IRR’s Sophia Siddiqui has a discussion with Amrit Wilson, an activist and writer, whose seminal book Finding a Voice: struggles of South Asian women has just been republished, forty years later.

Why did you write the book in 1978 and why is it relevant today?

Back in the 70s like many other community activists and South Asian feminists, I had become aware that our communities were being seen through a very colonial anthropological lens. Because race and gender are so intertwined there was a particular interest in women. A growing number of academics were becoming ‘experts’ by studying and objectifying us. They would gather material by meeting Asian women, and speaking to them, often via their husbands, and then come up with theories which were implicitly racist – that Asian women were ‘passive’, for example, or to that we have low ‘pain thresholds’, poor mothering skills and so on. What was worse was that often these stereotypes were used to justify government policies.

Many of us felt that a book in which Asian women could set the record straight was needed and because I was at the time a freelance journalist people suggested that I think of writing a book. Around the same time I was also offered a contract by Virago, the first feminist publishers in this country – so that is how Finding a Voice came to be written.

Many of us felt that a book in which Asian women could set the record straight was needed and because I was at the time a freelance journalist people suggested that I think of writing a book. Around the same time I was also offered a contract by Virago, the first feminist publishers in this country – so that is how Finding a Voice came to be written.

Actually writing it was not easy though because we were constantly told that South Asian patriarchy was something exceptionally violent and barbaric, or that patriarchy itself was something that had been imported from all those countries Britain had tried to ‘civilise’. To counter this I tried to write about the reality of women’s everyday lives, what we faced at home and the battles we fought at work and also how we felt and what we thought. How our experience of race (and class) is inevitably gendered while the patriarchy we face is shaped by race and class.

But conceptualising the book was not easy. In the end my conversations with many of the women made me realise that through these varied voices and individual experiences, feelings, and ideas I had to portray a collective experience. It was very difficult to begin writing but it was also very exciting because I felt I was doing something which had not been done before.

How did you find the women that you interviewed?

My activism and my journalism were very much connected. People would call me up and tell me about racist attacks. I remember I went to Coventry, where at the time there was a lot of racial violence. I went there and, of course, I was met at the station by a group of men and taken to a pub to speak with them. When they had told me what they wanted to I asked to see the women in their families. This was considered very strange and I remember them saying things like ‘why do you want to meet my wife, she doesn’t know anything’.

I found my conversations with women gave me a far deeper understanding of situations. Sometimes people would ring me up and tell me about impending deportations, they would ask me to write about them because publicity might help the case and again I found talking to women essential. Occasionally women I had got to know would call me and say that I should interview particular social workers who had been incredibly racist to them. Because of all this, even before I started writing the book I had got to know a large number of women in different South Asian communities. And once I started writing I had the support of many progressive community workers and teachers and others, both South Asian and white. They helped me enormously by introducing me to others they thought I should meet.

In the 70s and early 80s, South Asians in this country were friendlier to each other, more open to each other. There were fewer divisions amongst us. In fact, one of my most powerful narrators in the book was a woman I met by chance one day when I got lost in East London. I asked her in Hindi if she could direct me to the nearest tube station. She couldn’t, but she invited me into her house to look at her A-Z. And then we got talking, I told her that I was writing a book and she said she wanted to tell me about her life. I can never forget the way she told her story and the need she felt to do so. I remember she offered me some food and there was a very hot chutney – it was so nice but so hot. And then suddenly we were both crying, I don’t know if it was the chillies… She told me so much. She was the one who ultimately pushed me to begin writing the book.

How has the South Asian community changed? When reading the book, I felt that we don’t have this enveloping South Asian community, it feels much more fragmented now.

The South Asian communities today are fragmented. Multicultural and later multi-faith policies in the local and national state created huge divisions by offering us funds according to nationality, language and religion, and from the 1990s on, the British state’s own rampant Islamophobia encouraged religious divisions in the South Asian communities. Also there was, particularly from the 1990s on, the growth of the religious right in our countries of origin, particularly Hindu supremacy in India and this has been replicated in our communities here, causing deep divisions.

But to return to multiculturalism, many people tend to see the era of multicultural policies as some kind of golden age – I don’t agree. While it did have positive aspects it did not recognise the differences of gender, caste or class. If anything, it heightened women’s oppression because it gave power to a host of very patriarchal community leaders who were willing to do the state’s bidding. And across the board it encouraged the most reactionary sections of our communities, the right-wing, Islamophobic and casteist Hindu organisations, for example.

Are there particular challenges when writing about your own community, did you for example get accused of attaching blame to your own community?

