An exhibition that bears witness to migrant deaths in the Mediterranean challenges us to confront the UK’s complicity in Europe’s war on asylum.

Two image-events bookended Refugee Week 2019. The first was artist-provocateur Christoph Büchel’s ‘installation’ of the migrant shipwreck known as The Boat of Innocents in Venice’s Arsenale. Rechristening it Barca Nostra (Our Boat) was no doubt Büchel’s way of acknowledging European culpability for the deaths of at least 800 people when it capsized in April 2015. But valid criticism of the project centred on its cost – reportedly in the tens of millions – and his rash insistence on presenting it without comment and lack of any strategy to engage passersby (locals, tourists, Biennale-goers). The second ‘event’ was the front-page photo of a Salvadoran father and daughter, Óscar and Valeria Ramirez, lying face-down, dead and drowned, a kilometre from the Texan border. For those already aware of the consequences of United States border violence, it prompted critical ethico-political questions regarding the circulation and consumption of the deaths of ‘others’ as spectacle.

There must be alternative ways of seeing that resist the logic of dehumanisation and also avoid diminishing the enormity of the ongoing calamity. Some of these can be found in Sink Without Trace, an exhibition on migrant deaths in the Mediterranean, hosted by Euston’s P21 Gallery. Succeeding two previous exhibitions on the subject in Gateshead (2017) and York (2018), it’s the most comprehensive in Britain yet, displaying work by eighteen artists from ten different countries in a variety of forms. Thankfully, the curators are conscious of art’s limits. One of them, artist Maya Ramsay, asks in the exhibition booklet: ‘Are audiences being encouraged through art to campaign for change in migration policies or is there simply an empathetic response followed by inaction? How much of what we are doing as artists and curators has any real impact on those that we are making the work about?’ What follows is an attempt to situate the exhibited works historically and politically, in the hope that those who see them come away with a better sense of what’s at stake in Europe and the Mediterranean.

The UK in and out of Europe

Since 2015 especially—though there are precedents going back decades—the European Union and its member states have taken increasingly extreme measures to prevent refugees and migrants from reaching Europe via the Mediterranean. It’s a deliberate political project that has cost thousands of lives, as a group of international lawyers recently charged. Those who succeed in crossing, if they aren’t deported, are subject to multiple overlapping forms of state and popular racism, as well as exploitation. In Britain, the domesticated borders of the ‘hostile environment’ have been challenged on many fronts since the Windrush scandal. Meanwhile, Britain’s highly-securitised external borders, its relationship of convenience with ‘Fortress Europe’, and its role in perpetuating a ‘global framework of massive injustice’, remain less understood and thus harder to oppose.

Since 2015 especially—though there are precedents going back decades—the European Union and its member states have taken increasingly extreme measures to prevent refugees and migrants from reaching Europe via the Mediterranean. It’s a deliberate political project that has cost thousands of lives, as a group of international lawyers recently charged. Those who succeed in crossing, if they aren’t deported, are subject to multiple overlapping forms of state and popular racism, as well as exploitation. In Britain, the domesticated borders of the ‘hostile environment’ have been challenged on many fronts since the Windrush scandal. Meanwhile, Britain’s highly-securitised external borders, its relationship of convenience with ‘Fortress Europe’, and its role in perpetuating a ‘global framework of massive injustice’, remain less understood and thus harder to oppose.

Polarised opinion on Brexit can sometimes obscure the EU’s fundamentally exclusionary nature. Remainers exalt it as the guarantor of internationalism and multiculturalism while leavers condemn it as the borderless supra-state allowing mass immigration to push Britain to ‘breaking point’. That last phrase appeared on a notorious UKIP campaign poster in June 2016, captioning a photograph of a long queue of non-European migrants at the Croatia-Slovenia border. Unmentioned was the fact that passage across the Balkan corridor had been severely restricted by those two EU countries just months earlier. Indeed, free movement within the Schengen Area has always been coupled with strong external borders, including pernicious externalisation agreements with countries in the ‘global south’, while over the past few years controls at internal European borders have also intensified. This architecture of deterrence and containment is designed to render the struggle of refugees and migrants, and Europe’s ‘unknown war’ on them, invisible.

