The Grenfell Tower inferno throws up all the contradictions between community self-help and resistance and an uncaring state.

Fire this time

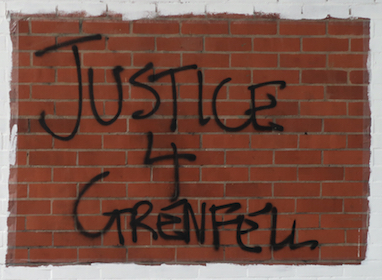

These walls bear witness. ‘Justice’, ‘pity the poor’, ‘fuck the local authority’s Tenants Management Organisation’s, gentrification serving, class-cleansing deception’, they shout. And poignantly, still faintly echoing down the years, from half a century ago, they say, disturbingly, ‘Keep Britain White’.

It’s June 2017, and from the corner of Blechynden Street and Bramley Road, London W10, in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea (RBKC) spectating hundreds and thousands in procession, take in the awesome and awful sight of the burnt out, inner-city housing estate tower, Grenfell. This is North Kensington, aka Ladbroke Grove, aka Notting Hill, land of London’s famous Caribbean-defined Carnival, home to some of the richest plots in the world, historic site of criminal neglect of the poor, overseered by local and national state functionaries − from ghetto of the working-class poor in the 1950s, to ghetto of the super rich in the present day.

The exploitative and racketeering landlords of the 1950s (Rachman the most notorious of them) have been displaced and replaced by early twenty-first century ‘non-governmental organisation’ (NGO) landlords, contracted by the state. In the 1950s the insult and injury visited on new migrant-settler workers from Britain’s Caribbean colonies by racketeering landlords was part and parcel of broader racist attacks on Black working people − where poor White working- class residents of Blechynden and other streets were stirred and directed to attack their new Black neighbours − by, amongst others, Oswald Mosley and Colin Jordan. Today, institutionalised discrimination and xeno-racist brutalisation of the newest non-White migrant-settler working people are routinely administered by state functionaries, and include the provision of sub-standard and deathly public housing estates.

It’s the fire this time that exposes the underbelly of the metropolis, showing the savage menace under which the complaining poor have lived for decades − the sub-standard health and safety traps inhabited by the new poor, the servants and servicers of the nouveau riche, cheek by jowl with their callous wealthy better-offs.

From Tuesday 13 through to Thursday 15 June 2017 a huge fire turned the 24-storey Grenfell Tower block into an inferno that displaced and killed hundreds of residents – to date, over eighty dead or missing, officially; up to 200 missing say families and residents. The fire started on a lower floor and raced up and through the building. The record shows that building safety experts and inspectors warned, in 2014, that the insulation used in Grenfell Tower, and which fuelled the June 2017 fatal fire, had to be used with non-combustible cladding. But on Grenfell Tower combustible polyethylene-filled panels were installed on top of synthetic insulation (Cellotex RS500) made from polyiso-cyanurate, which burns when exposed to heat and gives off cyanide fumes. Yet, the RBKC’s building control team certified that the building work on Grenfell ‘complied with the relevant provisions’. And council building inspectors had visited the site on sixteen occasions between 2014 and 2016.

There is already accumulating evidence of thoughtless and corrupt official practice, along with wilful dismissal and neglect of serious concern voiced by Grenfell residents and neighbours over many years. Indeed, from these people who were reduced to depending on community self-help as the first reliable level of support in the wake of the devastating fire, there is more than a suggestion that this Grenfell killer fire may well constitute a race and class ‘hate crime’ committed by the wealthy and powerful against the relatively poor and marginalised.

Gentrification and a culture of contempt

The Grenfell Tower disaster occurred, arguably, because redevelopment policies allowed for kindling, fuel and toxic materials to be wrapped around the homes of working-class people. The combustible cladding scandal has taken on national proportions, but the crime of Grenfell must be accounted for locally, both in the telling of the story of how this happened, and in the pursuit of justice. And after all the criminality will have been laid out, and the people taken stock of the totality of what is to be done in response to the failures of the state, a wholly new politics appears to be called for− a politics infused with the traditions of the area’s radical past. RBKC’s decisions − from the cladding and insulation work, to a brand new school being built upon the block’s car park − should indict those in positions of authority. Evidently, they thought it expedient to gamble with lives, despite having the deepest pockets of any local authority in the country. Needless austerity and rule by accountants contributed to making Grenfell Tower into a death trap where a fire could rage unabated − making it hotter than a crematorium furnace.

