A long-term resident of North Kensington recalls the area’s social history as representative of momentous Black British community struggles.

Beyond memorialising the lynch-murder of Kelso Cochrane on 17 May 1959, we have to look at the history that surrounds it. New arrivants to fashionable twenty-first-century Notting Hill, along with new generations of long-standing residents, will have next to no idea of the social history of the space that they now inhabit around the northern end of the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, London’s richest. They will know little or nothing of the area’s working-class ‘slum lands’ of the 1940s and 1950s; of the incoming Caribbean migrants who, from the late 1940s through the ‘50s and ‘60s, had to deal with unscrupulous Rachman-plus landlords; of the Empire Loyalists and other fascist and racist organisers, headed by Oswald Mosley and Colin Jordan, who stirred race hate among poor Whites, sparking the attacks that flared up into the historic Notting Hill riots of 1958 in ‘the Grove’; of the Black community’s protest and fight back, and its subsequent refusal to stomach prejudice and crude discrimination in the neighbourhood – all of which contributed to the defining of ‘the Grove’ as a local community and cultural space that transcended ‘race’.

The wealthy new residents, accompanied by the gold rush of their property- dealing estate agents, know nothing of the history – even if it is that very history that they now buy into when they come to ‘the Grove’ (their ‘Notting Hill’) with its wonderful, sophisticated, cosmopolitan ‘vibe’.

But more than merely contributing to a marketable ‘vibe’ for wealthy middle-class incomers, the Grove’s social history is representative of the momentous Black British community struggles in the second half of the 20th century; Black struggles that joined and rejuvenated the fight of the entire working class in the UK against injustice and impoverishment, and forced anti-racism on to the nation’s change agenda.

Let me provide some bullet points in regard to the Black rebel history of ‘the Grove’. A fuller, more detailed telling can be found in Sivanandan’s seminal 1981 essay ‘From resistance to rebellion: Asian and Afro-Caribbean struggles in Britain’.

1958 ‘riots’

In the summer of 1958, the Black fight back against racist attacks in the course of what has come to be known as the Notting Hill riots, signalled a militant refusal to take any more nonsense, as well as a call to other communities across the UK to stand together in order to resist further racist attacks. Whiteness would have to adjust its attitude to Blackness. In time, heroic progressive people’s lawyers like Gareth Peirce and Ian Macdonald, would cut their teeth and find their feet in support of community activism in the Grove.

Women organisers

Out of the 1958 mobilisation for the antiracist fight-back came The West Indian Gazette (WIG) – the first post-world war two British Black newspaper. The WIG could well have been dreamed up in the Grove by Claudia Jones, (now an acclaimed heroine of twentieth-century Black British struggle), who would have been welcomed to the Grove by the equally significant Amy Ashwood-Garvey who had her house at 1 Bassett Road.

Amy Ashwood-Garvey was the first of the two Amy’s serially married to the pre-eminent pan-Africanist Marcus Garvey. Marcus Garvey was the founder and leader of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) – the largest global mass organisation in Black African political history. And Amy Ashwood-Garvey had been central to the organising secretariat of the 1945 watershed Pan-African Congress held in Manchester, England.

The Carnival

The first Caribbean carnival celebrations in London, held indoors, were explicitly promoted as a response to the 1958 ‘riots’ and the lynch-murder, in the Grove, of Kelso Cochrane in 1959. This was another initiative of Claudia Jones, using her West Indian Gazette as an organising tool. Along with others, Claudia Jones took a justice for Kelso campaign to the Home Office. No one was ever arrested or prosecuted for Kelso Cochrane’s murder.

The first Caribbean carnival celebrations in London, held indoors, were explicitly promoted as a response to the 1958 ‘riots’ and the lynch-murder, in the Grove, of Kelso Cochrane in 1959. This was another initiative of Claudia Jones, using her West Indian Gazette as an organising tool. Along with others, Claudia Jones took a justice for Kelso campaign to the Home Office. No one was ever arrested or prosecuted for Kelso Cochrane’s murder.

