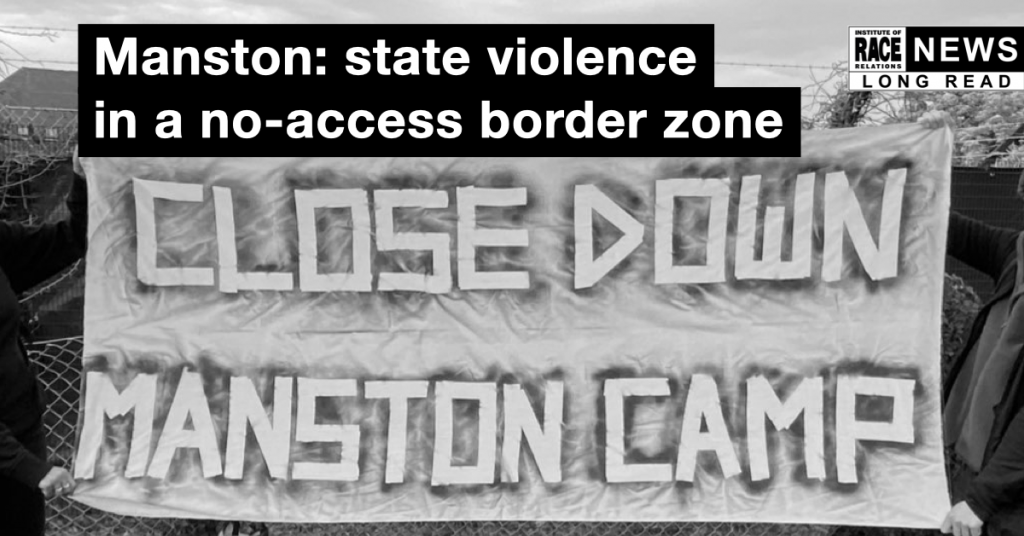

The Manston camp has been emptied following the death of a man who was detained there. But this will not put an end to the humanitarian crisis facing newly arrived migrants and refugees, which is caused by policies of criminalisation and deterrence.

Since February, an isolated former RAF base near the village of Manston, in Kent, has been used by the Home Office to warehouse migrants reaching England’s southeastern shores on small boats. These are desperate people fleeing conflict, persecution, immiseration, environmental degradation and other crises. Most of them claim asylum. They all deserve better. Their ordeal – prolonged detention in absolute squalor, with no recourse to legal remedies nor contact with the outside world – has rightly been called a ‘humanitarian crisis’.

But it is equally a ‘politically manufactured crisis’: the foreseeable result of government decision-making and policy towards the vast majority of the global poor, who are unable to access the vaunted but practically non-existent ‘safe and legal routes’ to the UK. They are being punished for refusing to suffer quietly and for daring to seek safety, improved living standards, and family reunion. ‘The reception and treatment of those making the Channel crossing is the worst it has ever been’, IRR Vice-Chair Frances Webber wrote at the beginning of the year. With the passing of the Nationality and Borders Act – enshrining former home secretary Priti Patel’s Fortress Britain vision in law – and the agreement of the torturous Rwanda scheme, the situation has deteriorated further, compounded by an enormous backlog in the asylum system. Only a year ago, at least 27 people drowned in the Channel, the victims of non-assistance by British and French authorities. Last weekend, a man died after his health deteriorated over the course of a week at Manston. It was only a matter of time before the worst happened – but that does not lessen the sadness and the rage. To the question asked by journalist Daniel Trilling, ‘what level of violence are you prepared to tolerate to keep people in their place?’, this government and its supporters have answered: any.

‘We need your help’

I visited Manston on Sunday 30 October alongside fellow activists from SOAS Detainee Support (SDS) and other members of Action Against Detention and Deportations (a UK-wide network of border abolitionist groups). Of the conditions inside we knew only what little had so far trickled out in the media – enough to prompt deep alarm. Authorities with access had decried them as utterly wretched and inhumane. The Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration (ICIBI) found himself ‘speechless’ and ‘without any frame of reference’ after visiting earlier in the week.[1] A detained population of 3,000 was widely reported in the days before our visit – far greater than any existing prison or detention facility in the UK. This despite an ‘intended’ capacity of 1,000 and an upper limit of 1,600 in ‘exceptional circumstances’. (According to a Home Office source, management of the camp actually ‘starts to collapse at 400’). Some people, including families with children, had reportedly languished there for over a month, contradicting ministers’ claims that it would be used for brief stays of 24-48 hours for initial ‘processing’. Overcrowding and poor sanitation were also proving fertile ground for the spread of infectious diseases such as diphtheria, which can have a case-fatality rate of up to 20 per cent in under-fives.

