationally recognised elements of a human rights framework. The problem is that rather than being articulated as such, they are being attached to Britishness in a manner which locates the problem as being that the non-British other (Irish or otherwise) does not ‘share our values.’ This does not sound too dissimilar from popular racist discourse and is only likely to fuel prejudice and alienation.

Falling foul of British Values in Northern Ireland

The second problem for government would have been that unless there was unequal enforcement active opposition to ‘fundamental British values’ such as ‘mutual respect, tolerance and understanding of different faiths and beliefs’ and equality and non-discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, some powerful people and institutions, many of whom would proudly identify as British, could well have been labelled as extremist.

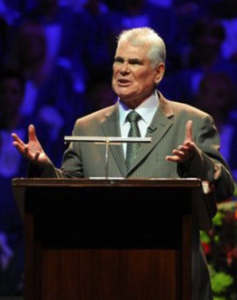

Among them could be Evangelical Pastor James McConnell for his widely publicised address at the Whitewell Metropolitan Tabernacle Church in which he stated ‘Islam is heathen, Islam is satanic, Islam is a doctrine spawned in  hell’ and warned of the ‘new evil’ of ‘cells of Muslims.’ An extremist ASBO is unlikely to go down well with Northern Ireland’s First Minister Peter Robinson of the DUP who leapt to Pastor McConnell’s defence complaining he had been demonised and for good measure added ‘I’ll be quite honest, I wouldn’t trust them [Muslims] in terms of those who have been involved in terrorist activities. I wouldn’t trust them if they are devoted to Sharia Law. I wouldn’t trust them for spiritual guidance’ but did say Muslims were trustworthy in matters like going to the shops for him.

hell’ and warned of the ‘new evil’ of ‘cells of Muslims.’ An extremist ASBO is unlikely to go down well with Northern Ireland’s First Minister Peter Robinson of the DUP who leapt to Pastor McConnell’s defence complaining he had been demonised and for good measure added ‘I’ll be quite honest, I wouldn’t trust them [Muslims] in terms of those who have been involved in terrorist activities. I wouldn’t trust them if they are devoted to Sharia Law. I wouldn’t trust them for spiritual guidance’ but did say Muslims were trustworthy in matters like going to the shops for him.

Senior DUP figures may also run into trouble over opposition to equality on grounds of sexual orientation. The party developed a private member’s bill to amend the Equality Act (Sexual Orientation) Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2006, to legalise certain forms of currently unlawful discrimination when done in pursuance of religious conscience. This bill, which would apply to service provision, follows the Ashers Bakery case where this large business received a small fine for cancelling an order from a gay man for a cake with a marriage equality slogan on it (and is currently appealing the decision). The run up to the original trial saw a huge rally organised by the Christian Institute where several thousand cheering supporters of the Bakery’s Christian owners including DUP ministers past and present, packed Belfast’s Waterfront concert hall, and hundreds more packed the pavements outside. According to the logic of the Counter Extremism Strategy all were guilty of the common purpose of vocal and active opposition to a fundamental British value.

Comments by senior DUP figures which also conflict with this British value may also find themselves under greater scrutiny should the letter of the Strategy be implemented. A DUP health minister Jim Wells MLA, told voters at a hustings event last April ‘You don’t bring a child up in a homosexual relationship. That a child is far more likely to be abused and neglected…’ Mr Robinson’s wife Iris, also then an Assembly member and chair of its health committee, in addition to describing homosexuality as ‘comparable’ to child abuse, also described being gay as an ‘abomination’ but one that gay people could be cured from and ‘turned’ heterosexual with suitable psychiatric help. Mrs Robinson also set out her position that the role of government was to ‘uphold God’s law morally’ and to ‘represent the morals of the scriptures.’ Yet the Counter Extremism Strategy makes clear that government will only tolerate only ‘one rule of law in our country’ and will ‘never countenance’ alternative systems of law ‘informed by religious principles.’

Religious and political institutions themselves are also going to have to be careful they fall foul of opposing the British value of ‘mutual respect, tolerance and understanding of different faiths and beliefs’. For example every member of the Orange Order, itself heavily part of the Unionist establishment here, is pledged to: “strenuously oppose the fatal errors and doctrines of the Church of Rome, and scrupulously avoid countenancing (by his presence or otherwise) any act of ceremony of Popish worship; he should by all lawful means, resist the ascendancy of that Church, its encroachments, and the extension of its powers”. Another rule reportedly stipulates that ‘Any member dishonouring the institution by marrying a Roman Catholic or attending any of the unscriptural, superstitious and idolatrous worship of the Church of Rome shall be expelled.’ Far from labelling the organisation as extremist the UK government designates the Orange Order’s main parading day (12 July) as a Bank Holiday. The re-routing of a relatively small number of the Order’s marches away from counter-protestors or nationalist areas has been the biggest public order issue here for many years – government would not relish the backlash if it designates the institution as ‘extremist’ under its new Strategy. Furthermore if the Order was captured by the ‘extremism’ definition of opposing the above British value, it would not of course not be the only Christian organisation, Protestant, Catholic or otherwise whose rules or teachings would do so. This raises the question of the boundary of what is protected as manifestation of freedom of expression (including religious expression) and what is not.

As alluded to above there has been a lot of work done on bringing legal certainty to the concept of advocacy of hatred, as distinct from protected freedom of expression. It is only those matters which genuinely reach the threshold of internationally recognised advocacy of hatred, hostility or discrimination on religious, ethnic, LGBT and other grounds that should be pursued as such. By contrast the selective application of the more subjective concept of ‘extremism’ is what appears to be in store under the new Strategy. Stripped back into context the concept and Strategy and the manner in which they are framed look more like the establishment reasserting British nationalism. The folly of doing that in a divided society in a context like that which exists in the north of Ireland is plain to see. Yet it is likely to be no less ‘divisive’ elsewhere.