In the fourth of a series, asylum campaigner John Grayson examines the deaths that have occurred of asylum seekers housed in the Direct Provision (DP) system in Ireland.

Sharon Waters of the Irish Refugee Service described the lack of information on deaths and the number of suicides in direct provision accommodation centres as ‘shambolic’ …Waters said many asylum seekers living in the centres go to the refugee service in a ‘very distressed state’ – many self-harming and threatening suicide. ‘The agency takes the approach that it’s not responsible for the people involved, it’s just there to provide them with accommodation and food, but the fact is that these people are highly reliant on RIA [Reception and Integration Agency] and there are a lot of controls on them.’ (Speaking to TheJournal.ie, on 23 August 2013)

While two people are recorded as dying as a result of suicide and one resident was stabbed to death, the “suspected cause of death” of over one third of the people who have died while resident in the direct provision accommodation system is unknown. (Mags Gargan, Irish Catholic, 27 July 2017)

The sheer, breath-taking shoddiness of this is hard to exaggerate. Imagine having a duty of care to those under your roof and not even bothering to ascertain how a third of those who died in your care actually died. What’s really at issue here, of course, is an unwillingness to address whether the abysmal living conditions in Direct Provision affected the causes of deaths of these people. (Donal O’Keeffe, ‘Who cares how asylum seekers die?’ The Avondhu, 1 August 2017)

On 27 July 2017, the Irish Catholic newspaper had a story headed, ‘Cause of one in three deaths in direct provision system is unknown’. The Reception and Integration Agency (RIA) had responded to a Freedom of Information request, on the number of asylum seekers who had died in the Direct Provision (DP) system over the past ten years. The RIA answer revealed that:

‘Forty four people have died in the direct provision system between 2007 and 2017, including three stillborn babies and one “neonatal death”. In fifteen of the cases the Reception and Integration Agency (RIA) record the suspected cause of death as “unknown”, or simply “died”. Among those listed as unknown was a 41-year-old man who was “found in room by roommate” in 2008, a 53-year-old man who was “found dead in his bed at 9am” by his roommate in 2012, a 35-year-old man “found unconscious in room and died in hospital” in 2014, and another man in 2015 “found unconscious in room and died in hospital.”’

In September 2012, Emmanuel Marcel Landa, a Congolese former diplomat, was found dead in the Mosney DP centre. It was suspected that he died as a result of persistent heart trouble. He was 62, and had been in the asylum process for seven years, having arrived in 2005. On 14 July 2011, he was part of a deportation flight to the Democratic Republic of Congo, but this flight was turned back. During this deportation attempt, Mr. Landa suffered a heart attack in Dublin Airport. He suffered two more heart attacks before his death.

Sue Conlan, CEO of the Irish Refugee Council, said ‘The impact of long delays, lengthy residence in Direct Provision accommodation and the real threat of deportation may well have been a contributory factor in Mr. Landa’s untimely death. It is believed that he is the 49th or 50th person to die in the system of Direct Provision since 2000.’

On 16 July 2013, Justice Minister Alan Shatter, answering questions in the Dáil, said:

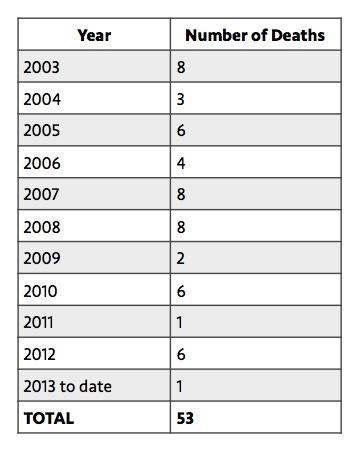

‘The collation of statistics on deaths of asylum seekers living in direct provision commenced in 2002. During the period 2003 to 2013, there have been 53 deaths of asylum seekers who were residing in direct provision accommodation prior to their deaths.

While RIA may have general knowledge of the cause of death, it does not, indeed cannot, hold or have access to death certificates … If the HSE, or a Coroner, were to raise an issue relating to the accommodation in which a deceased person lived prior to their death – this has never happened – then RIA would respond accordingly. It needs to be emphasised that these records are based on informal information and are not official records of death … it is important to say that only one of these deaths can with certainty be said to be a suicide.’