How do individuals and families immediately affected recover? How does local community recover itself? Back in the last century the turnaround after the racist insult and embarrassment of the 1950s saw the then North Kensington local Black-and-White community achieve a degree of everyday non-racist conviviality − ironically, in the longer-term, making North Kensington/the Grove/Notting Hill a choice des-res locality for, first, the hip, and later, the moneyed middle classes and, now, the new gentry. How, today, does this neighbourhood and its wider community come back?

To ask residents in the borough about the Kensington and Chelsea Tenants Management Organisation’s (KCTMO) track record is to receive reports of a litany of examples of dismissal with contempt. Cease and desist orders were sent to those uppity enough to call out the council and KCTMO on their class warfare. These same people who were told to shut up either had their homes destroyed, or were killed in them. This is part and parcel of a bigger story of social and political abuse. A detailed reading of the residents’ GAG (Grenfell Action Group) blog reveals that it is no coincidence that the blaze took so many lives from the poorest part of the richest borough. A Freedom of Information (FoI) request revealed that in 2010 the RBKC’s radical redevelopment plan would have bulldozed the entirety of the Lancaster West estate. GAG contends that it was only the economic crisis that derailed the plans. ‘When and if the housing market eventually recovers we fully expect them to revert to type and come after the rest of Lancaster West’, the blog states. With its redevelopment hampered, the local authority treated Grenfell Tower as an eyesore. Developers turned to the device of prettification by cladding. As one local known as Rhymes put it, ‘They tried to get rid of Grenfell Tower, the community resisted, so they covered it in flammable materials instead’. Gentrification kills, as the pyre of Grenfell testifies.

Long before the fire, Grenfell was recognised as a site of people’s resistance in North Kensington. GAG formed part of a cluster of local resistance networks and social movements that challenged the asset stripping of the area. Community provisions were being put on the auction blocks of a fire sale. The communities that make up North Kensington campaigned to defend their colleges, libraries, nurseries, community centres and open spaces. The alliance of council, big developers and non-state functionaries − like the KCTMO and Westway Trust – which planned to target spaces, denounced the campaigners. The Westway Trust’s plans to redevelop the spaces under and adjacent to the A40 fly-over were publicly challenged, and the Trust’s CEO Angela McConville called off one public meeting with the Westway23 campaign group on grounds of looking after the well being of staff, in effect labelling the campaigners as violent.

Communities against embedded injustice

It is within and against this culture of contempt that Grenfell stands, and where resistance and autonomy have taken root. With the onset of the assault on the Grenfell poor came the resurgence of calls for community self-organisation and collectivism. Immediately disaster struck in North Kensington, a volunteer-led relief and support system was up – even as the state’s working processes stalled. And the voluntary relief effort has fuelled a demand for change, to the effect that for those who operate around a duty of care, care should be a statutory requirement. Direct democracy is becoming a demand. Those bogged down in the logistics of sorting emergency aid and care packages are conscious of working towards something not unrelated to the call for ‘a republic’ (which first emerged decades ago in ‘Frestonia’, just around the corner from Grenfell). This idea, now re-surfaced, underlines the fact that where the state has failed, true community-care has stepped in. North Kensingtonians now know that the conditions under which life flourishes are not provided by the state and its functionaries. There has been a ‘rupturing of the status quo’, as the French-Algerian philosopher Alain Badiou might put it. The violence of the state has been revealed and temporarily removed, and, therefore, truths have been exposed.

Grenfell can be read as a manifestation of the injustices of the present, and it has seen an acceleration in collective consciousness. The summer’s bright sun has shone a light on shadowy figures like the KCTMO’s CEO Robert Black, and senior councillors like Nicholas Paget-Brown and Rock Feilding-Mellen – leaders in the former state of affairs, now resigned.

