I found myself in a tearful state on my first visit to ‘The Robinson Institute’ exhibition, curated by artist Patrick Keiller in the main hall at Tate Britain – moved to tears, but wearing a big grinning smile on my face.

I’ve been back several times now and I’ve had that ‘tears of joy’ moment every time. It is the surprise – surprise at coming upon a kindred spirit, surprise at coming across brilliant common sense and unvarnished plain truths elegantly conveyed in an arts’ exhibition. In the spirit of ‘the occupy movement’ – I urge you to see this exhibition.

The introductory wall text, at once prosaic and poetic, announces that: ‘The Robinson Institute aims to promote political and economic change by developing the transformative potential of images of landscape [what is contained within as well as what is evoked – CP]. It continues the work of an itinerant scholar known as Robinson, whose last known project is the basis for the Institute’s inaugural display. In early 2008 he set out, with an ancient cine camera, to walk through landscapes in southern England: the location’, he wrote, ‘of a Great Malady, that I shall dispel, in the manner of Turner by making picturesque views, on journeys to sites of scientific and historic interest.’

But that announcement does not quite prepare you for what you are about to receive. Keiller’s is a work of the imagination – and on this journey with his Robinson you will encounter, amongst other notables, historians, like Hobsbawm; philosophers, like Borges; political economists, like the Karls Marx and Polanyi; scientists, like Charles Lyell whose 1830 Principles of Geology demonstrated that the biblical timescale of creation was no longer credible. You will also come across Kathleen Ferrier singing Goethe in a Brahms rhapsody, and Shelley’s poem ‘The Masque of Anarchy’. And Keiller weaves in references to the historical date on which Imperialists tried to fix which nations would have the right to develop atomic and then nuclear weapons technology, and the incident of the Autumn 2008 collapse of the Lehman Brother’s Bank which signaled the arrival of a new and current moment of crisis for capital.

But that announcement does not quite prepare you for what you are about to receive. Keiller’s is a work of the imagination – and on this journey with his Robinson you will encounter, amongst other notables, historians, like Hobsbawm; philosophers, like Borges; political economists, like the Karls Marx and Polanyi; scientists, like Charles Lyell whose 1830 Principles of Geology demonstrated that the biblical timescale of creation was no longer credible. You will also come across Kathleen Ferrier singing Goethe in a Brahms rhapsody, and Shelley’s poem ‘The Masque of Anarchy’. And Keiller weaves in references to the historical date on which Imperialists tried to fix which nations would have the right to develop atomic and then nuclear weapons technology, and the incident of the Autumn 2008 collapse of the Lehman Brother’s Bank which signaled the arrival of a new and current moment of crisis for capital.

You will have to spend some time with Keiller’s work. You will have, literally, to work out where it starts as well as what it is showing and saying – or rather, what it is pointing at.

Keiller constructs, or is this really de-constructs, Robinson’s journey through the landscape of south east England to take in seven stops, seven secular stations of a secular cross – at (1) Robinsonism, he introduces us to the ‘itinerant scholar’ traveling temporally as well as conceptually; in 1795 Newbury (2), we are reminded that ‘one of the factors that enabled industrial capitalism to develop first in England was the mobility of the previously settled agricultural workforce. Such labour-market flexibility, however, derived not from any Anglo-Saxon, customary freedoms, but from government legislation: An Act to prevent the Removal of Poor Persons until they shall actually become chargeable, like the 1975 amendment to the Settlement Act in the interest of freeing hands to go where burgeoning capitalist enterprise needed them most.’ At (3) Greenham Common, Aldermaston, and the Government pipeline and storage system, we ruminate on the interconnectedness of industrialisation, fossil fuels and war-economy; at (4) we are encouraged to contemplate The non-human, the post-human, where ‘biophilia’ faces off against ecological collapse; at (5) Agriculture, we are invited to reflect amongst other things on the 21st century irony of a land rich in arable crops mostly now not for human consumption, and where Robinson has ‘rarely seen anyone working in the fields’; 1830 (6) is when the five year ‘Revolution of Otmoor’ against enclosure began, and at this same place but in our time a major oil pipeline now runs across the landscape; and at (7) we arrive and stop at ‘Hanged, drawn and quartered’ where, as with any other stop in the thoroughly developed English landscape, we are encouraged to investigate how ‘this could be a place of historical importance’ – take the vicinity of the Cherwell river at Enslow Hill, say, where three anti-enclosure rebels were indeed hanged drawn and quartered in 1536, and where as well on Christmas Eve in 1874, 34 were killed and 69 injured in a train crash at nearby Hampton Gay.

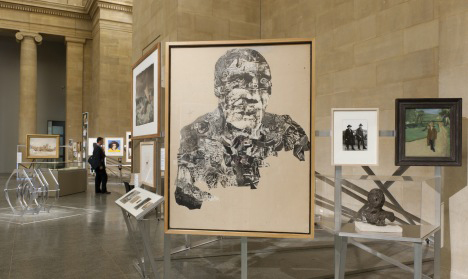

At every station of this informed and imaginative journey in the gallery space, there is a kind of incendiary juxtaposition of text and artworks extracted from the Tate’s rich and fine collection, with samples of Keiller’s own film and photography work mixed in – Jackson Pollock ‘Number 23’, Andreas Gursky “Bahrain 1’, Leonard Rossoman ‘Bomb falling into water’, a variety of JMW Turners, William Blake ’Wat Tyler and the Tax Gatherer’, Richard Long ‘The Crossing Place of Road and River’, Graham Sutherland ‘Entrance to a Lane’, L.S Lowry ‘Industrial Landscape’. I found myself particularly drawn to a little known work, Eileen Agar’s 1938 ‘The Reaper’, gouache and mixed media on an A4 sized sheet of paper – in which a dried out, found leaf makes the big wheel of an impressionistically sketched motorised farm vehicle. The artworks provide context for ideas, and the noted ideas do the same for the re-appreciation of the artworks. Then, stirred by Keiller’s barrage of provocations, we find a section of tables with the actual books that will have aided Robinson’s scholarly investigations of the landscape, and chairs where you might sit and look through glass or flick through the pages of a number of the book texts referenced in the exhibition. Have a pen or pencil and paper handy. You will want to make a note or two. If like me you’ve asked the question ‘what are museums for in our time?’ – here’s one answer. Keiller has curated an oasis space of contemplation in the incessant noise of our age of information overload.

I’ll go!