Despite the assurances given to a parliamentary committee, asylum housing providers are still neglecting the health and welfare of vulnerable residents including young children, says John Grayson of South Yorkshire Migration & Asylum Action Group, continuing his investigations.

In 2015, Anne and her husband Simon fled from their home in the war-torn Middle East with their four daughters Christine, Zoe, Maddy and newborn Becky. They travelled across Turkey to try to reach the safety of Europe. The family were crossing the Aegean when their boat sank. The Turkish authorities managed to airlift them out of the water. They have kept a copy of a Turkish newspaper reporting the rescue ever since

Becky, then a baby and now five, was born with learning and physical disabilities and was further injured in these traumatic events.

Anne told me through an Arabic interpreter, ‘We spent the next three years crossing Europe. We came through Greece and Switzerland. Sam was born in 2017. In Switzerland the doctors helped Becky and gave her a caliper for her leg. Last year we all came to France. Then I came to the UK in January with Becky and Sam and my two daughters Christine and Zoe. My husband Simon and oldest daughter Maddy had to stay in France. We really miss them and ring them every day.

‘When we came to the UK we went to the police and were told we were in Wakefield. They sent us to a hotel in Wakefield. We stayed there from 26 January to 12 March. We had two connecting rooms with our own bathrooms, but there was nothing at all for Becky and Sam. No place to play and no toys.’

Christine, who speaks a little English and also used my Arabic interpreter, told me, ‘A nurse came and checked our health. She talked of helping Becky. She went away and we never saw her again. Then we all had to go to London. We stayed in a really bad hostel in a tiny room up lots of stairs from 12 to 17 March. We were fingerprinted and interviewed. Then we had to come back to a Bradford hotel. There we had a big room with bathroom. We were sent here to Urban House on 20 March. I don’t know why.’

Thus, three days before the lockdown, the family were sent from a hotel, where they were able to self-isolate with their own bathroom and toilet and where social distancing was possible, to a crowded Urban House to face shared toilets and showers and a canteen and public areas with no social distancing.

Urban House residents adopt the family

The other residents in Urban House have adopted the family. Douglas, a professional worker from the Middle East, told me, ‘Everybody in Urban House thinks this family must be the first to be moved out. The little girl, I have heard, when she is sleeping struggles for breath and keeps waking. They only give her an old-type inhaler; she needs proper medical help. They are in a terrible state – they look as if they are in shock all the time. They need medical help for their trauma. They try to ring the father all the time.’

Douglas went on, ‘Becky has one leg in a support and has very little movement in her right hand. The management here all throughout their stay refused to give Anne a buggy for Becky. They said the one they gave was a loan and kept taking it back.’

SYMAAG took a specialist buggy from a charity in Sheffield to Urban House for Becky.

Anne tells me, ‘I have diabetes and I inject insulin. I have been many times to see the nurses for myself and Becky. They do not help me; I ask to see doctors and hospital for Becky. They tell me I will have to wait until I go to an asylum house.’

Douglas tells me, ‘They are all in a large family room in Urban House but have only a hand basin and have to share toilets and showers with everyone.’

Anne and her family have thus been in Urban House throughout the lockdown period from 20 March with medical conditions which Public Health England has stated puts them at risk of Covid-19.

Mears’ £1.15 bn contract with the Home Office is clear on what Mears and their subcontractor, Urban Housing Services LLP, should do when residents need medical services:

‘Where a Service User is taken ill during Service provision, the Provider shall ensure that access to medical treatment is made available (including, if required, the attendance of appropriate medical staff), and if necessary, shall take the Service User to hospital. The Provider shall notify the Authority (the Home Office) as soon as possible from taking the decision to provide access to medical treatment or to take a Service User to hospital.’

A junior doctor, Rory, who works at a Wakefield hospital and has been helping to get healthy food and toiletries into Urban House,[1] told me, ‘I have been making enquiries at the local hospital trusts why people in Urban House are not allowed to register with GPs. I am not getting any answers. People who have their proof of status and NASS support have to be given access to NHS primary care. It is their right.’