Europe’s unknown war

Sink Without Trace begins in 2011—the ‘deadliest year’ in the Mediterranean since its records began, the UN Refugee Agency declared at the time. On 27 March, only two weeks after NATO’s intervention in Libya, seventy-two migrants set sail from war-torn Tripoli; after running out of fuel, they drifted helplessly for fourteen days before being borne all the way back with only nine survivors. In their report on the ‘left-to-die boat’—presented in video form at the exhibition—the Goldsmiths-based research collective Forensic Oceanography (FO) combine information derived from official sources and sophisticated geo-spatial technologies (the view from above) with the testimony of survivors (the view from below), to prove that the latter’s fate was not the result of fortuitous oversight but of callous non-assistance by several actors (national, supra-national and commercial). Accordingly, in his intimidating Annex canvasses, artist Mario Rossi maps a Mediterranean sea that is simultaneously a turbulent expanse that kills and a controlled political space governed by maritime bureaucracies for western military and trade interests.

FO’s subsequent reports detail the declension of European migration policy in the Mediterranean after 2011. Mare Nostrum (Our Sea), an unprecedented Italian search and rescue (SAR) operation, was launched in October 2013 after hundreds of migrants drowned in a widely-reported shipwreck off Lampedusa. But it was soon pilloried as a ‘pull-factor’ and, under EU pressure, consequently abandoned in November 2014. The ensuing ‘SAR vacuum’ was filled initially by commercial vessels that were ill-equipped for the job, however well-intentioned their crews. The ‘pull-factor’ argument was then redeployed to create a ‘toxic narrative’ around the NGO SAR missions that stepped in to counter the EU’s policy of non-assistance. Over the last few years, Italy – with EU backing – has revived and in effect taken full strategic and operational control over the Libyan Coast Guard, enlisting it to execute a policy of ‘refoulement by proxy’, effectively outsourcing its dirty work.

Asylum after empire

Where does the UK fit into this narrative? On one side of a canvas protest banner by English artist Victoria Burgher, A. Sivanandan’s defiant aphorism is reworked from the standpoint of white Britain: ‘they are here because we were there’. Quite literally, this reminds viewers that Britain colonised, occupied or invaded – in some cases very recently – many of the world’s largest refugee-producing countries. On the other side is a reproduction of the famous Brookes slave ship woodcut, a document of barbarism powerfully wielded by late-eighteenth-century abolitionists. The radical demand for open/no borders functions, in Britain, as both a humane response to a contemporary crisis and as an act of historical redress, acknowledging its roots in empire and its foundational role in racial capitalism.

Many migrants set out with Britain as their ultimate destination – because of historical or familial ties or, rightly or wrongly, its reputation as a haven compared to less tolerant and economically stable European countries. But the obstacles they must overcome to reach it are stupendous. In London-based artist Aida Silvestri’s Even This Will Pass photograph series, the blurred faces of Eritrean migrants to Britain are inscribed with the jagged cartography of their journeys. The difficulty of reaching Britain is not a natural outcome of its ostensible geographical distance and isolation. Since the early 1990s, the UK has extended a sophisticated system of ‘juxtaposed controls’ to checkpoints in France and Belgium. The few who attempt the alternative route across the Channel are dismissed a priori as ’illegals’. When the EU Border Agency (Frontex) was established in 2005, the government sought full participation. Europe’s unknown war is Britain’s too.

Barca Nostra?

The exhibition’s one intervention in public space occurs on nearby Regent’s Canal, where English artist Lucy Wood has moored a small migrant boat from Libya, aboard which thirty-six North Africans successfully reached Lampedusa in 2012. (This isn’t the first time it has come to Britain: in late 2013, Wood encouraged a group of politicians to make a short journey on it along the Thames, something repeated in similar fashion with a different boat by German SAR NGO Sea-Watch in Berlin in October 2015.) The boat’s preservation as a ‘floating museum’ is important because most such vessels are summarily hacked to pieces and burnt in Lampedusa’s ‘boat graveyard’, a process recorded in Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin’s film The Bureaucracy of Angels.

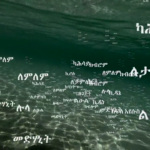

But what happens to the bodies of the dead? Max Hirzel’s photo series Migrant Bodies focuses on the rare occasion when the Italian government salvaged a migrant shipwreck – the very Barca Nostra that now sits in the Arsenale – in order to forensically identify victims and provide at least some form of accountability and closure. But the clinical, bureaucratic nature of the process fails to overcome what SA Smythe described as ‘the farce of the recurrent practice of enumeration, of counting people without being accountable to them’. In Asmat (Names), the Ethiopian refugee filmmaker Dagmawi Yimer, who founded the Rome-based Archive of Migrant Memory, substitutes naming for counting and calls European powers to account while doing so, offering an alternative form of memorialisation.

