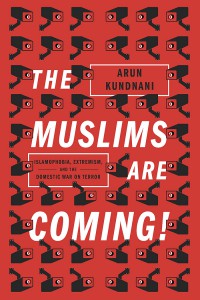

Below is an edited transcript of a talk given by Arun Kundnani, author of ‘The Muslims are coming: Islamophobia, extremism and the domestic war on terror’, in January 2015, shortly after the Paris killings.

The situation we find ourselves in is not entirely new. Most of what we’ve seen over the last few days is familiar from the Rushdie affair, from the moment after 9/11, the moment after 7/7, the moment after the Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons in 2006. Now with the attack on Charlie Hebdo, we see narratives emerging that, in their essentials, are exactly the same: the clash of values, the idea that on ‘their side’ is extremism and violence and on ‘our side’ is liberalism and modernity. So, once again, we are trying to find a place to stand between these two camps of militarised identity politics and the question for us, as anti-racists, anti-imperialists and anti-capitalists, is how, in this context, do we talk about racism, imperialism, capitalism, feminism, religion and freedom of expression? Although we’ve been through these moments since the 1990s, we still struggle to work out how to talk about these things and to define a space where we on the Left can articulate our values and our narratives. Certainly we can’t do that under the slogan of ‘Je suis Charlie’, which is the latest version of this narrative of liberal values. It’s of course easy to show the contradictions of that, beginning with Charlie Hebdo’s exploiting of racial stereotypes in its cartoons.  The claim of being an equal opportunities offender is incorrect: we are familiar with the fact that someone lost their job for anti-Semitism, rightly so, but it wasn’t possible to lose your job for Islamophobia at Charlie Hebdo. And the double standards in the events in Paris are obvious: a demonstration for freedom of expression with Netanyahu as a figurehead is of course ridiculous, given Israel’s killing of journalists in Gaza. It is also ridiculous to talk about freedom of expression in France without also talking about why France has banned protests in relation to Gaza.

The claim of being an equal opportunities offender is incorrect: we are familiar with the fact that someone lost their job for anti-Semitism, rightly so, but it wasn’t possible to lose your job for Islamophobia at Charlie Hebdo. And the double standards in the events in Paris are obvious: a demonstration for freedom of expression with Netanyahu as a figurehead is of course ridiculous, given Israel’s killing of journalists in Gaza. It is also ridiculous to talk about freedom of expression in France without also talking about why France has banned protests in relation to Gaza.

I think we also need to think a bit more carefully about the hidden ways in which we create norms as to what is and is not sayable. We’re not just talking about the obvious forms of censorship, the obvious legislation and the arrests but the much more low-key, everyday, informal censorship that determines what can be heard and what is visible, we need to go with the question of freedom of expression. I was recently involved in producing a report that tried to think critically about UK counter-terrorism policy, which we launched the day before the attacks took place in Paris. The timing was a gift to journalists who wanted to discredit the report. As soon as those attacks occurred, it was much harder to critically analyse the way our counter-terrorist policy is going. Andrew Gilligan of the Telegraph was able to use the launch of the report to say dissent of this kind was just another form of extremism and therefore a precursor to terrorism – no need, then, to examine what is actually being discussed. The space for radical politics closes so that dissent is automatically extremism and on a continuum with terrorism. We need to talk about what a genuine movement for freedom of expression would look like, which is more than just saying freedom of expression is always a double standard. We need an alternative way of thinking about freedom of expression that considers in a more rounded way what is unsayable, what is invisible. Words like extremism, radicalisation and terrorism shape the limits of discourse through their implicit narratives and assumptions. For example, the experience of a population living under the permanent terror of drones cannot be described as an experience of terrorism. If someone wants to say that, they are likely to be charged with being an extremist – even more so if they are Muslim. More broadly, by taking on issues of imperialism and racism we can explain the violence that we saw in Paris, which is ultimately a social and political problem not a religious problem. It’s only an anti-imperialist Left that can provide an alternative to both al-Qaida’s violence and state terrorism.