Disabled and ‘shielding’, abandoned to rats and cockroaches

I received a phone call; it was a woman’s voice. ‘I was told you might be able to help one of my clients in a Mears house in Sheffield.’ The call was from Pamela, ‘I am a care worker who has been looking after Katy, a severely disabled woman and Mandy her five-year-old, in a really tiny flat. Things here in Katy’s flat are awful. There are rats running around even in the daytime. The pest control man said they are coming up under the shower base in the bathroom. He has put poison boxes down. I saw a poisoned rat coming out into the bathroom and I put it down the toilet. Katy has seen a rat running over the beds. The flat is very damp and humid and there are cockroaches everywhere. There is a drip leak over Mandy’s bed from the flat above. Every day, when I come, her bed is wet, and I have to change all the bedclothes. We both ring Migrant Help all the time, but they never get the Mears repairmen here.

I received a phone call; it was a woman’s voice. ‘I was told you might be able to help one of my clients in a Mears house in Sheffield.’ The call was from Pamela, ‘I am a care worker who has been looking after Katy, a severely disabled woman and Mandy her five-year-old, in a really tiny flat. Things here in Katy’s flat are awful. There are rats running around even in the daytime. The pest control man said they are coming up under the shower base in the bathroom. He has put poison boxes down. I saw a poisoned rat coming out into the bathroom and I put it down the toilet. Katy has seen a rat running over the beds. The flat is very damp and humid and there are cockroaches everywhere. There is a drip leak over Mandy’s bed from the flat above. Every day, when I come, her bed is wet, and I have to change all the bedclothes. We both ring Migrant Help all the time, but they never get the Mears repairmen here.

‘Katy is very disabled, with very limited mobility and she can barely use her hands and cannot write. Katy has had four strokes and has epilepsy. She has hepatitis B and kidney problems and attends the outpatient department at Northern General hospital in Sheffield. Katy’s daughter Mandy has really severe asthma with regular attacks. The family are shielding because they are in the very high-risk category.’ With Katy’s permission, Pamela sent me a copy of a letter they had received which said that both Mandy and her mother are regarded by the government as ‘extremely clinically vulnerable’ to the Covid-19 virus and advised both of them to ‘shield’ during lockdown. ‘The safest course of action is that you should stay at home at all times and avoid any contact with anyone outside your household for at least twelve weeks.’

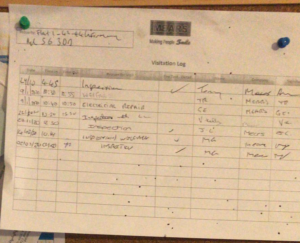

I asked Pamela to send me a copy of the management sheet in the flat, which Mears has in all their properties to record staff visits. It showed an inspection on 2 March, then nothing. I asked Katy (via Pamela) whether anyone had rung from Mears since. ‘No, nobody, I have rung and rung Migrant Help and eventually I got a pest control man here for the rats and cockroaches. Nobody from Mears has ever checked on how me and Mandy were.’

John Taylor, chief operating officer for Mears, answering questions from Home Affairs Select Committee about the company’s contact with vulnerable tenants during the Covid-19 lockdown, claimed that ‘we phone service users once a week to make sure they are okay’.[2]

Pamela had asked Katy about living as an asylum seeker in the UK. ‘She told me that she had been here for sixteen years. She had been sent all over, London, Cardiff and other places. She has been in her Sheffield flat for seven years. We have been looking after her for the past three years.’ When I checked with Pamela a few days later, Mears workers had come and replaced and sealed the shower base. A repairman who came for the leak over Mandy’s bed simply checked it and went away again saying he would come back. The Mears housing officer finally made contact with Katy, and told Pamela, ‘I don’t know why they are in this flat and have been here for seven years. This is meant for short stays only.’