With notable exceptions, journalists had neglected their duties at Manston – few, it seemed, had actually bothered to visit the site. So we decided to investigate ourselves, aiming above all to make contact and show solidarity with people inside, whose voices were nowhere to be found in media coverage. Their absence was easily explained, of course: then as now, detainees’ phones are confiscated on, if not before, arrival at the camp; NGOs and charities are barred; and attempts to establish local visiting groups have, to my knowledge, been rebuffed or ignored.

On our arrival at one of the camp’s barbed wire perimeter fences, dozens of young children ran towards us with cries of ‘freedom’ and ‘we need your help’. Through a megaphone we asked questions to a large crowd in the distance who were kept back by private security: they shouted to us that they were from all over – Afghanistan, Iran, Syria, Sudan, Pakistan; that conditions were poor and some of them were sick; and that some had been there for up to 40 days. It was impossible for us to estimate numbers – the camp was too vast. However, local MP Roger Gale, who drove past us into Manston, said 4,000 were being held at the time, after new boat arrivals and an exodus from the Dover processing centre hit by a far-right petrol bomb attack. In just two or three hours we saw 13 coaches arrive full of people wrapped in space blankets, and almost none leave. Our report of what we witnessed circulated widely on social media and major news platforms, eliciting widespread public anger at such stark mistreatment. One photo, of a man holding his daughter’s hand, penned in by fences, was particularly powerful. The government, Victoria Canning argues, is adept at creating a spectacle out of small boat arrivals ‘in a way that encourages the public to equate “migrant” with “illegal”’. But they were losing control of the narrative here. These were humans in cages, begging for help. What, these images and videos insisted, are you prepared to tolerate?

A culture of violence, abuse and neglect

With increased public scrutiny of Manston came new revelations from inside. Undercover whistleblower footage visualised what we could only imagine from outside: people sleeping chock-a-block on mats on the wooden floors of unheated marquees. Given the secretive and highly securitised nature of the camp – where private contractors such as Mitie and MTC work alongside Home Office officials, prison officers and military personnel – there are probably many horror stories yet to be uncovered and litigated. A detainee was violently dragged out of reach recently when attempting to speak to journalists across the fences. Some disturbing insights can be gleaned from an anonymous account by a Manston ‘security manager’. He describes an atmosphere of pervasive despair – people ‘wailing and screaming’ for help, and using anything to hand as a weapon or self-harm instrument. The worst thing you can do, in his view, is to tell detainees the time, because that enables them ‘to coordinate protests between the different tents’. Yet protesting, according to one former detainee, was the only way to get medical attention for someone who collapsed. And we know that brute force has been used to break up at least one peaceful sit-in protest.

Manston is the kind of no-access border zone where a culture of violence, abuse and neglect can thrive with impunity. Untrained and unvetted staff [2] have authority over vulnerable people and children who are identified not by names but by wristband numbers – ‘“cases” not “faces”’, to quote the ICIBI in another context.[3] It is a safeguarding vacuum. Child asylum seekers have alleged that screening officials told them they could leave the site quicker if they said they were adults. Another example of malpractice involved private security trying to sell drugs to detainees. Concerns have also been raised that Albanians removed on two ‘zero notice’ flights under the fast-track agreement signed in August 2022 were denied access to the asylum process while held at Manston.[4]

