The coordinator of the IRR’s Black History Collection digs deep into the archive and shows how public opinion is constructed

For reasons that are deeply contradictory, the Caribbean community in Britain has been at the forefront in media and parliamentary debate this summer. Its contribution to British society was rightly highlighted and praised in the many 70th anniversary celebrations of the Empire Windrush exhibitions and talks. One of which, the exhibition at the British Library, was heavily informed by the Institute of Race Relations’ Black History Collection. But it was also revealed that the governments’ hostile environment immigration policies have led to unemployment, homelessness, deportation and even death amongst the Windrush generation, who, because of the Home Office’s relentless pursuit of ‘illegals’ were placed in the precarious position of having to ‘prove’ their status.

From Empire Windrush to the Notting Hill ‘race riots’

What t his summer and the celebrations of the Empire Windrush have shown is that there is much of the Caribbean British story that is known and just as much that is unknown. There have been articles exploring how the very term ‘Windrush’ has not been commonly used to describe the community until this year and this scandal. It has been known that the Empire Windrush docked in ’48 but it was unknown that Beryl Gilroy (mother of historian and cultural studies analyst Paul Gilroy) was the first black head teacher in London. Similarly, Notting Hill Carnival is famous, for right-wing commentators infamous, but how much today’s festival links to the horrendous events that gave birth to it is most usually absent from discussion, in the mainstream media at least.

his summer and the celebrations of the Empire Windrush have shown is that there is much of the Caribbean British story that is known and just as much that is unknown. There have been articles exploring how the very term ‘Windrush’ has not been commonly used to describe the community until this year and this scandal. It has been known that the Empire Windrush docked in ’48 but it was unknown that Beryl Gilroy (mother of historian and cultural studies analyst Paul Gilroy) was the first black head teacher in London. Similarly, Notting Hill Carnival is famous, for right-wing commentators infamous, but how much today’s festival links to the horrendous events that gave birth to it is most usually absent from discussion, in the mainstream media at least.

The Notting Hill riots occurred in London at the end of August 1958, just ten years after the Empire Windrush docked. The ‘riots’ occurred over a few weeks in a few streets in west London after self-styled ‘Teddy Boys’ attacked members of the newly settled West Indian community and although they weren’t the only riots to happen that summer, there were also riots in Nottingham, nor the first anti-black riots, they are certainly the ones that has gone down in history.

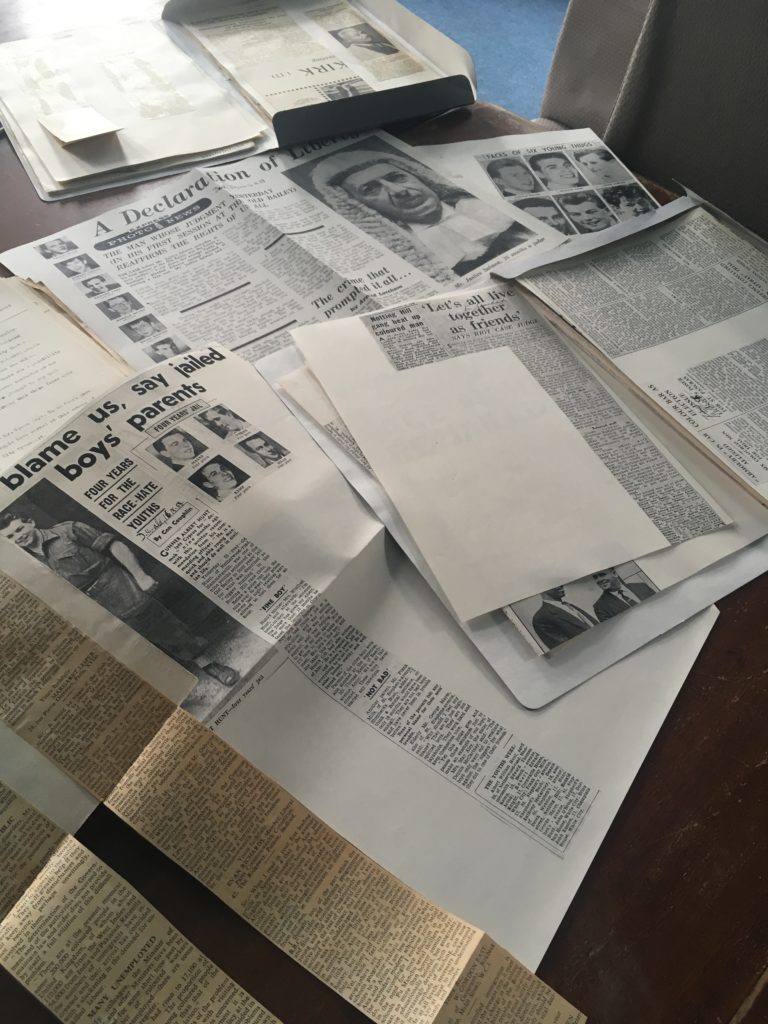

This history, the media representations of events at the time and community activism can all be seen in the Institute of Race Relations’ Black History Collection that has a unique collection of posters, leaflets, flyers, newspaper cuttings, campaign materials and more than 160 journals from black community and grassroots groups in the anti-racist struggle from the 1950s to 1980s.

Investigating mainstream media attitudes

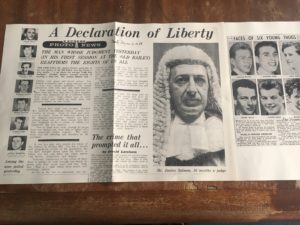

In here you can see newspaper cuttings from the days following the riots in both Notting Hill and Nottingham that occurred in late summer 1958 showing those who were arrested and charged as well as ‘public opinion’, or at least the mainstream media’s interpretation. There are articles from the Times on 25 August that speak of black men ‘running wild’ in Nottingham and attacking white couples returning from an evening out. In the article no black people have been interviewed. It is only white couples and predominantly white women and it is not until the end of the article that the hostility of the white population to the ‘many coloured people in the area’ is even mentioned.

There is also a short article in the same newspaper on 26 August that describes the charging of ‘nine young men’ in London with ‘unlawfully and maliciously wounding a coloured man with intent to cause grievous bodily harm’. No bail was set due to the serious injuries sustained by those they attacked. But this incident, which does not refer to the young perpetrators’ colour, is one that is remembered today as the acts of a group of white working class ‘Teddy Boys’ who went on a rampage, ‘n**ger hunting’ that evening. The reserve and restraint with which their actions are described in the Times goes a long way to showing the reader the common feelings in the immediate aftermath of events.

On the other hand, there are also newspaper clippings from the Daily Express and the News Chronicle that show mug shots of the white men charged with the violent attacks in Notting Hill, in which the Judge presiding over the case calls the actions ‘grave and brutal crimes’ and a ‘cruel and vicious manhunt’. At a time when society is beginning to re-examine itself, through the re-emergence of disregarded histories and sustained critical interrogation of the media, the Black History Collection and other such archives are so important. For they give the younger generation, my generation, an opportunity to discover what we didn’t know, see how things were and learn from them.