Abandoned in an illegally rented flat

‘No, nobody from Mears came here since December.’ I was speaking with Raymond, a young Latin American man who had been living in a tiny asylum flat in a Barnsley basement with his partner April since November 2019. A few days before, the couple had had a baby daughter. Raymond proudly showed me a picture of his new daughter on his phone. Mother and daughter had returned to hospital to recover from the after-effects of a C-section birth.

A SYMAAG member and friend had met the couple and had seen where they were living. He asked me to go and see the basement flat, ‘It’s so small John, I don’t know how they will manage there with a new baby.’ When we arrived at the flat I started looking round. Raymond showed me the family’s bed

A SYMAAG member and friend had met the couple and had seen where they were living. He asked me to go and see the basement flat, ‘It’s so small John, I don’t know how they will manage there with a new baby.’ When we arrived at the flat I started looking round. Raymond showed me the family’s bed room. ‘Very hot in here,’ Raymond said. ‘This small window can open just a little.’ I had walked through the kitchen/lounge to enter the bedroom. It was clear that if there were to be a fire in the kitchen, the couple, and now their new baby, would have no way out through that tiny window.

room. ‘Very hot in here,’ Raymond said. ‘This small window can open just a little.’ I had walked through the kitchen/lounge to enter the bedroom. It was clear that if there were to be a fire in the kitchen, the couple, and now their new baby, would have no way out through that tiny window.

The flat had been illegally rented by Mears; the bedroom had no safe ‘egress’ to escape through. We went round to the rear of the building to look at the window from the outside. It was at the bottom of a railed-in shaft with no way out. My SYMAAG friend took a photo. ‘It must be ten foot down that shaft John, no ladders, nothing.’

No Mears contact since December

Raymond showed me the management sheet. ‘We came here 18 November 2019. Mears came twice to inspect. The last time they came here was on 16 December, they have never called us.’ So for the last five months of April’s pregnancy through Covid-19 lockdown, no inspections, no check on a vulnerable tenant.

Raymond showed me the management sheet. ‘We came here 18 November 2019. Mears came twice to inspect. The last time they came here was on 16 December, they have never called us.’ So for the last five months of April’s pregnancy through Covid-19 lockdown, no inspections, no check on a vulnerable tenant.

I asked Raymond whether Mears had sent them anything about Covid-19. ‘No, nothing, we were given no information.’ On 28 March, Mears had issued a statement to the Independent saying that the company ‘has ensured that all service users have translated guidance on how to respond to Covid-19 and what is required of them’.

Barnsley Council intervenes

I contacted Mears and Migrant Help that evening and copied in local councillors. The next day two council staff visited the flat. They must have threatened to serve an enforcement order on Mears to vacate the flat, because my SYMAAG friend rang me the next day to say ‘The Mears welfare officer has been sent to the flat and she says there is a flat very near which the family can move to.’

Then a couple of hours later he rang me. ‘Mears have cancelled the move. Raymond, April and the baby have been packed and kept waiting till 8.30 tonight. Now the driver says they have to go to Huddersfield. It’s 15 miles away from the hospital and their friends. They say they cannot go. April is still bleeding from the C-section and she refuses to travel with a baby only a few days old.’

Mears have the Home Office transport contracts as well as the asylum housing contracts, and should have known that the Home Office does not allow transport of newborn babies under six weeks.

When I checked again (on 10 June), the couple and their baby were still in the basement flat.

Asylum seekers at very high risk

On 7 May the Office for National Statistics announced that Black British people were twice as likely to die from Covid-19 as white people. Other ethnic minority people had an increased risk of between 30 and 80 percent. The vast majority of people in the asylum system and asylum accommodation in houses, hotels or Urban House are in these categories.

All my research alongside people in asylum accommodation has been carried out in the Mears contract area of Yorkshire and the north-east of England. On 15 May the Guardian reported that there were important regional differences in transmission rates of Covid-19, with transmission rates in the north-east and Yorkshire twice those in London.

Both in terms of ethnicity and in terms of their geographical location, the asylum seekers I see are at very high risk from Covid-19, which makes the conditions they live in even more worrying.

All names have been changed in this article.