The framework of war

SDS and the direct action group Stop Deportations both described Manston as a ‘concentration camp’. Many others followed suit. This was not intended as a Holocaust analogy, although it is important to note that a group of Holocaust survivors wrote an open letter to home secretary Suella Braverman warning her about the potential consequences of her dehumanising language. In the summer of 2019, progressive congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez accused the United States government of ‘running concentration camps on our southern border’, emphasising: ‘and that is exactly what they are’. Some republicans accused her, in turn, of Holocaust trivialisation for inviting comparisons between immigration detention centres and Nazi death camps. The latter remain historically incomparable: the industrial machinery for the genocidal extermination of persecuted groups – Jews, Roma and other ‘Untermenschen’ – at a speed and scale not seen before or since. Ocasio-Cortez certainly intended to invoke the Holocaust, but less for the purpose of equivalence and more as a warning, in the manner of the survivors writing to Braverman. In follow-up statements, Ocasio-Cortez cited a broader, historically-rooted and scholarly definition of concentration camps, one that evokes its pre- and post-Holocaust usage for the mass detention of civilians without trial. Historically, this has usually involved, as genocide scholar Zoé Samudzi explains, ‘the creation of material conditions that tend to lead to premature death’, whether through malnourishment, disease or overwork, if not outright physical violence. These spaces were pioneered in the early twentieth-century by Spain (in Cuba), the U.S. (in the Philippines), Wilhelmine Germany (in what is now called Namibia) – and by Britain, notably during the Second Boer War and subsequently in other colonial contexts. This is why Neil Mackay’s lament that ‘We’re becoming America…’, in an otherwise excellent article on Manston, is misplaced. Manston can be situated in a longer history of British practices of racialised detention. It is not, that is to say, without national precedent.

In her global history of concentration camps, Andrea Pitzer writes that their use indicates ‘a deliberate choice to inject the framework of war into society itself’.[5] And in modern warfare, almost anything is permitted in order to defeat an enemy considered less than human. Since their significant increase in 2019, Channel crossings have been portrayed, with varying degrees of vulgarity, as a siege on the territorially bounded British nation-state. The appointment of a former Royal Marine to the ominously titled position of ‘Clandestine Channel Threat Commander’ in August 2020 was emblematic of an increasingly militarised approach. As were proposals – fortunately abandoned after legal challenges – for pushbacks at sea, a tactic which has proved so deadly in the Aegean. The Manston regime has been conceived with a similar military mindset. Lieutenant General Stuart Skeates, who served in Afghanistan, was seconded to the Home Office in late October to establish a ‘command and control’ structure at the camp. Braverman is an unabashed advocate of the framework of war, vociferating against a Channel ‘invasion’ only a day after the Dover attack, which was inspired by exactly that kind of rhetoric. In a farcical show of strength a few days later, she flew to Manston in a military Chinook helicopter. The media are responsible for creating this atmosphere too. In a representative case, BBC Kent reporter Michael Keohan described the port of Dover as an area where ‘the UK is defending itself on the frontline against migrants’. In response to criticism, he claimed only to be ventriloquising the legitimate concerns of local people. However, this is precisely the problem with much of the media: it ideologically reinforces state racism by presenting it as the the common-sense ‘legitimate concerns’ of a homogeneous ‘ordinary people’ (read: white Britons). A pernicious consequence of this is the fillip given to racism in the localities to which asylum seekers are dispersed, often with no support networks for self-defence. The Tory MP for Stoke made the absurd claim that people are crossing the Channel ‘for no reason’ before naming a hotel housing asylum seekers in his constituency, leaving residents vulnerable to far-right harassment and increasing the risk of another Dover-style attack.[6] The Refugee Council has written to the House of Commons speaker requesting that Tory MPs follow Home Office practice and refrain from naming hotels, but several have vowed to continue.

Ignoring warnings, flouting laws

There was scant reporting on Manston between its opening in February and the Prison Officers’ Association’s warning, in early October, that it was becoming a ‘pressure cooker’ for unrest. But the ‘crisis’ at Manston was foreseen by some in advance of its opening. The executive decision to convert the site into a migrant centre was made in December last year without consulting local representatives or migrant support organisations. In the Commons, Gale criticised the ‘dog-whistle proposal’ to hold people in ‘largely unsuitable conditions, simply to satisfy a perceived demand that can, and should, be met by other means’. Jeremy Corbyn warned of a ‘repeat of the appalling behaviour of the Home Office over Napier barracks’.

A July report by HM Chief Inspector of Prisons on short-term holding facilities (STHFs), including Manston, catalogued problems that would intensify over the following months – from long detention times to chronic safeguarding issues, as well as various indignities such as men not being allowed to close toilet doors in the screening interview building. It seems that no action was taken by October, when the population began to increase significantly. Indeed, there is evidence that the home secretary actively obstructed workable short-term alternatives by refusing to sign off on bookings in hotels, allegedly because they were in Tory areas. In the latest example of ministerial contempt for the rule of law – limited though such a notion is in the context of a government that wields the law as an instrument of repression – she also ignored several pieces of official advice warning that Manston was operating unlawfully, a charge that one minister has since conceded.