Official accounts of terrorism

Focusing more specifically on the current counter-terrorism Bill, we should note that this is a continuation of a process, since the late 1990s, of a constant stream of legislation granting new powers to the government in the name of countering terrorism. At the heart of the consensus between the two main parties is a flawed analysis of what causes terrorism, which again we have seen in the debate about the bill. Over the last decade we’ve repeatedly been told by government ministers and by so-called terrorism experts a story about why terrorism occurs and it’s this story that underpins policy. It’s this story that constantly comes from ministers, whether it’s David Cameron or, going back, Hazel Blears or even someone like Jacqui Smith – it doesn’t really make much difference. The speeches they give are essentially the same in this area.

The narrative essentially says that terrorism is caused by the presence of extremist ideology and extremism is defined as opposition to British values – the bulk of attention is on extremism associated with Muslim populations and in these cases the government defines the extremist ideology as a minority version of Islam usually named as Islamism or Salafism, which is seen as somehow being capable of capturing the minds of Muslims and turning them into terrorists. If you accept this perspective, then the challenge is to understand the process by which this extremist, religious ideology takes hold of Muslim minds: this is what people mean by ‘radicalisation’. For some ‘radicalisation analysts’ the role of religious extremist ideology in this process is akin to a conveyor belt that mechanically pushes individuals into terrorism; once someone has adopted the extremist ideology, terrorism is likely to follow sooner or later. For other analysts this process is more complex and depends not only on an ideology but also on psychological factors such as the experience of a recent traumatic event. But whatever nuances are added to the picture, the underlying assumption in all these so-called radicalisation models is the same: that some form of religious ideology is the key element in turning a person into a terrorist.

Now, of course, if you accept that, what you are going to want to do is prevent the circulation of this extremist ideology that plays this role of turning someone into a terrorist. So we’ve seen a wide range of domestic policies which all try to achieve that:

The surveillance of the political and religious lives of Muslims in order to identify what are seen as indicators of radicalisation. For example, through ‘schedule 7’ stops at ports, the police can go through someone’s electronic devices to see if they display these indicators; and there’s a legal requirement to answer any questions.

The surveillance of the political and religious lives of Muslims in order to identify what are seen as indicators of radicalisation. For example, through ‘schedule 7’ stops at ports, the police can go through someone’s electronic devices to see if they display these indicators; and there’s a legal requirement to answer any questions.- Requiring teachers and youth workers who work with Muslims to share information with police anti-terrorism units about those young people and perceived risks.

- Powers under the Terrorism Act 2006, which defines the crime of glorification of terrorism, criminalising individuals for expressing opinions seen as extremist.

- The exclusion and removal of foreign nationals who are thought to have extremist opinions.

- Stripping the citizenship of British citizens believed to be engaged in terrorism or denying them re-entry to the UK.

- Funding specific Muslim leaders to promote an ideological message against extremism on behalf of the government.

- Requiring suspected extremist individuals to undergo de-radicalisation programmes.

- Requiring websites to remove online content thought to be extremist

- Financial restrictions on individuals and charities believed to be engaged in support for terrorism.

- Public pressure on Muslims to declare their allegiance to so-called British values.

It’s worth considering briefly the state of the academic discussion about whether this is a credible account of what causes terrorism. Around 2005–2007, there was a flurry of studies coming from university departments, law enforcement agencies and think tanks, which had all received large sums of money from the US and UK governments, trying to find evidence that some set of religious extremist ideas is the cause of terrorism. This was a field that a lot of academics rushed into because all of this money had been thrown at terrorism studies. To cut a long story short, they went searching for this evidence and either didn’t find it or pretended to find it when really they hadn’t. Gradually, over the last few years, we’ve seen a shift. People who were part of that game are starting to be a bit more honest about the data and starting to acknowledge that this thing does not stand up to scrutiny. Someone like Marc Sageman for example, a former CIA analyst who became an academic and counter-terrorism expert. Ten years ago, he was talking about religious ideology as the root cause of terrorism. Now he has rejected that perspective completely and has a very different way of talking about terrorism. You can find people like John Horgan and Jamie Bartlett, who are in the same place. The new view coming out of academia is that having a belief in extremist Islam, however you want to define that, does not correlate empirically with involvement in terrorism. There may be very good reasons for objecting to reactionary religious beliefs but the idea that they cause terrorism isn’t one.