Table one: The number of asylum seekers who died between 2003 and 2013 while being provided with accommodation by RIA in DP centres[1]

The Refugee Integration Agency is not an integration agency

The RIA is part of the Irish Ministry of Justice. It is not an ‘integration agency’. The integration function was given in 2007 to the Integration Unit of the Office of the Minister for Integration, then to the Office for the Promotion of Migrant Integration (OPMI). The OPMI, not the Ministry of Justice, is overseeing the current Irish Syrian refugee resettlement scheme.

The RIA has a precise and very narrow view of its role. According to the RIA Annual Report for 2016, it ‘provides asylum seekers with full board accommodation and co-ordinates certain ancillary services, while their applications for protection are being processed. RIA does not “lease” premises from commercial contractors. Rather it “contracts-in” a comprehensive range of services, which include accommodation, catering, housekeeping, etc., for a fixed period of time.’

In evidence to the 2015 annual review by the Irish Auditor General, the RIA said ‘The State is obliged to make provision for the material needs of asylum seekers while their applications and appeals of decisions are being processed. Direct provision is the means by which the State meets that obligation.’

According to Leonie Kerins, Director of Doras Luimní, an asylum rights NGO, commenting on the Irish Catholic revelations ‘That’s how they see their role, bricks and mortar and the particular needs of asylum seekers are not taken into consideration in terms of separation from family, post-traumatic stress and survival of torture,’ she said.

According to Leonie Kerins, Director of Doras Luimní, an asylum rights NGO, commenting on the Irish Catholic revelations ‘That’s how they see their role, bricks and mortar and the particular needs of asylum seekers are not taken into consideration in terms of separation from family, post-traumatic stress and survival of torture,’ she said.

Finding out the cause of death of people who die in the DP system is also not part of the role of the RIA. In July 2013, the Department of Justice, which oversees the work of the RIA, said that ‘in some cases the RIA will have general knowledge of the suspected cause of death … if information is provided by a centre manager – but it does not “seek information on protection applicants outside its remit”.’

Tahir Mahmood died on 16 September 2013, aged forty-eight. Mahmood lived with his wife and four children in the Towers DP centre, in the Clondalkin suburb of Dublin. His illnesses meant he had difficulties walking, and found it extremely hard to get to the hospital. His requests for a transfer to a more centrally located accommodation centre, and for a hospital social worker, were refused, and he was not given the diet indicated by his liver problems in the centre.

RIA care or coercive rules?

In one of the few cases challenging the DP system[2] in November 2014, a young Ugandan asylum seeker mother, and her three-year-old son, tried to get the Irish High Court to declare that living in a DP regime for four years breached her family and human rights.

The case exposed the coercive and intrusive regime the RIA allowed in its contracts with for-profit providers of DP centres, in this case the Maplestar Ltd hotel company, providing the Eglinton Hotel in Galway with 186 places for asylum seekers. The management had told centre residents that they could expect unannounced inspections and entry to their rooms at any time, that they had to sign in every day; and could not be absent from the centre for periods without giving notice. They could not have visitors in their rooms at any time. The evidence of the RIA to the Court suggested that ‘genuine protection seekers’ should be grateful for the DP system and not protest. Noel Dowling, Principal Officer in the RIA, said:

‘The allegations … demonstrate a startling lack of appreciation for the daily realities of many other non-protection seekers, particularly given the difficult economic circumstances unemployed individuals and low income families currently face … the facilities are designed to be suitable for a genuine protection seeker. It is submitted that were a person genuinely fleeing persecution in their home country, such a person would welcome the quiet and peaceful enjoyment of the Eglinton Hotel on the seafront in Salthill, Galway.’

The Court was scathing about the rules and complaints procedures operated by the RIA (see note 2) but did not rule on the DP system as a whole. The ruling came at the end of a year of protests and hunger strikes, in many DP centres across Ireland, and also major revelations on ‘How direct provision became a profitable business’ from the Irish Times in a series of articles; and an expose of conditions in DP in August 2014 called Lives in Limbo. The government had also been forced to launch the first ever formal investigation into the DP system, under retired judge Dr. Bryan McMahon, which reported in June 2015.