Events like Grenfell expose any number of embedded everyday injustices. Racist nativism underscored the suppression of numbers in the immediate aftermath of the fire, and overlooked the fact that the majority of those killed were Muslims from North African migrant backgrounds. The state failed to acknowledge the existence of the undocumented. Brexit Britain, in Prime Minister Theresa May’s own words, is a very ‘hostile environment’, where there can be no accommodation of the undocumented. Official non-statutory services, such as the Red Cross, failed to provide safe spaces for the desperate and traumatised for several weeks after the event. Making spaces available and addressing other lapses took persistent lobbying of the authorities.

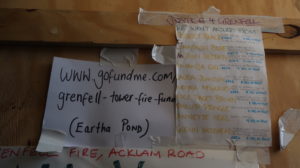

In nativist Britain, you can be burnt to death in the place where you live and then deleted from history. In the immediate aftermath of the fire, those who survived, but could not speak English, were not provided for. Communiqués and signage bore the hallmarks of the Notting Dale of old. If you cannot read English, you do not belong. The people had a different approach. A direct relationship of service to the people, from the people emerged after the fire; translators were sourced, resources were disseminated, aid was delivered to hotels. The tendency of the state is to exclude, whereas the communities of North Kensington operate on the principle that if you are here, you are from here. Thousands went to work to serve the various communities and peoples that make up the area, where discussion of proof of the right to remain was seen as an act of violence. To ask someone who had survived a fire to provide papers was seen as an obscenity to which the community refused to stoop.

And even after the public relations exercise had fallen apart and the state was shown to have utterly failed, its functionaries continued with the hubris of being in charge. To date, the best the government has offered is temporary accommodation and a year’s amnesty for those paperless, traumatised and homeless, which amounts to little more than a stay of execution. Executive powers proposed an emergency local state administration after RBKC’s unmitigated failure. Promised are a government review, a public inquiry, and a criminal investigation of Grenfell.

Reclamation

The people of North Kensington counted their dead and served the living after the fire. Shelter, food, and clothing had to be found. Legal representation, in the face of authorities that would slide away from their responsibilities to devastated and displaced residents, had to be organised. Sensitive trauma support was of necessity on offer, religious as well as temporal. To many survivors, the volunteer systems across the various centres (still operating autonomously from the council and the combined boroughs’ emergency apparatus of ‘Gold Command’) were and are a life-line. Across the area, public-space land is being reclaimed. Maxilla Walk, on the verge of huge and controversial redevelopment, is effectively an occupied public arts space. The Henry Dickens Community Centre, a stone’s throw from the burnt out Grenfell Tower, is now an art therapy centre. Bay 56 under the A40 Westway, where Acklam Road meets Portobello Road, is now known around the Grove as ‘the Village’ and is a central hub in the community’s self-help and aid effort, offering healing activities and care packages. Thousands are engaged in an entirely autonomous aid effort. The state withdrew and went missing in the immediate aftermath of Grenfell. It is not clear how it can come back, and on what terms.

The links between North Kensington past and present are acutely observed – and the product of deep local knowledge.

For Rachman then, read TMO today. For the community’s heroic response in the aftermath of Grenfell, see its phoenix-like re-emergence following the racist violence in the late 50s. And for the treatment of migrants then, see their continued marginalisation today. Excellent piece.

The only thing I would add, is that RBKC and the TMO is typical of the self serving government that has been in power for the past 7 years. The whole system of government is corrupt and is in need of major reform.

Excellent analysis! I had not noticed the ‘We’re all in this together’ written by hand on one of the walls on which the local community expressed their tributes! The very recent disclosure that the local authority will re-house the survivors in alternative accommodation and charge the same rent as the tenant had paid formerly in Grenfell even if the new dwelling is larger serves to illustrate the contempt with which all the victims have been treated! Why was the same reasoning not employed with regard to the cost of ensuring the absolute safety of the materials employed in the refurbishment of the tower block? The echo of James Baldwin’s ‘The Fire Next Time’ is apt!