A tribute to Buzz Johnson (1951–2014), who created in the UK one of the most important and prolific black publishing houses on and for Caribbean peoples.

I feel that I met Norris ‘Buzz’ Johnson nearly a decade before we actually met, human to human. In 1968, I found my first school teaching post in Scarborough, Tobago. Without knowing it then, I was teaching Buzz’s family, including a remarkable 13-year-old cousin of his, Betty, who wrote some radiant poems in my English classes. She left two with me which seemed to express something elemental about her and Buzz’s beautiful island and which have stayed with me all my subsequent life in teaching. Now I think that it was the spirit of Buzz and Tobago’s proud people who were also speaking in Betty’s words:

At the Break of Day

Early in the morning,

When the first cock crows

And the grey morning fills the East

And the fog rises out of the streams;

Some men sleep on

But, some are already awake

Thoughtful and worried

Of the coming day.

Or

Old Ships

Old ships sail like swans asleep

In the deep waters they dip their bows,

Heading towards the rising sun

And the morning in its dawn.

Buzz’s own dawn began in November 1951 among fishing boats in the village of Buccoo in the south of the island, just onshore from its renowned reef. I had some friends there and was a frequent visitor, staying nights in their beachside house. One dawn, I went out with my friend in the boat of one ‘Mr Johnson’, a warm and powerful man with a Herculean physique, whom Buzz ten years on in London told me was his uncle. As the sun rose over the reef, he pulled up his many pots, heavy with lobsters, and on one pot was a large and formidable octopus which slithered into the boat and began sliding up the hull towards my friend and me, its long tentacles writhing menacingly. Mr Johnson raised his oar and with a single blow he crushed it. ‘That will fix him!’ he exclaimed, and carried on with his pots.

At that time Buzz was studying in southern Trinidad, where he had migrated with his close family, accompanying his father who had taken a job in the oil industry. They lived in Fyzabad, which had been the hub of the rebellion of oil workers in June 1937, when workers of all sectors in Trinidad went on strike for better wages and conditions, and greater opportunities. This insurgency, which included thousands of workers from the smaller islands to the north of Trinidad as well as Trinidadians, had been led by a pioneering Grenadian trade unionist and political militant, Tubal Uriah ‘Buzz’ Butler, who lived in Fyzabad. Labelled by the colonial authorities as a ‘fanatical negro’, he was kept in jail for seven years between 1938 and 1945. Many years later, I began to realise the significance of Norris Johnson’s sobriquet. He and Butler were both arrivants from neighbouring islands and had lived in the same town: two remarkable men called Buzz of two different generations.

At that time Buzz was studying in southern Trinidad, where he had migrated with his close family, accompanying his father who had taken a job in the oil industry. They lived in Fyzabad, which had been the hub of the rebellion of oil workers in June 1937, when workers of all sectors in Trinidad went on strike for better wages and conditions, and greater opportunities. This insurgency, which included thousands of workers from the smaller islands to the north of Trinidad as well as Trinidadians, had been led by a pioneering Grenadian trade unionist and political militant, Tubal Uriah ‘Buzz’ Butler, who lived in Fyzabad. Labelled by the colonial authorities as a ‘fanatical negro’, he was kept in jail for seven years between 1938 and 1945. Many years later, I began to realise the significance of Norris Johnson’s sobriquet. He and Butler were both arrivants from neighbouring islands and had lived in the same town: two remarkable men called Buzz of two different generations.

The teenager Buzz travelled on a daily basis to the town of San Fernando (which housed the headquarters of the Oil Workers’ Trade Union) to attend a government secondary school there. He always expressed pride that he was educated in a state comprehensive school rather than a private or elite school, and fared well there, moving on to college in Point Fortin, a refinery bastion of Trinidad’s largely American-owned oil industry. His school days coincided with the rise of the Black Power movement across Trinidad and Tobago, leading to February 1970, when thousands of Trinidadians and Tobagonians took to the streets and elements of the Army mutinied, in opposition to the mainly white-owned and foreign power interests across the nation. In addition, like many of his contemporaries, he was much affected by events elsewhere: the harsh treatment and expulsions meted out to eastern Caribbean students in their resistance to racism at the Sir George Williams University in Montreal, and the farcical British imperial interference in the tiny island of Anguilla in 1969, when Anguillans broke away from the St. Kitts government, under which they had spent years of authoritarianism and neglect.