Exactly what type of STHF the government intended Manston to be, in a technical legal sense, is not very clear. STHFs are used to hold people briefly before removal or after arrival while the immigration authorities decide what to do next. By law, ‘residential’ STHFs can hold people for up to seven days, while ‘non-residential’ STHFs (‘holding rooms’) can hold people for 24 hours, extendable on review by a further day in ‘exceptional circumstances’. Holding rooms are circularly defined as any place where a person ‘may be detained for a period of not more than 24 hours unless a longer period is authorised’. Minimum standards – in relation to food, hygiene, accommodation and other basics – apply to residential STHFs but not to holding rooms. Given that large parts of Manston, by all accounts, appear to be completely unfit for human habitation, and that people have been held for longer than 24 hours, it makes sense that Detention Action is arguing that detention is unlawful beyond 24 hours. Bail for Immigration Detainees is also bringing a challenge for breaches of the rules regarding access to phones and to legal guidance, including information about the immigration bail process. The number of potential compensation claims for unlawful detention could be in the thousands.

Braverman has been the primary focus of public scrutiny, but these tendencies – ignoring warnings, flouting laws – are endemic to the Home Office, whose priorities are shaped by the political imperative of combating immigration, however much violence is required in the process. The decision to hold people in dismal ex-military settings is driven by ministers’ concerns that housing asylum seekers anywhere remotely decent will ‘undermine public confidence’ in the immigration system. This is a reference to right-wing voters, not the public at large, many of whom do not want to see vulnerable people treated with such inhumanity.

Answering questions about Manston before it opened, then immigration minister Tom Pursglove said that the site ‘will provide safe and secure accommodation for illegal migrants whilst the government carries out necessary checks.’ There is a perfunctory reference to standards here. But the accent is on ‘illegal’, with all that implies: that these people are here illegitimately and therefore deserve whatever they get. This attitude underlies policing (and former immigration compliance) minister Chris Philp’s comment that ‘it’s a bit of a cheek’ for migrants to complain about conditions at Manston, and Scott Benton MP’s peremptory dismissal of the ‘ridiculous narrative of economic migrants somehow being mistreated’. It is also evident in the way the Home Office interacts with the judicial process, as revealed in a recent High Court judgment in the Channel crossings phone seizures case. The Home Office misinformed government lawyers that a blanket policy to search, seize and extract data from phones belonging to new boat arrivals had been abandoned by the time the legal challenge was brought, and then left them to argue, on the basis of that falsehood, that no such policy ever existed – a clear failure of the ‘duty of candour’.[7]

The detention archipelago

Manston is one manifestation of the ongoing huge carceral expansion of the hostile environment against migrants: an archipelago of detention and ‘quasi-detention’ sites where, as Sophie Cartwright argues, ‘the rules and powers at play are increasingly unclear’. The government intends for these places to act as a deterrent to people crossing the Channel. Patel’s New Plan for Immigration, published in March 2021, signalled the government’s intention to shift away from accommodating asylum seekers in the community to segregating them in ‘asylum reception centres’ which ‘provide basic accommodation’. The dilapidated Napier and Penally barracks, opened in September 2020 as ‘contingency asylum accommodation’, piloted this new model, and demonstrated what the government meant by ‘basic’. The High Court found that Napier fell below the minimum standards for asylum reception and, in the words of a former resident, felt ‘like a detention centre or prison camp’.[8] Penally was closed in March 2021 after a damning joint inspection by the prison and border inspectorates, but Napier remains open. Another example of this new model was the planned construction, adjacent to the existing Yarl’s Wood immigration removal centre (IRC), of a 187-bed facility for asylum seekers. Described by a local councillor as ‘like a prisoner of war camp’, it was fortunately aborted in February 2021 under threat of legal action. The New Plan also pledged to end the use of hotels, which the Right sees as too generous for asylum seekers. The reality is, of course, brutally different, and use of hotels is unlikely to end any time soon. An investigation by the Independent and Liberty Investigates found some asylum seekers living in hotels in conditions that amounted to ‘effective detention’. A new report by the Medact Migrant Solidarity Group finds that across all forms of contingency accommodation people are ‘struggling to meet basic needs such as access to nutritious food and access to legal and other services, facing barriers to healthcare registration, movement restriction and frequent moves, and being transferred at short notice.’[9] The suffering of people in hotels serves as a reminder that ‘deprivation of liberty might take a variety of forms other than classic detention in prison or strict arrest’.[10] Indeed, even so-called ‘alternatives to detention’ such as GPS tags – imposed as a condition of immigration bail since August 2021 – are experienced, Lucie Audibert and Monish Bhatia argue, as ‘a punishment and deprivation of liberty’.