For me and for all those of us who come from a Marxist position, oppression has to be located within certain structures. If you centre a woman in your writing, then you have to see the different forces that have affected her – both historically as well as in the present. And those forces can be anything from colonialism, to the class she comes from, to the racism she faces, to the type of patriarchy which has been, and is, oppressing her. Once you see the structures and the way they interact, then the nature of oppression becomes clearer, and victim-blaming is exposed for what it is.

The past

I wanted to now discuss what has changed since you published Finding a Voice forty years ago, and what has stayed the same. Continuities between the book and the present day were depressing to read, for instance, the same detention centres mentioned in your book exist today. Have things just become even worse, particularly in terms of immigration?

Yes, one can feel very depressed by today’s horrific scale of deportations of people who have spent their lives in Britain, by the rapes, violence and suicides in detention centres, by the hostile environment policy, the massive criminalisation of Black people and Muslims, and much else in this country…. But, in fact, the late 70s was the period when the foundations of the authoritarian state were being laid. A lot of what’s happening now can be traced back to that period – mass surveillance, terrorism laws and even police methods like kettling. The difference now is that we have a neoliberal state, public services are almost entirely privatised, big business, corporates have almost total power and the freedom to destroy lives in the interests of profit is complete. For example, G4S and Serco and other corporates now literally control the detention centres. At the same time capitalism now demands war, and endless war brings endless profits, and so countries are destroyed, people are killed in huge numbers or lose their homes and livelihoods and are forced to flee and become refugees. At the same time, in an enormous irony, we are being told that we as individuals have never had it so good, because we have choices of all kinds.

In the introduction you write ‘if we can remember our rich collective past, we will find ourselves stronger in battles ahead’. Why is it important to remember historical struggles?

If we do not know our history we become rootless. These days people often talk of legacies, role models and wisdom, but I don’t know how useful those approaches are. I think it’s more useful to look at the past, and see the struggles which have been fought, how the present came to be the way it is so that we are more able to fight for the future we want.

Violence Against Women and Girls

To get to the specifics, I’d like to talk about your work in the Violence against Women and Girls (VAWG) movement. Can you tell me about how you set up the first Asian women’s refuge in the UK, and why we need such provision?

Those of us who set up Awaz [the first feminist Asian women’s collective in the UK, whose name means ‘sound’ in Urdu] had noticed that VAWG was such a huge issue in our communities and that there was no provision at all for support. But to even begin the process of establishing a refuge we had to do a lot of work, to convince councils and other local and national agencies that we needed provision for Asian women, because their attitude at the time was, ‘Why do we need something separate for women, and then again why for South Asian women?’ We had to explain that traumatised women and children not only need familiar food and kitchen arrangements but safe spaces free of racism. Explaining this was not easy because many of the white people in positions of power whom we spoke to immediately assumed that we were accusing them of racism – and being accused of racism was considered far worse than facing racism.

But ultimately we succeeded and set up the first Asian women’s refuge in London, the Asha refuge which still exists. By the 90s and even the early 2000s, we had an amazing network of refuges and services for South Asian women. There were not enough of them, but many of those that existed provided so much that was needed – facilities for mental health counselling, help with immigration cases, outreach work which was a lifeline for women trapped in their homes, and a whole host of provisions which had been improved through experiences over the years. Now so many of these specialist refuges and services have had to close because of cuts in funding or they have had to merge with large generic organisations which do not have the understanding of racism or the expertise to cater to the needs of women of colour.

Those battles which we fought back in the 70s and 90s to establish the need for special provision for women of colour are sadly having to be fought again. Apna Haq [a support service for BAME women to escape and overcome domestic and sexual violence in Rotherham], for example, had their grant taken away and given to a generic organisation. Apna Haq was told they were not any use, but now they have fought back and they have got some funding. It was a very inspiring struggle because although it was mainly women of Pakistani origin who used the service, those who helped in their struggle for funds included many other women of colour – Chinese women, African women and others. Zlakha Ahmed, who set up Apna Haq, has described these struggles in the new chapter ‘In conversation with Finding a Voice: 40 years on’.

What were the difficulties of writing about domestic violence – especially with continued racialised depictions about violence against Asian women, ‘honour killings’ and tropes of ‘white men saving brown women from brown men’?

Patriarchy is systemic and exists in all societies, and if we remember that, it makes it far easier to understand and speak about violence against women in different communities. When we assume that patriarchy is something imported it is essentially a racist assumption. Many Black feminists in the VAWG movement have pointed out that what terms like ‘Honour Killings’ or ‘Honour Crimes’ do is simply exoticise domestic violence. Women facing violence do not exist simply in the context of the patriarchy they face from their families, they also exist in the wider world with all the other structures of oppression. It is interesting, for example, that one of the films being used by state agencies in the context of these so-called ‘Honour killings’ is a film ‘Honour Diaries’ that is supported by anti-Muslim groups and right-wing NGOs.