So, when he left Trinidad to further his education in London in 1971, he had already understood many of the ways of imperialism and its then-times Caribbean fabric, as well as people’s resistance to it, and he carried that consciousness to Hackney and the working class east of the old Empire’s metropolis. He studied at Middlesex Polytechnic, now Middlesex University and gained a Master’s degree at City of London Polytechnic as well as becoming a student at the London School of Printing. I first met him when we were both involved in the campaign to free the trade union militant and organiser of the unemployed, Desmond Trotter of Dominica, who had been framed on a murder charge and condemned to hang by the neocolonial government of Patrick John, much dominated by the Geest and Cadbury/Schweppes monopolies which owned most of the island’s banana, cocoa and citrus plantations. We worked closely with Liberation (formerly the Movement for Colonial Freedom) and frequently met at its north London office in Caledonian Road. As we talked, we realised some of the unlikely connections of our previous lives. Trotter was eventually reprieved and released, largely through intense international pressure, in April 1976.

By 1982, when I returned from working in teacher education in Grenada, Buzz had founded Karia Press and we found another shared area of interest. I was also deeply involved in progressive publishing initiatives. I had helped establish Fedon Publishers in Grenada – the Revolution’s publishing house, was a member of the Writers’ and Readers’ Publishing Cooperative and had worked to create ‘Young World Books’, a series of internationalist books for young people sponsored by Liberation. So we had much in common, and met frequently to exchange ideas and discuss new projects. At Young World Books we had published Tales of Mozambique[1] (republished by Karia Press in l990), the Angolan young people’s novel by Pepetela, Ngunga’s Adventure,[2] a poetry anthology honouring the life and struggle of the East London teacher Blair Peach, killed by the Metropolitan Police at an anti-fascist demonstration in Southall in April 1979, One for Blair,[3] and an anthology of Grenadian writers, Callaloo.[4] As we discussed our books and the wiles and tentacles of a new imperialism, I remembered Buccoo and Buzz’s uncle and the advancing octopus. Somehow it all seemed to connect.

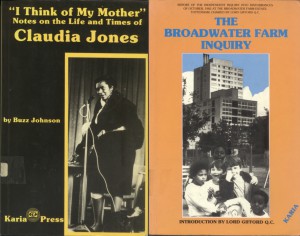

Buzz’s sheer publishing energy, considering his paucity of resources and money, meant that Karia’s books appeared with an astonishing frequency, outstanding books of extraordinary diversity. Caribbean poetry and fiction, history, autobiography, studies of Caribbean languages by the region’s prime linguists – St. Lucian Morgan Dalphinis[5] and the Guyanese scholar of linguistics Hubert Devonish[6] were all set in print for readers in Britain, the Americas and the Caribbean itself, plus works about Caribbean life in Britain – about schools, trade unions, social conditions and protest. There was also Buzz’s own book about his compatriot and hero Claudia Jones, migrant from Trinidad to New York who had been expelled from the US to Britain because she was an ever-active black Communist, organiser of black resistance in Ladbroke Grove and Notting Hill and founder of the Notting Hill Carnival. ‘I Think of My mother’: notes on the life and times of Claudia Jones[7] was a genuinely innovative book which helped to keep Claudia’s message alive and burning at the centre of Caribbean struggle in London.

Among Karia’s other pioneering books was Belizean Amos Forde’s account of the virtually unknown and unrecognised British Honduras forestry workers who spent the second world war felling trees in Scotland, called Telling the Truth.[8] Many Struggles[9] by the Budapest-born scholar Marika Sherwood told of the all-important war-time contribution of West Indian workers and service personnel in Britain. Buzz published a book by another remarkable Tobagonian from the small fishing village of Charlotteville, the scholar J. D. Elder, whose African Survivals in Trinidad and Tobago[10] traced the persistence of Africa in the language, religions, arts and crafts and social organisations of the people of the new nation. There were collections of poetry from Pearl Eintou Springer of Trinidad[11] and Elean Thomas of Jamaica,[12] two revolutionary poets from both ends of the Caribbean (the title of Springer’s book, Out of the Shadows, seemed to emblematise the authors whom Buzz published) and the dynamic rap verses of the rhymester from East Dry River, Port of Spain, Brother Resistance, with the title Rapso Explosion.[13] Karia also published the first complete volumes of two Grenadian authors who came to prominence during the years of the ‘Revo’, and whose work had featured in Callaloo; Jacob Ross’s Song for Simone[14] and Merle Collins’s Because the Dawn Breaks.[15] Both writers have subsequently become recognised as major Caribbean authors. Karia also published Conversations,[16] a collection of essays, speeches and interviews by Barbadian George Lamming, one of the region’s greatest novelists.