Alongside the trend towards quasi-detention are several plans to expand the official immigration detention centre estate after years of falling detention numbers. Haslar IRC (closed in 2015) near Portsmouth and Campsfield House IRC (closed in 2019) near Oxford are both slated to reopen in the near future. The Home Office has also informed visitor groups of plans to open a new women’s unit at Yarl’s Wood – which became a predominantly male STHF in August 2020 – and a new residential STHF in Swinderby, Lincolnshire. The brief period during the pandemic when detention centres were emptied – not entirely, as in Spain, but partially – seems far away now. This reversal of direction is inextricable from the two-tier asylum regime introduced by the Nationality and Borders Act, which expands the detainable and deportable population by rendering all asylum seekers who arrive ‘irregularly’ on small boats liable for removal to any ‘safe third country’ that will take them. If nowhere will take them and they are recognised as refugees in the UK, they will only be given temporary permission to stay for 30 months, with limited family reunion and welfare rights – and the ever-present threat of removal.

What solution?

The government and large parts of the media have framed Manston as a problem of sheer numbers crossing the Channel, attempting to ‘game’ the system, and thereby straining state resources. The proposed solution, as ever, is to make the sea route ‘unviable’ through increased border policing and removals. A new €72 million agreement with France was signed to that effect earlier this month. As the IRR argued in its report on militarisation and deaths in the Channel, ‘these actions will not stop people trying to reach Britain, but will instead force them to try even more dangerous methods – crossing at night, or longer, less-travelled routes.’[11] Keir Starmer’s right-wing Labour party, though less demagogic on immigration, appears happy to campaign on this terrain, with shadow home secretary Yvette Cooper vowing to ‘crack down’ more effectively on Channel crossings and shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves calling for more deportations.

The main barriers to a more humane approach are political will and ideology, not finite state resources. The UK is a wealthy country, receives a relatively small number of people seeking safety by international standards, and spends millions each day on needless authoritarian responses. With the party of government controlled by hard-right nativists and an official opposition implacably hostile to its former left-wing base, there is little hope that either will fundamentally change course on borders any time soon. Borders and xeno-racism are, after all, useful tools for capitalist governance: they cohere fragmented voting blocs around opposition to minority ‘others’, even as living standards for most people tank; they segment, divide and weaken workers, making exploitation easier and organised counter-power harder; and they hoard national wealth away from those who have a rightful claim to it in light of histories of colonial entanglement and an unequal international division of labour.

The furore over Manston has shown how powerful organised interventions from the radical grassroots can be even in the context of a pro-borders consensus in mainstream politics. On Saturday 5 November, hundreds of people – a mixture of Thanet locals and people from London and elsewhere – braved torrential rain to protest outside the camp. Their demands were clear: shut it down and welcome people crossing the Channel by providing the resources – housing, education and work – they need to build new and flourishing lives. Communities, not camps. Under formidable pressure from below, the Home Office swiftly reduced the population in the camp from 4,000 to 1,600. But this is not the end of the story. While preferable to Manston, many were dispersed to other types of inadequate ‘contingency accommodation’, mostly hotels. Some have been left street homeless, while others may be in detention centres. Moreover, the first death of someone detained at Manston shows that prevailing conditions did not substantially change as a result of the reduction in numbers. Reports suggest that after an initial stay in hospital the man – currently unidentified – was discharged to Manston, where his health significantly deteriorated. He was then kept for several days in a ‘medical bay’ at the camp before being returned to a hospital the day before he died. By which point it was possibly too late. Whether it’s 4,000 or 1,600 people inside, then, Manston is no place for human beings. As Sivanandan said, one death is a death too many.

As I finished writing this piece, reports emerged that Manston has been completely emptied. This is welcome news, and represents an initial defeat for Braverman. But concerns remain over where these thousands of people are being taken and what support they are receiving. A similar humanitarian crisis is also likely to occur if ministers realise plans to press other redundant military bases or unused holiday camps into service. And as happened at Napier in April 2021, the home secretary could fill Manston up again if she chooses, arguing that sufficient ‘improvements’ have been made in response to criticism and legal challenges. The fight must therefore continue for the camp to be decommissioned entirely, along with the rest of the hostile environment and its border cages.