It’s worth noting that the officially-sanctioned analysis of terrorism has been central to British policy-making is driven by think tanks, in particular Policy Exchange and Quilliam Foundation, which channelled neoconservative thinking from the US into the mainstream of British policy-making. It’s not been an evidence-based process by any means. And obviously it’s convenient for a government that’s facing a critique of its foreign policy to be able to say the blame for terrorism is nothing to do with our foreign policy but it’s to do with this alien extremist ideology that somehow landed in Britain from the Middle East.

Alternative analysis of terrorism

So what then is a better way of analysing terrorism? One thing we might do is look at some of the work done before 9/11, which tends to be more objective. Someone like Martha Crenshaw, for example, who is a scholar of terrorism who was writing in the 1980s, talked about the causes of terrorism in a multi-level way: the level of the individual, the level of the social movement that someone belongs to and the wider social and political context. What we’ve done, since 9/11 especially, is just focus on the level of the individual and think it’s all about that individual’s ideological indoctrination and not think about the wider social and political context and not think about the strategic decision-making within a social movement as to when to use violence and why.

If you look at Home Office figures, for example, of the number of people who’ve been convicted of terrorism-related crimes in Britain, that number more than doubles between 2003 and 2006. Between 2006 and 2009, it then falls back down to the level it was at before 2003. It would be overly reductionist to think that this was entirely due to Britain’s involvement in the Iraq war from 2003 but that’s a large part of what’s going on here. The decision to take part in the Iraq war created a political context in which a small number of radicals decided that violence against their fellow citizens was now legitimate. It’s not that they changed their religious ideology, which is what you would expect according to the official accounts. So in this upsurge of violence from 2003, much more relevant than Islamist ideology, is the news from Iraq of the deaths of hundreds of thousands of civilians, the photographs from Abu Ghraib and the other images of violence in Iraq. In this light, the recent threats of terrorism inspired by al-Qaida are not exceptional but part of a longer historical pattern. What that longer history of terrorism teaches us is that its roots lie in the way that oppositional movements turn to violence in the face of state violence and through their interpretation of that state violence. Think about the anarchists of the late nineteenth century: it was the violent suppression of the Paris Commune in 1871, in which tens of thousands of civilians were killed, which then triggers for a small number of people in that movement the turn to dynamite and assassination across Europe. For the Provisional IRA, it’s the British Army’s violent suppression of the nationalist civil rights movement in Northern Ireland. I think for the 7/7 bombers, it’s the images of mass slaughter in Iraq. Such examples are coming from different movements and histories but they have in common the relationship between state violence and the violence of non-state actors.

I think we can tell a similar story about the so-called Islamic state: how it emerged from the conflict in Iraq, in particular the incarceration of hundreds of thousands of Iraqis in Camp Bucca. We didn’t notice that history unfolding from 2009 because it was happening at a time when we’d lost interest in Iraq. We wanted to stop talking about Iraq. Chelsea Manning was at least, by leaking material, trying to raise our awareness about what was happening in Iraq –– for this, she was put before a military tribunal and subjected to solitary confinement in the United States. Now, we’re bombing Iraq for a fourth time since the end of the Cold War and repeating again that same cycle of violence.

Consequences of counter-terrorism policies

Turning more specifically to the consequences of domestic counter-terrorism policies, I think obviously the main policy here in terms of radicalisation and extremism is the Prevent policy. Its flaws have been well rehearsed so I’ll go through them fairly quickly. The first issue is the way in which it sets up a selective understanding of what extremism is. You will remember that, when the policy was introduced, the funding for Prevent was allocated in proportion to the Muslim population in each local authority area in England and Wales (based on the 2001 census, the first one to ask a question on religion). The government literature talked about the number of Muslims in a particular area being a proxy for the risk of radicalisation. And, of course, the far Right falls out of the picture here –it’s incredibly marginal. If you read how, for example, the English Defence League is talked about in government policy discourse, it is never seen as a terrorist organisation, even though its members are involved in threats, incitement, and acts of violence, which they carried out in a systematic fashion after the murder of Lee Rigby two years ago. By any objective definition, that counts as a terrorist organisation. Yet there are people like Douglas Murray, a neoconservative who advises on counter-terrorism policy, who has publicly said that the English Defence League is in some respects what he would like to see as a grassroots response to Islamist extremism.[1] When you look at the number of people who have died in incidents of terrorism in Europe between 1990 and 2010, the number who have been killed by far-right activists is roughly the same as those who have killed by jihadist attacks – so the two are more or less of the same order if you want to use that as a measure. The way we think about security threats is obviously socially and politically constructed; it is not derived from an objective assessment of the kinds of violence that exist in our society.

