A resurgent media fixation with the 1980s Bradford headmaster Ray Honeyford has created a space for New Right ideas about cultural deficit within BME communities to resurface.

‘Whatever you thought of him, he was certainly ahead of his time.’ That, in sum, is what it took Aasmah Mir twenty-eight minutes to say in her recent Radio 4 broadcast, produced by Martin Williams, on The Lessons of Ray Honeyford. Recounting the intense, bitter furore surrounding the Bradford headteacher for a few years in the 1980s, the ‘Honeyford affair’, she argued, has come to represent ‘a kind of contemporary parable’ when looked at some three decades later. It ‘is a story upon which different people have different claims’, Aasmah Mir suggests, ‘[with] its meaning chang[ing] depending on who is telling it’. And she is assiduously fair in her attempts to portray them. Equal weight was given in the programme to competing perspectives on a man described as a hero for the Right and hate figure for the Left. Her quintessentially liberal account, however, is unfortunately devoid of any historical or contemporary meaning. And as such is little more than an appendage to the ongoing revisionist attempt to rehabilitate Honeyford.

The headteacher who pulled no punches

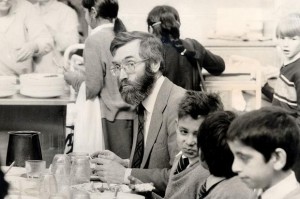

Honeyford became the head of Drummond Middle School in Bradford at around the same time that the policy of ‘bussing’ children in the area was ended. As a result, the pupil intake of his school quickly came to represent the catchment area that it served: almost entirely Pakistani. He was reprimanded in 1982 for writing a letter of complaint to the local press, on school-headed paper, about the opening of a West Indian community centre. But, undeterred, he wrote a series of letters and articles – many of which were published by the Times Educational Supplement – questioning what he called ‘multiracial myths’ and attacking educational practices around multiculturalism which, he said, encouraged children to retain their identities at the expense of a shared British identity. That is why he is now seen as the tribune by those who adhere to the ‘parallel lives’ thesis.

By the time he came to write for the then little-known Conservative journal The Salisbury Review, in 1984, Honeyford’s ‘lifelong left-wing sympathies’ had been jettisoned. His infamous article ‘Education and race – an alternative view’ catapulted him into a bitter, protracted dispute with the council and the parents of the children he was teaching. As The Lessons of Ray Honeyford points out, this article continued the trajectory of his previous writings, but also pulled no punches where his prejudices were concerned. He wrote of his encounter with a ‘half-educated and volatile Sikh’; he described Pakistan, ‘despite disproportionate western aid’, as ‘obstinately backward’; he explained how West Indian homes ‘lacked educational ambition’. The ‘echoes’ of this article were ‘deafening’: the setting up of a parent action committee demanding the termination of his employment; children withdrawn from the school and an alternative (short-lived) one set up in its place; his suspension and later reinstatement, before being paid-off to take early retirement. As the programme explains, Honeyford never taught again.

What the programme did not do, however, was put the issue Honeyford ‘exposed’ in a context. No doubt a school of working-class Pakistani-descended children was a challenge to an orthodox Yorkshire teacher.  But how areas of Bradford became segregated through racist housing policies was not explored. Neither were we told how other educationalists were meeting such challenges. A head down the road in Sheffield, for example, was meeting diversity by involving the community in the school, reflecting the concerns of different communities in the governance, giving parents a stake in their children’s futures. Contrast this with Honeyford’s decision to fire off letters which went well beyond a reasoned critique of culturalist policies, and descended into abuse and stereotypes which revealed a profound animosity towards the communities from which his pupils were drawn. Honeyford defined the problem as the culture of the children in his care. And this premise was taken on without question.

But how areas of Bradford became segregated through racist housing policies was not explored. Neither were we told how other educationalists were meeting such challenges. A head down the road in Sheffield, for example, was meeting diversity by involving the community in the school, reflecting the concerns of different communities in the governance, giving parents a stake in their children’s futures. Contrast this with Honeyford’s decision to fire off letters which went well beyond a reasoned critique of culturalist policies, and descended into abuse and stereotypes which revealed a profound animosity towards the communities from which his pupils were drawn. Honeyford defined the problem as the culture of the children in his care. And this premise was taken on without question.

Thus the programme suggested that the ‘affair’ was far more than just a dispute about a headteacher expressing views which offended and alienated many Asian and black parents. ‘It started a debate about multiculturalism and integration that we are still having.’ And from this standpoint, Honeyford asked valid questions about how best ‘to teach in a school where there are several different cultures’, but it was just the way he asked them was counter-productive. Style overshadowed content in a row which ended up distracting from what were vital issues about the role of education and the creation of core, British, values. ‘What offended many wasn’t necessarily his ideas’, the programme said, ‘it was the careless way he expressed himself’. This is becoming an accepted orthodoxy of the Honeyford affair, echoed, for example, by the Guardian’s Ian Jack a few months ago when he suggested that ‘it’s hard not to think he was right or, if you prefer it more neutrally, well ahead of his time’. This Ray Honeyford was ‘right’ line is in fact being pushed by a whole group of rightwing backers.