This rate of infant mortality would not be tolerated in wider society

On 22 January 2015 Thejournal.ie reported that:

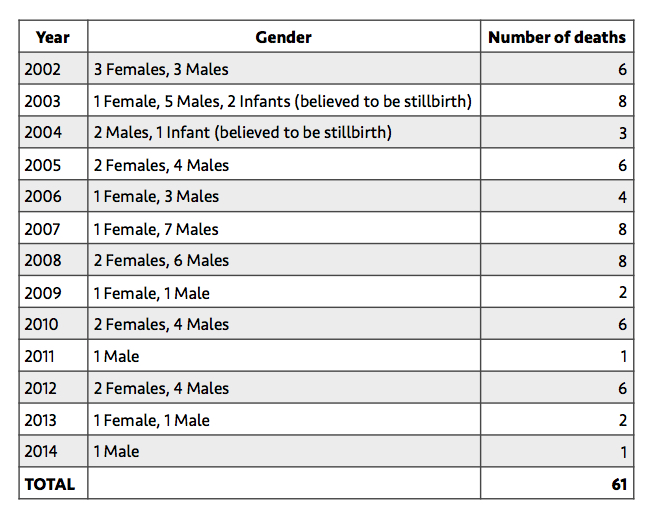

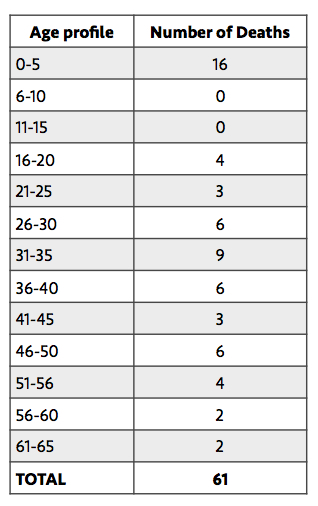

’61 People have died in Direct Provision in Ireland since 2002 – 16 of whom were children aged five and under’

The report was based on figures (see tables below) released in a parliamentary answer by the Minister for Justice and Equality, Frances Fitzgerald. Sinn Féin’s Trevor Ó Clochartaigh, speaking in the Seanad, said: ‘This is a shocking figure.’ He criticised the Department and RIA for their ‘failure to collect and put into the public domain in-depth data in relation to health outcomes for pregnant asylum seekers and their children. We have a responsibility and a duty to ask why children between the ages of 0-5 account for a quarter of all deaths of people living in Direct Provision. This rate of infant mortality would not be tolerated in the wider society and it raises fundamental questions about the suitability of Direct Provision for women and children.’ said Ó Clochartaigh.

Table two: Deaths in DP by gender[3]

Table 3: The ages of those who died in DP

The Institute of Race Relations, in March 2015, published Unwanted, Unnoticed, a report documenting one hundred and sixty asylum and immigration-related deaths within EU member states, in the five years to December 2014. For Ireland, the report identified seventeen deaths directly linked to the Irish asylum system – only two of these deceased people could be identified: Emmanuel Marcel Landa who died in Mosney DP centre and Tahir Mahmood who died whilst resident in Clondalkin Towers DP.

In April 2015 conditions in the Clondalkin Towers DP centre were highlighted by a motion to Dublin City Council from Councillor Francis Timmons (Ind), to ‘highlight the poor conditions in direct provision centres across Ireland and also to call for a full report on the quality of life within the Towers.’ The Dublin Gazette spoke to an African man resident in Clondalkin Towers, who had been in the DP system for eight years. ‘Living here is like an open prison … I’m still in limbo and I don’t know why this process is taking so long … I’ve tried to commit suicide on two occasions, because of the effects that direct provision is having on my mental health.’

A suicide in Kinsale Road DP centre in Cork

On 23 August 2016, a 36-year-old woman from Seoul in South Korea took her own life in her room in the Kinsale Road DP centre, outside Cork city. She had been at the centre, run by the Aramark Food Corporation, with her six-year-old son, for fifteen months.

The inquest in January 2017, was told that she had spent three months in Balseskin DP centre near Dublin, after her arrival in May 2015, longer than usual because of her medical condition. The woman, and her (then) five-year-old son, were sent to Atlas House DP centre in Killarney, County Kerry, around 200 miles from Dublin. RIA principal officer Eugene Banks told the coroner that she was then ‘transferred, a short time later, to the Kinsale Road facility, where she would be closer to certain acute and support services.’

The day after the death was announced, Lucky Khambule of MASI, who had himself been a resident at the Kinsale Road centre, met people at the centre. He said ‘She had been here for about a year. She had on occasions been to the doctor and she was evidently a quiet, sad person. The residents have decided they will hold a procession with flowers and candles, and lay them at the block where she lived.’