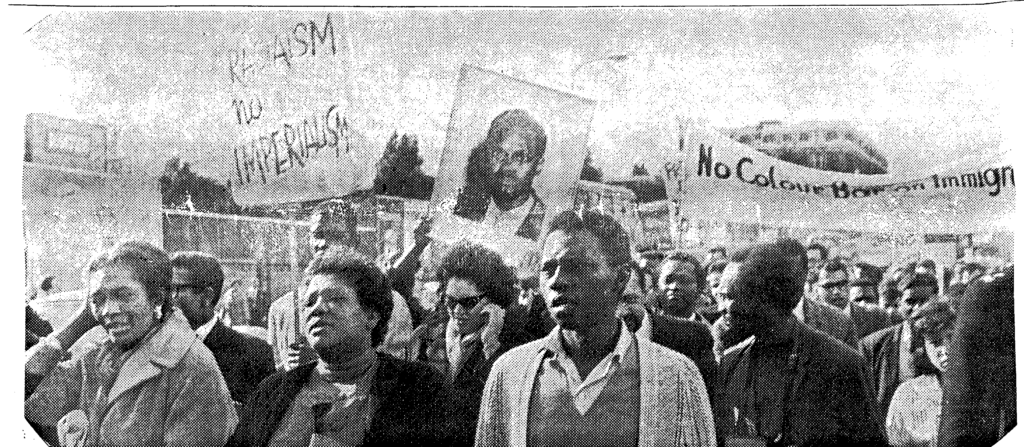

No Colour Bar

In early 1962, part and parcel of a ‘No Colour Bar’ campaign initiated by war resister and left Labour MP, Fenner Brockway, Claudia Jones also founded the Conference of Afro-Asian-Caribbean Organisations (CAACO), which evolved from the Coloured People’s Progressive Association. CAACO was formed to fight against the first restrictive Commonwealth Immigrants Bill – overtly racist legislation which ended free movement from the (Black) Colonies and effectively said that unless Commonwealth citizens had a ‘family connection to the UK’ (i.e. White heritage) they could in future not enter without a specific entry work- or study-related voucher.

We Shall Overcome

And in August 1963, it was CAACO that organised a London demonstration (in solidarity with Martin Luther King’s historic ‘People’s March’ on Washington) and Black and White people moved off from the Grove and marched on the US embassy in Grosvenor Square. Pearl Prescod, actress-singer and Grove resident of Cambridge Gardens, organised with and marched next to Claudia, singing the adopted civil rights anthem ‘We Shall Overcome’. She was my mother. I was there – a teenager.

RAAS

In 1965 another leading ‘rebel’ organisation, the Racial Action Adjustment Society (RAAS) was formed by Grove militant Michael De Freitas (who, inspired by the African-American radical Malcolm X’s visit to London, changed his name to Michael X). RAAS was led by Michael De Freitas and Roy Sawh – both stridently militant and not afraid to use the threat of a violent fight-back to intimidate would be racist attackers.

In 1965 another leading ‘rebel’ organisation, the Racial Action Adjustment Society (RAAS) was formed by Grove militant Michael De Freitas (who, inspired by the African-American radical Malcolm X’s visit to London, changed his name to Michael X). RAAS was led by Michael De Freitas and Roy Sawh – both stridently militant and not afraid to use the threat of a violent fight-back to intimidate would be racist attackers.

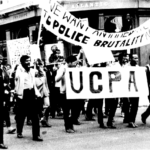

UCPA

Then, in 1967, a sister organisation to RAAS, the revolutionary-socialist Universal Coloured Peoples’ Association (UCPA) was forged by another Grove associate, Obi Egbuna – an essayist and playwright and one of many intellectuals, writers and theatre people who regularly visited my mother’s home in Cambridge Gardens in the early 1960s. Indeed, my mother and a number of other London based Caribbean and African actors performed Obi’s play ‘Wreath for Udomo’ at FESTAC in Dakar Senegal in 1966. The UCPA set up study groups about the country, as well as a ‘Free University for Black Studies’ with a base in the Grove. The UCPA foreshadowed the UK’s ‘Black Panther Movement’, founded by Obi Egbuna, and later led by Altheia Jones-Lecointe who would become one of the Mangrove Nine in later Grove history.