The second point about Prevent is the way in which it draws professionals from a range of different sectors into becoming the eyes and ears of the counter-terrorism system. Whether you are talking about obligations on schools to share information with the police, obligations on universities to share information, youth workers, doctors – it’s a way in which non-policing public sector workers have been sucked into becoming part of the counter-terrorism system. This is backed up with tens of thousands of public sector workers being trained in so-called radicalisation awareness, which essentially is inculcating these professionals with the official, flawed, racialised analysis of radicalisation. This is one of the ways in which the thinking that is bound up with this official narrative is brought down into our everyday life and creates a set of prejudices about what kinds of behaviour and talk is acceptable. Any form of radical politics then finds less and less space, and a culture of self-censorship is fostered because to talk about foreign policy, for example, can now attract the suspicion that you might be labelled an extremist if you are in a school, in a youth club or in a university student society.

There is a new category of speech, which is not unlawful in a criminal sense but is politically unacceptable –it’s extremist speech, that which cannot be said, the experiences that cannot be conveyed, the knowledge that cannot be shared. Extremism here is a vague term: it’s never precisely defined. Obviously, it’s meaningless to define extremism as the opposite of British values. Historically, the label of extremist has been attached to all kinds of people: Martin Luther King was repeatedly accused of extremism during the sixties. In the present day, people like Tariq Ramadan and Salma Yaqoob are called extremists.

The final point here is the Channel project, which is the part of Prevent that looks at individuals who’ve been identified by the police or intelligence services as at risk of radicalisation and then tries to develop interventions to de-radicalise them. By definition, this is not about criminal activity; Channel operates in what in the jargon is called ‘the pre-criminal space’. If there’s suspicion of criminal activity, then the response is meant to be a police criminal investigation, not Channel. So it is law-abiding people who just happen to, for example, express radical opinions. This is somewhat shrouded in secrecy but Rizwaan Sabir of Edge Hill University has given us an actual account of a teenager, Jameel Scott, who has been through Channel and been able to speak about what that was like.[2] Scott was involved in a protest at Manchester University against the Israeli Deputy Ambassador. He was not guilty of any crime but was referred to Channel because of his political activism and his background. The police then came to his extended family and to his teachers and engaged in a process of attempted de-radicalisation; they regularly sat down with him and tried to say that he needed to disassociate himself from people in his social group, who were perceived to be extremists – actually, they were members of the Socialist Workers Party. See the slippage here –from talking about Islamist extremism to Trotskyism.

What the new legislation is doing is actually putting all of this on a statutory footing so it will be a legal requirement for schools, for universities, for doctors to participate in these counter-radicalisation and de-radicalisation programmes. We used to have in the development of local authority policy a ‘duty to involve’: if you wanted to introduce a policy like Prevent in a certain area you had a duty to involve the local community in shaping the priorities locally of how that policy would be implemented. Now, we just have the duty coming from central government that you will impose this, whether you are a university, whether you are a local authority, whether you are a nursery school. We have seen guidance coming out for nurseries on implementing Prevent; we’re talking about 4-year-olds and how they may be perceived as at risk of radicalisation,[3] and guidance has also been issued for optometrists.[4]

The ‘generational struggle’

In universities, from the 1980s there has been a statutory duty to defend freedom of speech but now the new guidance, backed by the statutory duty in the new Counter-Terrorism and Security Bill, creates a situation where a person who wants to speak at an event on a university campus has to be approved by the counter-terrorism unit of the local police department. That, in effect, is what the new guidance is saying and it’s giving the police a kind of informal censorship power. The guidance says universities must take seriously their duty to exclude those expressing extremist views. How are they going to implement that? By having a Prevent officer on the campus to scrutinise who is speaking and what are the activities of groups that are considered radical or extremist. That Prevent co-ordinator will then liaise with the police counter-terrorism unit, who will have a list of people who cannot speak. So using the language of risk assessment and of tackling extremism, we have created this kind of censorship power on campuses and we’ve created this normalisation of surveillance on campus, all of which is an odd way to teach the ‘British value’ of freedom of expression. Of course, these same structures will spill over to other forms of political activism: we saw this already with the upsurge in student protests around cuts to education a few years ago. It was the Prevent officers on universities who were trying to provide police forces with advance information about protests and demonstrations, those involved and so forth.

