Drawing on a recently published report, Leaving the War on Terror: a progressive alternative to counter-terrorism policy, Arun Kundnani outlines why counter-terrorism policies do not work, and what an alternative could look like.

The starting point for this report goes back two years to a speech Jeremy Corbyn gave at Chatham House, in which he argued that “the war on terror is simply not working”. Opinion polling suggested a majority agreed. But there has been little discussion in Labour circles of what a progressive alternative to the War on Terror might look like. The ten of us who wrote this report have all been analysts of counter-terrorism policies over the last ten to fifteen years. I thought perhaps now is the time for us to think about what an alternative approach might be, to go from a reactive engagement with the policy-making process to directly advocating alternatives. What we’ve produced is the result of that thinking. We recognise the difficulty and complexity of the issue of terrorism and the various barriers that stand in the way of a different approach. But we believe the time is right to critically assess the legacy of the last twenty years and change course.

There are three parts to our argument. One, counter-terrorism policy does not work; two, why it does not work; and three, what an alternative would look like.

So, first, Britain’s counter-terrorism policies do not work. They do not work for the British people, who wish to live free of terrorism. They do not work for the various communities in the UK whose experience of counter-terrorism has been one of stigmatisation and criminalisation. And they do not work for the people of the Middle East, South Asia and Africa, whose human rights have been systematically violated in the War on Terror.

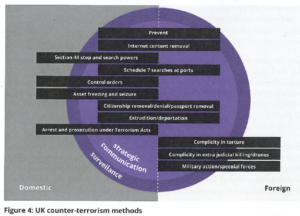

Twenty years ago, Tony Blair’s government introduced the first of the fifteen new Terrorism Acts that have been passed since then in what has become a near-annual parliamentary ritual. Each Act ratcheted up the powers available to the police and intelligence agencies, together creating a shadow world of state powers in which the legal rights espoused in the regular criminal justice system are set aside.

Since the late 1990s, the use of surveillance and propaganda has expanded and deepened; military force and extra-judicial killing have became routine methods of counter-terrorism; and complicity with torturers was normalised. The logic of counter-terrorism was spread to every sphere of public life in Britain as workers in government services were expected via Prevent policy to become the eyes and ears of national security surveillance – not to identify persons where there was a reasonable suspicion of criminal activity but according to a much vaguer category of ideological suspicion – effectively institutionalising Islamophobia in our public services. The definition of the threat was itself transformed: no longer simply a matter of individual acts of violence but a much broader danger, understood in terms of clashes of culture, ideology and values, implicating an entire generation of young Muslims.

Since the late 1990s, the use of surveillance and propaganda has expanded and deepened; military force and extra-judicial killing have became routine methods of counter-terrorism; and complicity with torturers was normalised. The logic of counter-terrorism was spread to every sphere of public life in Britain as workers in government services were expected via Prevent policy to become the eyes and ears of national security surveillance – not to identify persons where there was a reasonable suspicion of criminal activity but according to a much vaguer category of ideological suspicion – effectively institutionalising Islamophobia in our public services. The definition of the threat was itself transformed: no longer simply a matter of individual acts of violence but a much broader danger, understood in terms of clashes of culture, ideology and values, implicating an entire generation of young Muslims.

Central to the prevailing approach to counter-terrorism is the desire to avoid regular, open criminal trials in front of a jury – because juries can occasionally hold the police and prosecutors to account for abuses. Preferred instead are the use of secret evidence, extradition, citizenship deprivation and restrictions on movement and behaviour that do not require a criminal conviction. Indeed, there have been cases of Muslims deprived of their British citizenship by the Home Office and subsequently extradited to the United States, subjected to rendition or killed by drone. And, despite earlier denials by ministers, British intelligence knew about, suggested, planned, agreed to or paid for others to conduct rendition operations in more than seventy cases in the War on Terror. There is every possibility that this collusion in torture is being, or could be, repeated.

Even on the narrowest measure of success – the reduction of terrorism – the record of UK counter-terrorism over the last twenty years is a poor one. The number of civilian lives lost in ostenisbly fighting terrorism have been many times greater than those that have ever been lost or could have ever been lost due to terrorism itself. Policymakers have not produced a coherent and consistently applied definition of terrorism; nor has the government produced a plausible theory of why terrorism happens. The government’s account of what causes terrorism is remarkably simplistic: that terrorism is caused by the presence of extremist ideology, which is defined as the rejection of British values. This view has been avidly promoted by conservative think-tanks but there is no empirical evidence to support it. It means that policy-making is conducted without any substantial reference to evidence on how policy can actually intervene to reduce violence. And there has been no serious attempt to measure whether particular policies actually reduce terrorism.

Why, then does counter-terrorism policy fail?

All these failures are rooted in a policy process unmoored from any substantial process of democratic accountability. Instead, the aims and means of policy have been set by a security establishment according to its own interests and values. This security establishment has not sought to ground security policy in the problems of political violence that communities in the UK face. And it has repeatedly placed loyalty to elite interests above the need to uphold human rights, especially with respect to Muslim populations, and Tamil and Kurdish communities.