Buzz’s achievement with Karia Press and the scope and sheer rapidity of production of its books during a short period (over fifty volumes within a decade) published from a Hackney council flat, cannot be overestimated. This publisher was often near-penniless like his role-model Claudia, yet still managed, through his devotion to his people’s voices finding the printed word, to keep on publishing. I could never fathom how he succeeded in keeping on keeping on with his relentless and apparently unstoppable bookmaking. It defied his impoverished personal circumstances and wherewithal, yet the books kept on coming. He published two long reports on the 1985 Broadwater Farm Estate disturbances in North London, one in 1986[17] and a follow-up in 1989[18] as well as Loosen the Shackles: first report of the Liverpool 8 Inquiry into race relations in Liverpool, also in 1989.[19] He also added to Karia’s history portfolio by publishing Evelyn O’Callaghan’s The Earliest Patriots,[20] a part-fictional narrative of ‘the true adventures of certain survivors of Bussa’s Rebellion’ of 1816 in Barbados, and the autobiographies of Africans in Africa and Britain with Dispossessed Daughter of Africa by Carol Trill,[21] In Troubled Waters by the Sierra Leone-born Ernest Marke[22] and The Autobiography of a Zimbabwean Woman by Sekai Nzenza.[23] His devotion to Africa was also manifest in his publishing of Tell Them of Namibia,[24] poems from the National Liberation struggle waged by SWAPO (South West African People’s Organisation).

Buzz’s achievement with Karia Press and the scope and sheer rapidity of production of its books during a short period (over fifty volumes within a decade) published from a Hackney council flat, cannot be overestimated. This publisher was often near-penniless like his role-model Claudia, yet still managed, through his devotion to his people’s voices finding the printed word, to keep on publishing. I could never fathom how he succeeded in keeping on keeping on with his relentless and apparently unstoppable bookmaking. It defied his impoverished personal circumstances and wherewithal, yet the books kept on coming. He published two long reports on the 1985 Broadwater Farm Estate disturbances in North London, one in 1986[17] and a follow-up in 1989[18] as well as Loosen the Shackles: first report of the Liverpool 8 Inquiry into race relations in Liverpool, also in 1989.[19] He also added to Karia’s history portfolio by publishing Evelyn O’Callaghan’s The Earliest Patriots,[20] a part-fictional narrative of ‘the true adventures of certain survivors of Bussa’s Rebellion’ of 1816 in Barbados, and the autobiographies of Africans in Africa and Britain with Dispossessed Daughter of Africa by Carol Trill,[21] In Troubled Waters by the Sierra Leone-born Ernest Marke[22] and The Autobiography of a Zimbabwean Woman by Sekai Nzenza.[23] His devotion to Africa was also manifest in his publishing of Tell Them of Namibia,[24] poems from the National Liberation struggle waged by SWAPO (South West African People’s Organisation).

Buzz’s commitment to education for equality for Caribbean children in London was expressed in the vibrant We are Our Own Educators![25] by Valentino A. Jones, a Grenadian teacher at the Josina Machel Supplementary School in Hackney (named after the pioneer Frelimo militant of Mozambique). Buzz had a passionate and ever-active belief in the meaning of the book’s title and was a frequent helper in the school’s classes. In his Publisher’s Note to the book, Buzz writes that ‘Karia Press, like the Josina Machel Supplementary School, holds the view that education is a vital instrument in our struggle’, and his earnest words signalled his dedication to the Grenada Revolution’s maxim, ‘Education is a Must!’ In 1991, he republished the original seminal New Beacon Books pamphlet by the imprisoned Grenadian revolutionary Bernard Coard, who had written the epochal How the West Indian Child is Made Educationally Sub-normal in the British School System[26] two decades before. It followed the publication in 1988 of U.S. War on One Woman[27] by a leading woman militant of the Revolution and Coard’s wife Phyllis, and was a prison diary detailing the bogus procedures of the trial of the seventeen imprisoned revolutionaries and the brutality of their captors.

I was deeply proud to find myself on the Karia list in 1989 when Buzz published my memoir of the Grenada Revolution, Grenada Morning,[28] and followed this with my study of Ethiopia’s literacy campaign, A Blindfold Removed,[29] in 1991. By this time I had been working for Sheffield’s Education Department for five years, and Buzz often managed to despatch Karia writers to Sheffield when they stayed in London. Elean Thomas and Merle Collins read their poems in Sheffield schools and at the city’s African-Caribbean centre SADACCA, and the super-dynamic Brother Resistance electrified many a South Yorkshire classroom. In 1989, the mighty Jamaican historian Richard Hart, author of the classic study Slaves who Abolished Slavery, did a northern launch of his account, published by Karia, of the birth of the workers’ and national movements in Jamaica (1936-1939), Rise and Organise,[30] also in SADACCA. On one of his visits to Sheffield, Buzz watched a storytelling session in a primary school by a young dreadlocked Zimbabwean named Chisiya, who was a student of Electronic Systems and Control Engineering at Sheffield Polytechnic. He was strongly impressed and published a collection of his stories for children from Zimbabwe, African Lullaby.[31] It was as if he would find writing worthy of publishing at every juncture, everywhere, at every moment – which he did, removing the alienation and elitism from the practice of publishing, making it the property of ordinary people and giving it a new and precious inclusiveness. I know this well, for as one of Karia’s unofficial publicists, I must have reviewed almost all its books, often in the Morning Star, African Times, Liberation or the Caribbean Times. I couldn’t get enough of Buzz’s printed children.