That, in effect, is what the new guidance is saying and it’s giving the police a kind of informal censorship power. The guidance says universities must take seriously their duty to exclude those expressing extremist views. How are they going to implement that? By having a Prevent officer on the campus to scrutinise who is speaking and what are the activities of groups that are considered radical or extremist. That Prevent co-ordinator will then liaise with the police counter-terrorism unit, who will have a list of people who cannot speak. So using the language of risk assessment and of tackling extremism, we have created this kind of censorship power on campuses and we’ve created this normalisation of surveillance on campus, all of which is an odd way to teach the ‘British value’ of freedom of expression. Of course, these same structures will spill over to other forms of political activism: we saw this already with the upsurge in student protests around cuts to education a few years ago. It was the Prevent officers on universities who were trying to provide police forces with advance information about protests and demonstrations, those involved and so forth.

At the harder end of this has been the step up, over the last few years, of individuals being prosecuted for simply expressing opinions or possessing literature. The most interesting case here is one that Victoria Brittain has written about: Ahmed Faraz. He was in prison for a year before he was able to win an appeal. The charge against him was essentially owning a copy of Sayyid Qutb’s Milestones, which is not a terrorist manual but a work of religio-political analysis. So we have a situation in twenty-first century Britain where someone spent a year in prison for owning a book, not of course a cause that anyone’s taken up in the recent focus on freedom of expression.

Then, we’ve seen the way in which this notion of British values has been wrapped up in this whole process, the notion that there is some set of values that is missing in a particular community and that that might be part of the solution – which, of course, has no real basis but becomes a way of constructing again this kind of militarised identity politics – of them and us – of which we’ve seen so much of over the past few days. To tell young people who already feel British, but on their own terms, that they need to somehow undergo a change of their basic values to adjust to this society, is incredibly alienating and undemocratic.

This policy and the discourse around it leads to what Cameron calls a ‘generational struggle’ – the idea that we’re not simply dealing with a set of individuals who are engaged in criminal activity but that there is a much deeper cultural problem in a whole community, which is a disastrous way to counter the terrorist’s narrative that there is a war of the West against Islam. What we need instead is to drop this focus on religious ideology and focus much more precisely on the notion of the violence itself. I think we need a movement that’s going to be able to handle this kind of two-sided approach to this problem so that we are able to condemn the violence that we saw in Paris recently at the same time as condemning state violence that is in an ongoing interaction with it. If we are going to be able to break that cycle and offer an alternative, I think we need to think about that interaction between state violence and non-state violence and the way in which they mimic and reinforce each other. For me, one of the most profound thinkers on these questions of violence was Martin Luther King who, when he was speaking in 1967 in New York, said: ‘As I have walked among the desperate, rejected, and angry young men, I have told them that Molotov cocktails and rifles would not solve their problems. I have tried to offer them my deepest compassion while maintaining my conviction that social change comes most meaningfully through nonviolent action. But they asked, and rightly so, “What about Vietnam?” [Today, we could substitute Iraq, Afghanistan or Palestine.] They asked if our own nation wasn’t using massive doses of violence to solve its problems, to bring about the changes it wanted. Their questions hit home, and I knew that I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today: my own government.’[5]

This policy and the discourse around it leads to what Cameron calls a ‘generational struggle’ – the idea that we’re not simply dealing with a set of individuals who are engaged in criminal activity but that there is a much deeper cultural problem in a whole community, which is a disastrous way to counter the terrorist’s narrative that there is a war of the West against Islam. What we need instead is to drop this focus on religious ideology and focus much more precisely on the notion of the violence itself. I think we need a movement that’s going to be able to handle this kind of two-sided approach to this problem so that we are able to condemn the violence that we saw in Paris recently at the same time as condemning state violence that is in an ongoing interaction with it. If we are going to be able to break that cycle and offer an alternative, I think we need to think about that interaction between state violence and non-state violence and the way in which they mimic and reinforce each other. For me, one of the most profound thinkers on these questions of violence was Martin Luther King who, when he was speaking in 1967 in New York, said: ‘As I have walked among the desperate, rejected, and angry young men, I have told them that Molotov cocktails and rifles would not solve their problems. I have tried to offer them my deepest compassion while maintaining my conviction that social change comes most meaningfully through nonviolent action. But they asked, and rightly so, “What about Vietnam?” [Today, we could substitute Iraq, Afghanistan or Palestine.] They asked if our own nation wasn’t using massive doses of violence to solve its problems, to bring about the changes it wanted. Their questions hit home, and I knew that I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today: my own government.’[5]