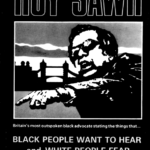

The UCPA, along with RAAS, was so stridently militant that several of its leading voices, including Obi Egbuna and Roy Sawh, were arrested, jailed, prosecuted and fined for, of all things, incitement to racial hatred. Irony of ironies – they were amongst the first people to be arrested under the then new race relations legislation.

The UCPA, along with RAAS, was so stridently militant that several of its leading voices, including Obi Egbuna and Roy Sawh, were arrested, jailed, prosecuted and fined for, of all things, incitement to racial hatred. Irony of ironies – they were amongst the first people to be arrested under the then new race relations legislation.

Black – a political colour

It is not insignificant that, against all the racialised divide-and-rule strategies of the White colonial order, RAAS and the UCPA, (as with Claudia Jones’ CAACO before them), defined ‘Black’ as a political colour, inclusive of Asians, Caribbeans and Africans – united by their historical humiliations, under racist White colonialism, as ‘coolies’, ‘slaves’, and ‘savages’, respectively. And let us not pretend that those divisions and animosities amongst the ex-colonised and what are now called ‘people of colour’ have disappeared even today.

Black activist self-help

The late 1960s and early 1970s also saw the emergence of a number of local, activist, self-help organising centres in the Grove, which provided much-needed advice and support to Grove residents encountering, and confronting the authorities over discrimination in schooling, housing, policing and judicial proceedings. Chief amongst these organisations were ‘Back-a-yard’, which became the Black People’s Information Centre (BPIC) on Portobello Road; ‘Grassroots Storefront’ in Golborne Road; and, the ‘Mangrove’ on All Saints Road. ‘Grassroots’, founded on pan-Third World principles, published a regular Black Liberation Front (BLF) information bulletin-cum-newspaper. And, although mainly White staffed, the first people’s neighbourhood law centre in the UK, the North Kensington Law Centre, set up in Golborne Road, would have been prompted in part by these ‘rebel’ Black initiatives. Today there is nothing to mark the sites of these historic life-blood community supports.

The late 1960s and early 1970s also saw the emergence of a number of local, activist, self-help organising centres in the Grove, which provided much-needed advice and support to Grove residents encountering, and confronting the authorities over discrimination in schooling, housing, policing and judicial proceedings. Chief amongst these organisations were ‘Back-a-yard’, which became the Black People’s Information Centre (BPIC) on Portobello Road; ‘Grassroots Storefront’ in Golborne Road; and, the ‘Mangrove’ on All Saints Road. ‘Grassroots’, founded on pan-Third World principles, published a regular Black Liberation Front (BLF) information bulletin-cum-newspaper. And, although mainly White staffed, the first people’s neighbourhood law centre in the UK, the North Kensington Law Centre, set up in Golborne Road, would have been prompted in part by these ‘rebel’ Black initiatives. Today there is nothing to mark the sites of these historic life-blood community supports.

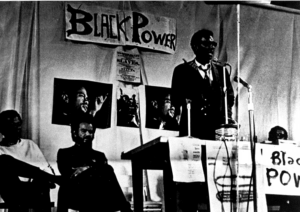

Black Power

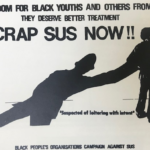

All of those organising centres were influenced and fuelled by the Black Power fight-back ideologies of the day. And all were standing up for ‘the youth’ – the first generation of Black young people born and mis-educated here post WW2 – then facing, amongst other everyday discriminatory frustrations, an outrageous police ‘sus’ offensive.

