Playwright David Edgar takes the long view on conservative philosopher Roger Scruton, recently sacked from a government post – particularly his promotion of ‘unthinkable’ views on race and immigration as editor of Salisbury Review.

I last saw Roger Scruton in the flesh in 2018, at a theatre conference to which he had been invited to represent the conservative persuasion. He clearly enjoyed playing the role of amiable old Tory buffer; he was sitting next to an African-Caribbean playwright to whom he was as polite as she was to him. He didn’t mention the fact that, had advice given in a magazine he edited been taken, she probably wouldn’t have been there at all.

The furore over the New Statesman interview on 10 April 2019 which saw Roger Scruton sacked from a government advisory position has allowed him and his supporters to paint him as an erudite if other-worldly traditionalist who was victim of an unethical journalistic sting. His history reveals the truth to be rather different.

Knighted in 2016, Scruton was dismissed from his unpaid job as chair of the government’s Building Better Building Beautiful Commission on the afternoon of the publication of an interview by New Statesman deputy editor George Eaton. Scruton’s statements concerned George Soros (‘anyone who doesn’t think there is a Soros empire in Hungary has not observed the facts’), the ‘sudden invasion’ of Hungary by ‘huge tribes of Muslims’, the Chinese (‘they’re creating robots out of their own people … each Chinese person is kind of a replica of the next one’) and Islamophobia (‘a propaganda word invented by the Muslim Brotherhood’). On the question of China, Scruton has a case that he was misrepresented: Eaton implied (particularly in a tweet) that the comment was a slur on the Chinese people, while it was clearly an attack on the Chinese government. Following Scruton’s dismissal, Eaton celebrated his scalp by posting a picture of himself swigging champagne (for which he has apologised).

Not surprisingly, this questionable practice (criticised by the New Statesman readers’ editor Peter Wilby, in a thoughtful piece) inspired many Conservatives to leap to Scruton’s defence, particularly neoconservative Douglas Murray, Spectator associate editor and himself no stranger to controversy. Murray wrote two Spectator articles describing Scruton’s sacking as ‘not just a scandal, but a biopsy of a society’ (a ‘character assassination’ which exposed the urgent ‘necessity of free-thought’ over ‘bland, dumb and ill-conceived uniformity’). Again in the Spectator, Scruton defended himself, both against Eaton’s charges, and on other charges raised on Buzzfeed last November, including a quotation on gay rights. As Scruton put it: ‘Apparently I once wrote that homosexuality is “not normal”, but nobody has told me where, or why that is a particularly offensive thing to say.’

Well, I can help there: the remark was made in the Daily Telegraph on 28 January 2007. Last month, Scruton argued that homosexuality wasn’t normal in the sense that red hair isn’t normal, but in 2007 he argued something rather different: that gay people shouldn’t be treated as normal, that ‘it is no more an act of discrimination to exclude gay couples’ from adopting children ‘than it is to exclude incestuous liaisons or communes of promiscuous ‘swingers’’.

The fact that versions of Scruton’s remarks in the New Statesman on Islamophobia and on the ‘Soros empire’ had been published in a different form on Buzzfeed six months before raises the question of why government housing secretary James Brokenshire waited so long to sack him (at the time, he was defending Scruton to the hilt as a ‘champion of free speech and free expression’). But a greater mystery is why George Eaton didn’t ask Scruton about his past.