I think that gives us an important starting point precisely because it takes us into that relationship between state violence and non-state violence. And King goes on to talk about how we need to begin by tackling the giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism and militarism, which he says are woven into societies which place ‘profit motives and property rights’ above human beings. His words are as relevant today as ever.

Related links

IRR News story: ‘The Great British Values Disaster – education, security and vitriolic hate‘

IRR report: Spooked! How not to prevent violent extremism

IRR News story: Where monoculturalism leads

IRR News story: ‘Apologists for terrorism’: dissent and the limits of free expression

Claystone report: A Decade Lost: Rethinking radicalisation and extremism

Read about The Muslims are Coming by Arun Kundnani here

Thanks for this thoughtful and thought-provoking piece. As an education professional I am often asked about FBV by school,. Indeed I’m presenting on FBV at an Osiris conference in March. I’ve been looking for the counterbalance argument and this, with the piece by Bill and Robin, gives me something sensible to say.

its all nice though when you have people that truly believes killing you for criticizing them is justified by their religion and incites them to do it while they themselves believe they will be rewarded for it then the argument falls short we simply cannot divorce islam from islamists. And not just islamists, when certain muslim countries populations have as values to put people in jail for criticizing their religion, and majorities that believe death is the right penalty for apostasy then what we need to look at is the definition of fanaticism and extremism.

politicians tend to dance around the idea trying to say its a difference between islam and jihadists that only 1% of muslims are extremists.. well it depends how e define it…

stoning women for adultery is favored by 89% in Pakistanis, 85% in Afghanistan, 81% in Egypt, 67% in Jordan, ~50% in ‘moderate’ Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand, 58% in Iraq, 44% in Tunisia, 29% in Turkey, and 26% in Russia.

84% of Egyptian Muslims,86% of Jordanian Muslims,30% of Indonesian,76% of Pakistanis 51% of Nigerian support the death penalty for leaving islam

id say stoning someone to death and killing someone who leaves your club all of which demanded by your religion is fanatic and extremism.

Politicians need to stop being worried with offending muslims when it comes to womens rights, gay rights, freedom of speech. Because we certainly condemn nationalists when they say idiot shit about females, muslims,gays etc. Why then must our criticism to intolerance die at the doors of islam when most islamic countries have horrible record on human rights abuse? and the quran itself dictates women to be half as worth, and unbelievers worth bellow slaves. We did not tolerate south african apartheid, why then do we tolerate when muslims see themselves as tolerant for believing christians and jews should pay taxes within their society to live peacefully? because that is apartheid!

ofc there are different levels of belief and different schools, those who practise those who dont etc but that goes without saying.

islam needs to reform, and its nearly impossible for muslims themselves to raise their voices for change without being persecuted. The biggest flaw is western politicians dont go far enough and tip toe around someones religious feelings, feelings which leads people to justify murder.

another problem is muslims confuse criticism with persecution.

and yes our societies have become more unequal and more orwelian which lead to more populism and more hate which we rightfully condemn.So muslims shouldnt ask for special treatment when they are subject to the same scrutiny as everyone else

According to Dr Kundadni, “having a belief in extremist Islam … does not correlate empirically with involvement in terrorism.”

That’s news to me.

My questions to Dr Kundadni:

What is the name of the person who did the statistical work and then concluded that there was no empirical correlation?

Where was the finding published about this lack of empirical correlation?

Can you give us a link to the URL of the scholarly paper you cite?

Pape, Dying to Win: The Strategic Logic of Suicide Terrorism. London: Gibson Square 2006

Why people still make use of to read news papers when in this technological world all is existing

on net?