Police forces, up and down the land, had unearthed and dusted off an old nineteenth-century law and used it to target, regularly accost, and often arrest Black youth on suspicion that they were likely or about to commit crimes!! The ‘sus’ legislation and police practice were exposed and embarrassed by insistent political protest to the point of being taken off the books – even if, as many noted, the same provisions were almost immediately reinstalled in new police powers legislation. Today something of that discriminatory ’sus’ practice survives in what we now refer to as police ‘profiling’.

Rastafari

The other major influence on the militant ‘vibe’ in the early 1970s ‘rebel’ Grove was Rastafari – who established important ‘12 Tribes’ and ‘Nyabinghi’ chapters located here, and stirred the emergence of ‘metropolitan reggae’ with the Grove as a major centre. ASWAD and Sons of Jah were amongst a number of notable Grove reggae pioneers of the period.

In the same moment of the early 1970s, drawing on and reflecting the spirit of all the struggles/history of the Grove, the Caribbean-roots Carnival, which had come out of the indoor venues, took root in the streets. In a way the Carnival is the Grove’s living monument to its long social struggle against racist bigotry and for civilised, cosmopolitan ‘livity’ as the Rastafari say it. Hardly remembered now is the fact that in the early days, the Carnival hosted tens of street stalls set up by community campaigns and political groups.

Remembering ‘rebel’ history

The transformational resistance that we see in the Grove’s ‘rebel’ history, in the decades immediately following the 1958 ‘riots’ and the 1959 racist murder of Kelso Cochrane, is joined by similar community militancy in other parts of London, and indeed other parts of Britain. New generations need to read and be reminded of this ‘rebel’ history – with its anti-racist, womanist, internationalist, and socialist drivers.

Our ‘Grove’, their Notting Hill

Beyond the early 1970s, the substantial community that set up the liberated Grove ‘vibe’ suffered dispersal, the weakening of its drive, and the corruption of its potential. There followed a ‘cleansing regeneration’, a state blitz that, in effect, handed the liberated Grove ‘vibe’ eventually to new incomers with loads of disposable income. Our Grove became their Notting Hill.

Beyond the early 1970s, the substantial community that set up the liberated Grove ‘vibe’ suffered dispersal, the weakening of its drive, and the corruption of its potential. There followed a ‘cleansing regeneration’, a state blitz that, in effect, handed the liberated Grove ‘vibe’ eventually to new incomers with loads of disposable income. Our Grove became their Notting Hill.

The urgency of struggle today

Today the scandal of disproportionate Black working-class ‘exclusions’ from schools bears a disturbing resemblance to the 1970s state abandonment of West Indian children labelled ‘educationally sub-normal’. The over-representation of Black youth in prisons, borstals and mental health institutions looks like something, now institutionalized and continuous with the humiliations of that era. And early twentieth-century media panics about urban knife and gun crime – the violence of the violated – would wash the establishment’s hands of responsibility for the systematic extinguishing of hope, and consequent alienation of substantial sections of this youth.

So, for all that promising 1950s-1970s history of resistance, challenge and transformation, the predicament of brutalised and alienated Black working-class youth today, and the resurgence of racism and indeed fascism in Britain as across Europe, do not allow us to be triumphalist about past struggle successes. The need to engage in today’s versions of the old struggles is arguably as urgent as it was in the days of Kelso Cochrane’s murder sixty years ago.

Colin Prescod’s keynote for ‘Festival of Dissent’ – Kelso Cochrane’s murder memorial event 60 years on, Kensal Library, 15 May 2019.

Images from the IRR’s Black History Collection.

Thank you Colin for this important history lesson!

Excellent history lesson.

However, the Jones/WIG carnival of 1959 was not London’s first Caribbean carnival, nor was the WIG the first post-world war 2 British Black newspaper – they both have less known precursors. These are the sort of things I flag up in my upcoming book ‘Disrupting African British History’.

Also Brent has a claim on the group Aswad, as some of its members grew up in Brent, the capital of reggae in Britain!