The Salisbury Review and repatriation

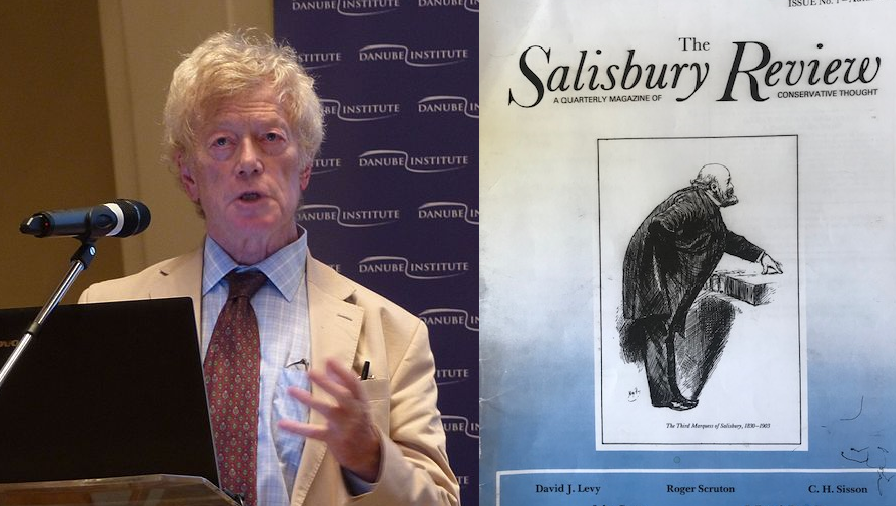

Converted to conservatism by his horror at the May 1968 student uprising in Paris (which he witnessed), Roger Scruton came to public prominence as a member of the Peterhouse school of high-church Conservatives associated with the Cambridge college, many of whom were alarmed by Margaret Thatcher’s commitment to free market economics and the rhetoric of liberty, which they felt downplayed traditionalist Conservative beliefs. So Maurice Cowling’s introduction to the 1978 Conservative Essays (to which Scruton contributed) insisted that ‘the sort of freedom’ that conservatives want is a freedom ‘that will maintain existing inequalities or restore lost ones’. In his own 1980 book The Meaning of Conservatism, Scruton argued that liberalism, economic or otherwise, was no less than the ‘principal enemy of conservatism’, adding that democracy itself can be ‘discarded without detriment to the civil well-being as the conservative conceives it’. In 1982, he founded a magazine, the Salisbury Review, to promote reactionary ideas, and, in particular, ideas of nation and race.

Converted to conservatism by his horror at the May 1968 student uprising in Paris (which he witnessed), Roger Scruton came to public prominence as a member of the Peterhouse school of high-church Conservatives associated with the Cambridge college, many of whom were alarmed by Margaret Thatcher’s commitment to free market economics and the rhetoric of liberty, which they felt downplayed traditionalist Conservative beliefs. So Maurice Cowling’s introduction to the 1978 Conservative Essays (to which Scruton contributed) insisted that ‘the sort of freedom’ that conservatives want is a freedom ‘that will maintain existing inequalities or restore lost ones’. In his own 1980 book The Meaning of Conservatism, Scruton argued that liberalism, economic or otherwise, was no less than the ‘principal enemy of conservatism’, adding that democracy itself can be ‘discarded without detriment to the civil well-being as the conservative conceives it’. In 1982, he founded a magazine, the Salisbury Review, to promote reactionary ideas, and, in particular, ideas of nation and race.

The magazine was launched in 1982, the year of the Falklands campaign, which followed the Brixton and Toxteth riots of the summer before. Its first edition (Autumn 1982) ran an article by Cambridge don John Casey, titled ‘One Nation: The Politics of Race’, attributing the popularity of the Falklands campaign to the fact ‘the Falklanders were British by every conceivable test’. He went on to claim that ‘there is no way of understanding English patriotism that averts its eyes from the fact that it has at its centre a feeling for persons of one’s own kind.’

Later in the article Casey moved on to the lessons he drew from Brixton and Toxteth: ‘There are various specific features that may lead us to suppose that the West Indian community, especially the Jamaicans, and above all those actually born in this country, is structurally likely to be at odds with English civilisation. There is an extraordinary resentment towards authority – police, teachers, Underground guards – all authority. This anarchic attitude seems to spill over so readily into an antagonism against Britain itself.’ He went on to cite ‘the involvement of West Indians in a vastly disproportionate amount of violent crime’. On this topic he concluded: ‘I do not wish to say that the problem about the West Indian community is just a problem about the possible destruction of civilised life in the centres of the big cities. (Although that is what is happening.) It is also that all this offends a sentiment – a sense of what English life should be like, of how the English behave towards duly constituted authority, a sense of what is civilised behaviour.’ Casey was kinder to the ‘Indian communities’ (‘intelligent, industrious, peaceable’) but nonetheless argued that their ‘profound difference of culture’ made them ‘most unlikely to wish to identify themselves with the traditions and loyalties of the host nation’. The existence of a community of ‘say, five to seven million persons’ who ‘cannot instinctively identify themselves with the State will call the actual constitution into question.’

The next section, headed ‘What is to be Done?’ concluded that ‘the only radical policy that would stand some chance of success is repatriation of a proportion of the immigrant and immigrant-descended population.’ However, if voluntary, ‘the whole process might be out of political control’. He went on:

‘The alternative is generally considered unthinkable in polite society: This would be retrospectively to alter the legal status of the coloured immigrant community, so that its members became guest workers – analogous to the Turks in Germany and Switzerland – who would eventually, over a period of years, return to their countries of origin.’

Aware, no doubt, that he was proposing a policy of compulsory repatriation then only advocated by the National Front, Casey acknowledged that these ideas ‘will seem abhorrent to many. My defence is this: the state of nationhood is the true state of man.’