Intelligence agencies, police forces and the military doubled or tripled their counter-terrorism budgets and held onto this funding even as other sectors were ravaged by austerity measures. There are now more than 30,000 people employed directly in intelligence by the British government. But there has been no corresponding level of accountability.

In the War on Terror era, national security policy has increasingly sought to enlist others outside the national security agencies to collaborate in actively producing security. In different ways, local authorities, businesses, schools, universities, hospitals, landlords, media organisations, charities, communities and families have all been allocated active roles, especially through the Prevent policy’s requirement to surveil and challenge extremism. The government’s 2015 counter-extremism strategy, for example, calls for a mobilisation of ‘countless organisations and individuals’ to come together across the UK to ‘fight’ extremism. ‘Local people,’ it adds, ‘have a key role in identifying extremist behaviour and alerting the relevant authorities.’

Yet the one thing ordinary people are not asked to do is to ask the big questions about whether counter-terrorism policy works, if not why not, and what might alternatives look like. This area of policy is deeply authoritarian even as it speaks the language of popular participation.

So what would an alternative look like?

At the heart of our argument is a demand for a genuine democratisation of security policy. Policy-making needs to root itself not in an establishment definition of the national interest but in the actual security needs of ordinary people. Security should be defined not as the absence of risk but as the ‘presence of healthy social and ecological relationships’, as the Ammerdown Group of peace researchers have argued. Rather than transforming our social ties into mechanisms of surveillance, we need to take a holistic view in which we tackle the root social and political causes of violence.

A national audit of security needs, with genuine local community involvement across the UK, should be conducted to provide a comprehensive view of the expressed concerns of ordinary people. This audit of security needs should provide the basis for defining the goals and methods of UK security policy, how resources are to be allocated and the priorities for future publicly-funded research on security.

A much wider process of transparency and accountability will be needed to open up the police and intelligence agencies to democratic scrutiny. Accountability processes need to be spread from the executive and from parliament to the judiciary and the public. An independent commission on the nature and causes of political violence should be established with the involvement of a broad range of academics, other experts and communities.

Within the UK, the regular criminal justice system should be used to bring any charges against individuals accused of terrorism-related offences to jury trial. If there is insufficient evidence to bring a charge, there should be no alternative punishment such as extradition, deportation or restrictions on movement and behaviour that do not require a criminal conviction. There are strong reasons for believing that the steady expansion of counter-terrorism powers has been counter-productive to the goal of reducing political violence. Plots to commit acts of violence within the UK can generally be investigated and prosecuted under regular criminal powers, using normal methods of police investigation, without need for recourse to the terrorism legislation or other special measures. The UK government should recommit to the absolute prohibition of torture and of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.

Prevent policy should be ended. It rests on the flawed official account of what causes terrorism that I mentioned earlier. It collapses mechanisms designed to safeguard children and young people into the structures of counter-terrorism surveillance. Rather than expect social workers and teachers to become surrogate national security investigators, a better approach is to strengthen longstanding safeguarding procedures with the resources needed for effective delivery.The UK should commit to ending involvement in unilateral military interventions. We need a strengthening of efforts to resolve conflicts justly and peacefully.

Finally, we need a judge-led public inquiry to fully investigate Britain’s role in human rights abuses in the War on Terror – in order to ensure the injustices of the past are held to account and structures are put in place to prevent their happening again.

The Labour Party has a particular responsibility to address the harms resulting from counter-terrorism as it was the Labour government led by Tony Blair that incorporated the War on Terror into British policy-making and his successor Gordon Brown who continued and extended the paradigm. Labour’s 2017 manifesto already contained policies that align with our argument and can be built upon, such as the call to review Prevent, to address civil liberties concerns with the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act and to hold public inquiries on past injustices. However, counter-terrorism policy has been one of the least discussed topics within the Labour Party, despite its deep impact on the lives of the over two million Muslims in the UK, and Tamil and Kurdish communities. We hope this report will help to initiate a more vigorous discussion.

Clearly, any government seeking to dismantle any of these counter-terrorism policies will be attacked by its opponents as weak on national security. The temptation will be to not rock the boat and allow counter-terrorism policy to remain unchanged, the better to secure political victories in the core economic policy areas voters are more focused on. We believe this would be a mistake. It would mean a progressive government failing to uphold principles of human rights and racial and religious equality. But as a political strategy, it would also likely be counter-productive. Conceding ground on security policy will not minimise the attacks from right-wing media organisations or politicians, leaving government defending itself reactively and inconsistently within a policy framework not of its own choosing. In this way, a failure to develop a progressive approach to security could end up undermining the credibility of a progressive government’s broader policy agenda. A better strategy, we believe, is to adopt from the outset a coherent, explicitly stated, progressive policy that can be defended consistently and confidently.

A republished speech by Arun Kundnani from the report launch of Leaving the War on Terror: a progressive alternative to counter-terrorism policy (TNI, 2019), at Portcullis House, Westminster, 4 September 2019.