Resurrected by the Right

Just as Enoch Powell (another man accused of mucking up his bona fide message with the wrong medium) had his followers who would proclaim him as a seer every five years or so, so, too, now does Honeyford. Over the last few years, there has been a renaissance of support from libertarian, rightwing and conservative thinkers for Honeyford, seeking to restore his place in history, as well as establish his relevance for the present. These accounts seek to portray the headteacher as a man whose warnings speak still to today’s realities. For the Right – and to certain elements of those who describe themselves as the apostate Left – Honeyford has been vindicated.

Upon his death in 2012, the Daily Mail’s Abhijit Pandya described him as a man who ‘warned us about the harm to national identity multiculturalism would cause’. ‘It is time’, he proclaimed, ‘that we stop hounding men such as Honeyford and Powell. Men who understood the problems of mass-immigration without assimilation.’ Author Leo McKinstry, meanwhile, in the same paper, argued that Honeyford ‘predicted that, without a unifying sense of national identity, we would become an ever-more divided country, which is exactly what has occurred. Large parts of urban Britain are increasingly split along racial lines, with many Britons now feeling like aliens in their own land.’

What these eulogies share is the idea that Honeyford was a man ahead of his time: a prophet who spoke truth to a world too blinded by political correctness to see it. When they claim that he has been vindicated, they are claiming that his apocalyptic, dystopian views have been proven correct. Deftly sidestepping the fact that the Right waged a ferocious campaign of support for him at the time (especially in the press) they maintain that he was some kind of truth-telling David, up against an anti-racist Goliath.

Last year Ed West, in his book the Diversity Illusion, argued that the Honeyford affair ‘showed that all debate over race and immigration had been shut down, and that the merest suspicion of “racism” turned off rational facilities. A race allegation could be as damning as a rape allegation.’[1] Demos director David Goodhart maintained in his 2013 book The British Dream that Honeyford was ‘denounced’ for ‘what now seem prescient views (if somewhat offensively articulated)’, claiming that white ‘liberals and leftists’ set aside their ‘liberal principles … in the name of cultural and ethnic difference.’[2] For author Peter Hitchens, he was destroyed by a ‘liberal revolutionary agenda’ – ‘driven from his job and of course condemned as a “racist”’. These thinkers parrot what Honeyford and his supporters maintained at the time: that he was the victim of a state-sanctioned witch-hunt. The word ‘racism’, Honeyford claimed, ‘is the icon word of those committed to the race game. And they apply it with the same sort of mindless zeal as the inquisitors voiced “heretic” or Senator McCarthy spat out “Commie”’.

Now his ideas find traction

All of this is well known, of course. None of this is new. But the point is that the resurgence of support for Honeyford is not merely about the man, but indicates a broad level of support now for the ideas with which he was associated then. Honeyford found an ideological home in the coterie of journalists and ‘thinkers’ associated with the ‘New Right’. And through the revival of Ray Honeyford, what is also being revived is the New Right’s philosophies, the New Right’s vision, the New Right’s basic concerns, ‘to uphold traditional authority and morality and to preserve the British nation from what they regard as the triple perils of cultural decline, black immigration and a breakdown of law and order.’[3]

A few months ago, in yet another article claiming Honeyford had been vindicated, New Right philosopher Roger Scruton (editor of the Salisbury Review in the 1980s when Honeyford wrote for it) did little to challenge such a view, stating that Honeyford was ‘defending a social order founded on secular law and national loyalty’. According to Scruton, Pakistani families attending Drummond Middle School threatened this. ‘The idea’, he asserted, ‘that their children might be integrated into our kafir society was anathema to them, and they saw the school to which they were legally obliged to send their children as a thing to be either subverted or destroyed.’

in yet another article claiming Honeyford had been vindicated, New Right philosopher Roger Scruton (editor of the Salisbury Review in the 1980s when Honeyford wrote for it) did little to challenge such a view, stating that Honeyford was ‘defending a social order founded on secular law and national loyalty’. According to Scruton, Pakistani families attending Drummond Middle School threatened this. ‘The idea’, he asserted, ‘that their children might be integrated into our kafir society was anathema to them, and they saw the school to which they were legally obliged to send their children as a thing to be either subverted or destroyed.’

Like Honeyford, his supporters see themselves as part of a battle in which inferior alien values are pitted against their superior ones. They want to see anti-racism abolished. Multiculturalism is a threat to the UK, national homogeneity needs defending at all costs. When accounts of the Honeyford affair, such as the supposed even-handed Mir broadcast, assert that his ideas were ahead of their time, what they actually show is that such New Right culturalist and nativist ideas – once confined to the fringes of the Right – are now, some three decades later, gaining a hold in the political and cultural mainstream.

RELATED LINKS

Read an IRR story: ‘The beatification of Enoch Powell‘

Read an IRR story: ‘Goodhart, bad analysis‘