Intellectual imprimatur

It should be said that Casey long ago disavowed the article, describing it as ‘crazy and inhumane’. What of Roger Scruton? It might have been possible to defend printing Casey’s piece on the ground that Scruton didn’t know what it might say when he commissioned it (and wouldn’t want to censor it on the grounds of free speech). But Scruton and Casey were close collaborators, co-chairs of the Conservative Philosophy Group, for whom the piece was delivered as a talk the previous June. As an editor, Scruton could have distanced himself from the opinions in the article: an editorial acknowledged that ‘many who would identify themselves as conservatives, may find themselves challenged by the thoughts expressed in John Casey’s contribution’ (‘may’), but that, nonetheless, ‘we hope to carry similar articles in future issues’. In a later edition (Summer 1983), Scruton wrote that: ‘As John Casey argued in our first issue, the cumulative effect of unwise immigration laws can no longer be ignored. While we may disagree with the policy of compulsory repatriation – ‘ ( note, again, the ‘may’) ‘a policy which Casey at least entertained, whether or not he wished finally to recommend it – there is no doubt that, merely to arrest the flow of immigrants cannot solve the problem’. It was hardly – to put it mildly – a ringing renunciation.

Over the following ten years, the Salisbury Review continued to publish articles on race, including a number by Ray Honeyford, the Bradford headmaster whose first Salisbury Review article (in which he criticised the ‘hysterical political temperament’ of the parents at his multiracial school) led to his taking early retirement. Scruton’s editorials continued to promote nationalist ideas (‘national consciousness provides, therefore, one of the strongest experiences of the immanence of God’). In view of the recent controversy, it’s worth noting an editorial of July 1985, in which Scruton argued that ‘A concern for social continuity prompts us to view not only promiscuity but also homosexuality as intrinsically threatening’.’ Later in the same piece he accused the Inner London Education Authority of portraying homosexuality ‘not as an abnormality, a weakness or a degradation, but as one among many harmless options’, clearly implying that he disagreed with this position. After all, he had just stated that ‘some desires ought not to exist’. (It should be said that in 2010, Scruton told the Guardian that ‘although it’s such a complicated thing’, he ‘wouldn’t stand by’ his earlier view that homosexuality was repellent. Well, good.)

Over the following ten years, the Salisbury Review continued to publish articles on race, including a number by Ray Honeyford, the Bradford headmaster whose first Salisbury Review article (in which he criticised the ‘hysterical political temperament’ of the parents at his multiracial school) led to his taking early retirement. Scruton’s editorials continued to promote nationalist ideas (‘national consciousness provides, therefore, one of the strongest experiences of the immanence of God’). In view of the recent controversy, it’s worth noting an editorial of July 1985, in which Scruton argued that ‘A concern for social continuity prompts us to view not only promiscuity but also homosexuality as intrinsically threatening’.’ Later in the same piece he accused the Inner London Education Authority of portraying homosexuality ‘not as an abnormality, a weakness or a degradation, but as one among many harmless options’, clearly implying that he disagreed with this position. After all, he had just stated that ‘some desires ought not to exist’. (It should be said that in 2010, Scruton told the Guardian that ‘although it’s such a complicated thing’, he ‘wouldn’t stand by’ his earlier view that homosexuality was repellent. Well, good.)

Of course, all of this was a long time ago. However, it provides a challenge to the emergent view of Scruton as a harmless old fogey, martyred by the liberal thought police. Ideas have consequences. In 1978, Mrs Thatcher made it clear that she saw immigration as a problem to be solved (‘People are really rather afraid that this country might be rather swamped by people with a different culture’). Had John Casey’s proposal been taken up, it would have led to the forced deportation of millions of people, including the parents and grandparents of people Scruton now sits on panels with and passes in the street. And any programme of voluntary repatriation, implicitly favoured by Scruton (‘there is no doubt that, merely to arrest the flow of immigrants cannot solve the problem’) would create an environment vastly more hostile than that advocated by Theresa May. Like their regular contributor Enoch Powell, one of the Salisbury Review’s missions was to give a lofty, intellectual imprimatur to anti-immigrant ideas, at a time (the 1980s) when such ideas were being given expression on the streets in the racist thuggery of the National Front. On the politics.co.uk website, Jonathan Portes argued that there are ‘direct links’ between Scruton’s views and those of Tommy Robinson and Gerard Batten. To support this, Portes quotes a 2006 article (in defence of Enoch Powell’s ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech) in which Scruton claims (completely erroneously) that ‘the stock of “social housing” once reserved for the indigenous poor is now almost entirely occupied by people whose language, customs and culture mark them out as foreigners’.

As stated, John Casey has disavowed his article. A reasonably rigorous search hasn’t revealed whether Roger Scruton ever disavowed his decision to publish it. Why didn’t the New Statesman ask him?

Thank you for this, David. Some of us, including yourself, were alert to this at the time, as evidenced by the essays in The Ideology of the New Right. Scruton’s own views in The Nature of Conservatism were deeply reactionary and implicitly exclusionary. I find it hard to understand why he is being given credence in relation to sustainable prosperity as a respectable philosopher.