Refugee art

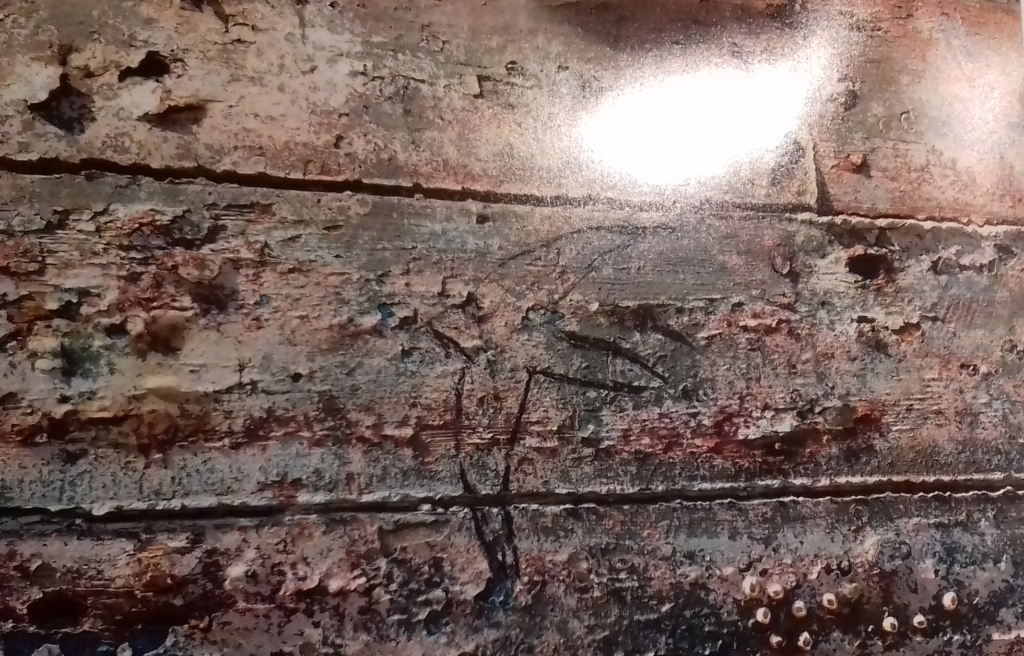

The curators have chosen to frame the exhibition around migrant deaths, foregoing more positive concepts like ‘resistance’ or ‘struggle’. Fortunately, there’s no reduction of these deaths to a matter of mere ‘bodies’, as sometimes occurs in work shaped by politico-aesthetic discourses of bare life and necropolitics. For the most part, as in Hirzel’s work, it’s not death itself that is the focus but the systemic factors that do or not make such deaths ‘grievable’. Ramsay’s graphite rubbings of unidentified Sicilian graves remind us that even those who don’t sink without trace still often remain only as persone sconoscitue (unknown persons).

In spite of death, the works by refugee artists – seven of the eighteen exhibited – are necessarily the products of survival, displaying an agency and vision that cannot be reduced to numbers or structural push-and-pull factors. The Kurdish refugee Shorsh Saleh’s miniature paintings of migrant boats in different situations – floating, capsizing, and even breaking through borders – are a particular highlight. Such works challenge a neo-colonial visual economy in which, as Susan Sontag remarked in Regarding the Pain of Others, the other is regarded ‘only as someone to be seen, not someone (like us) who also sees’. Unforgettable, above all, are Ramsay’s photographs of anonymous drawings on shipwrecked migrant boats. One shows the simple black outline of a bird, wings spread in flight – the symbol of life beyond borders.

Spectatorship or solidarity

A curated exhibition in a private metropolitan art gallery can’t ‘do justice’ to an issue of this gravity. Perhaps all that Sink Without Trace can achieve is, to quote Sontag once again, to ‘invite us to pay attention, to reflect, to learn, to examine the rationalizations for mass suffering offered by established powers.’ And, ideally, it wouldn’t end there. Those of us with citizenship and other privileges, who aren’t and won’t be compelled to cross seas to escape oppression and immiseration, should feel sympathy, compassion and anger. But more urgent is finding concrete ways to express and act in solidarity with those affected by border violence. Well before the photograph of 3-year-old Alan Kurdi shocked Europe into momentary compassion in September 2015, many ordinary Europeans were – and still are – busy engaging in a wave of voluntary solidarity efforts. In Britain, as in Europe, there remains much to be done.

Sink Without Trace is showing at P21 Gallery until July 13, with free entry. Proceeds from the exhibition go to Alarm Phone, a vital hotline for those crossing the Meditteranean.

This excellent website certainly has all the information I wanted concerning

this subject and didn’t know who to ask.