So where are all these books now? Buzz tried hard, with all his being, to promulgate and disseminate his offspring, but he had little money, few resources and relied much on his friends and political allies to publicise and distribute them. I remember asking him where he kept the thousands of Karia books that he had published in the less than a decade of its most productive life. He told me that he had them stored in a leaky container somewhere in East London. ‘You better get them out of there, sharpish, Buzz’, I said. He nodded philosophically and steupsed: ‘It ent easy man’, he murmured. And it wasn’t. He would take some in his baggage when he visited Tobago to see his mother, but each time that wasn’t much more than handfuls. With few secure and professional distribution networks working with him, it became a huge personal task, which he never saw as burdensome, but undertook with a relentless energy and optimism, and his indefatigable smile.

Buzz’s East London-based Karia Press was one of the major triumvirate of black community publishing initiatives of twentieth-century London, along with Trinidadian John La Rose’s groundbreaking New Beacon Books of North London and Jessica and Eric Huntley’s Ealing-based Bogle-L’Ouverture Publications of West London. Margaret Busby of Allison and Busby worked in a more mainstream publishing market with a base in Noel Street in Soho, but still published a powerful array of reissued works by seminal Caribbean writers like C. L. R. James, George Lamming and Ralph de Boissière, while also publishing new works by contemporary Caribbean writers like Guyana’s Roy Heath. Unlike New Beacon and Bogle L’Ouverture, Karia had no attached bookshop to retail its works. Buzz had only a cramped Hackney council flat and a sea of commitment, taken from his sublime birthplace and brought to the streets of East London.

Buzz’s legacy is his books, all the Karia messages that he held dear and published in the most unpromising of personal circumstances. What is imperative is that these works be nourished and treasured and retained, for they may never be reprinted and they hold an all-but-hidden and ignored history of Caribbean and African lives in three continents, frequently wrestling with the cruelty and deformity of imperialism and racism in their many venues and manifestations. Buzz was in every sense an activist-publisher, in the very hearts of organisations like Caribbean Labour Solidarity, Liberation, the Institute of Race Relations and the Claudia Jones Organisation of Stoke Newington, close to his Hackney home. His neighbours remember how his apartment was always open to them, how those still struggling with English went to him for help and advice, and how, in noble Tobagonian tradition his door was never locked. They recall how he constantly encouraged their young people to work, learn, take responsibility and organise, and never to become defeatist, dispirited or demotivated. In short he was a people’s exemplar as much as he was a people’s publisher, always, as in the words of one of his favourite poets, Peter Blackman, finding and affirming ‘excellence in the ordinary’,[32] and supporting the working class people around him whose lives he shared, those who are, as his cousin Betty described in her Tobago home,

already awake,

Thoughtful and worried

Of the coming day.

For how his publishing activities worked out those words: to find excellence in the most unrecognised and neglected of contexts, and print and spread its message in the midst of hope and struggle. That’s what he achieved, and there are many in London and his Caribbean home who will always be grateful that he crossed their lives, living out the words of that other Buzz of Fyzabad, who declared in December 1937 that:

There is no power, no bribe, to make me turn aside from the paths of truth and beauty and freedom. Beauty and freedom and all that these contain fall not like ripened fruit about our feet. We climb to them through years of sweat and pain; without life’s struggles none do ye attain! We must all struggle and keep struggling until the goals of truth, freedom, beauty and liberty are reached.[33]

A true publisher’s watchwords; Buzz’s watchwords indeed.

Related links

Read an IRR News obituary: Buzz Johnson: 1951 – 2014

“This publisher was often near-penniless like his role-model Claudia, yet still managed, through his devotion to his people’s voices finding the printed word, to keep on publishing.”

A wonderful tribute to an inspiring man, thank you for sharing. We are indeed – Our Own Educators!

I am conducting research into literacy-focussed publishing programs and reading programs and have not been able to find any information related to these types of activities in any of the Caribbean Islands (eg. Jamaica, St Kitts & Nevis, St Lucia, St Vincent & The Grenadines, Trinidad & Tobago).

Any assistance you could provide me regarding this matter would be invaluable to my research project.