For all these reasons we must continue to speak out about violence women face. Silence cannot take us anywhere. As Audre Lorde has said, as so many others have said, we have to speak. That is the essence of Black feminism: we will not be silenced, about anything. And we will locate our experiences within a broader framework.

Unity across communities and generations

How did women of colour unite against colonialism and imperialism under the term Black, and why is unity between women’s struggles important?

When OWAAD [the Organisation of Women of Asian and African descent, an umbrella organisation that campaigned from 1978-1982 on issues including immigration, domestic violence and policing] was formed, Awaz joined as a member organisation. We co-organised a massive national demonstration against state brutality with Brixton Black Women’s Group and the Indian Workers’ Association GB. Also in 1989, Awaz organised a powerful demonstration at Heathrow against the ‘Virginity Tests’ of would-be South Asian fiancées, and later a sit-in with our sisters from OWAAD.

Today, there is still a real need for solidarity between people like us of South Asian origin and people of African origin – not only because of our history of imperialist exploitation but because of what is happening now and also, of course, because the racism we face in Britain hasn’t gone away. I am not suggesting a merging of identities, rather the finding of commonalities and solidarities in struggles.

Looking at the economic aspects of imperialism in a broader context we can see that Africa is being looted as never before by global multi-national companies; the same thing is happening in the central belt of India, where minerals and metals are to be found under the earth, people are being displaced by mining corporates, and those who resist are being brutally murdered with the help of the state. These struggles are taking place in these two parts of the world, and we are here, linked to both of them. So while, of course, we need to confront anti-African and anti-Black racism in our own South Asian communities, unity is still possible because unity is created by us and by how we organise.

Why does a sense of sisterhood make us stronger?

Sisterhood of women of colour breaks our isolation as we realise that neither are we alone, nor are the struggles and oppression we face unique to us. I think that’s a very liberating experience in a neoliberal society which is so very focussed on the individual that blaming ourselves becomes easy.

The same types of struggles are still going on today, although in a different terrain. [The Grunwick strike in 1976-8 connects to the current struggles of migrant workers, a connection Sujata Aurora makes in the new chapter of Finding a Voice.] Some of those battles are being won, which is very inspiring. It is when women of colour come together to fight these battles that identities of struggle are created which are so important for us as political activists. What are we other than what our skin dictates? Have we got other aspects of us that perhaps also shape our identity – what we dream of, what we want, what we seek in the future for ourselves and for others?

In the final chapter to the new edition, young South Asian women describe what Finding a Voice means to them. What strikes you about those responses?

For me, the last chapter is the most exciting, because it shows the ways things have changed, up to a point, but also shows the ways struggles have continued, so in that sense it brings it full circle in a way which I could not have done. I was really quite bowled over, some of them were so moving, so powerful, so analytical.

Why is solidarity across generations important?

I’ve learnt so much from my mother, my daughter and my granddaughter and from so many other women young and old, that I wouldn’t be me without them. But on a more general level, I think to understand the oppression that a woman faces, and to understand how patriarchy functions, you need to understand the history of what has gone before. And you need to understand the dreams of the women that went before. To know them, to recall them, is so important.

Not all mothers and daughters are in the same position as me, of course, but whatever our relationship with mothers may be, it’s so important that we know the structures of oppression that they faced, what they wanted in their lives and why they wanted it, why perhaps, sometimes, they were unable to take a stand against patriarchal violence. I think those things are very important for us to become strong ourselves, to face the world.

So much has been achieved by women, we cannot ignore that fact – women’s lives have changed so much. And yet at the same time, in many ways it is harder for young women than it ever was. We need to examine these contradictions and our own histories.

The upheavals and pain which women of the earlier generation endured must be acknowledged, because otherwise it can create a silencing, which weakens us all, and the amazing struggles they waged and the victories they won need to be remembered and celebrated.

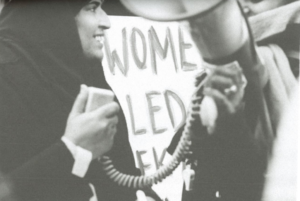

Black People Against State Brutality demonstration in 1979.

Related links

Finding a voice: Asian women in Britain (New and Expanded edition, 2018) is published by Daraja Press and is available to buy here.

‘Reclaiming our collective past’: Amrit Wilson reflects on 40 years of anti-racist feminist work