The day after the death was announced, Lucky Khambule of MASI, who had himself been a resident at the Kinsale Road centre, met people at the centre. He said ‘She had been here for about a year. She had on occasions been to the doctor and she was evidently a quiet, sad person. The residents have decided they will hold a procession with flowers and candles, and lay them at the block where she lived.’

Local politicians in Cork alleged that the DP system was to blame. The Green Party’s representative for Cork North Central, Oliver Moran, described DP as like ‘modern-day concentration camps … this death was preventable and this is a result of conscious policy decisions over time. We’re reiterating our call to end direct provision. Now isn’t the time for wringing hands.’

The Green Party representative for Cork South Central, Lorna Bogue, said ‘the State needs to accept responsibility for the death of a young mother in its care.’ Councillor Bogue told local media that ‘she believes the woman took her own life due to the conditions she was living in, and she’s calling on the State to step in and ensure her son’s citizenship application is fast tracked.’

On 6 September 2016, the Kinsale Road Accommodation Centre Action Committee staged a protest of around fifty residents, on the Grand Parade in Cork city centre, ‘to highlight their plight and that of some 250 other residents at the centre where a Korean asylum seeker took her own life’.

The Irish Times reported committee secretary Asad Mahmud saying, ‘The tragedy has affected all of us in different ways – the women are scared, the children are scared, and are reacting in this way by raising their voices in protest, so that the authorities will do something about it. We think this lengthy asylum procedure triggered this woman’s death, because the way her application was handled by the system made it worse for her,’ said Mr Mahmud, who said the group was also seeking an end to deportations.

Business as usual for deaths (and births) in the DP system?

The revelations from the Irish Catholic investigation into deaths in DP in July 2017 added little new to the image of a callous and uncaring RIA but there was still anger in the media.

Journalist Donal O’Keeffe commented that ‘these were de facto deaths in State custody … What stood out most for me was the 16-year-old asylum-seeker recorded simply as “sudden, died in school”. The sheer, breath-taking shoddiness of this is hard to exaggerate. Imagine having a duty of care to those under your roof and not even bothering to ascertain how a third of those who died in your care actually died. What’s really at issue here, of course, is an unwillingness to address whether the abysmal living conditions in Direct Provision affected the causes of deaths of these people.’

The Irish Catholic article was part of a political culture in Ireland, early in 2017, which was full of protest and anger following the introduction of the International Protection Act (IPA) in December 2016, and an increase in deportations (see links below to my earlier articles on the DP system in Ireland). MASI, Anti Deportation Ireland, and United Against Racism organised an information and training programme across the DP centres to steer asylum seekers through the new paperwork for the IPA. Lucky Khambule of MASI, and Memet Uludağ of United Against Racism, worked with People Before Profit Alliance TDs to gather the signatures of thirty-seven deputies to force a debate in the Dáil on DP; this took place on 30 March 2017.

The debate showed a general view across the deputies present that DP, in the words of Eoin Ó Broin of Sinn Fein:

‘It is not a badly managed system. It is not a system that needs some tweaks and changes. It is a scandal. It is about time every politician in the House declared it a scandal and said it has to end. Then the conversation will change. It is not just about removing the rough edges.’

There was a call from Róisín Shortall of the Social Democrats that:

‘What is required urgently is Government action, not more words. Direct Provision was only ever intended to be a short-term response, but it has since become a national disgrace. There is no disagreement with that assessment … We all want the Government to act, as the quality of life of those currently living in direct provision will not be improved by us making statements about the system’s flaws. We need political action.’

There was also a reminder in the debate of why the deputies wanted the end of Direct Provision. Mattie McGrath, the Independent deputy for Tipperary, spoke particularly to the issue of children. He said:

‘Talk is easy and talk is cheap. It is appalling to read reports that some children spend almost their entire childhood in these centres … It is incarceration, nothing less. Prisoners are treated better. This must end.’

The deputy had submitted a parliamentary question, ‘seeking the number of children who have been born to those in the direct provision system since its introduction in 2000. I received a reply from the Minister of State, Deputy Stanton, that the information I had requested is not readily available, as it is not collated, by either the Department of Justice and Equality or the Registrar General of births, marriages and deaths. That is outrageous …. it is outrageous that we cannot tell the number of newborns in the centres. It is scandalous. It is extraordinary when one thinks about it. Presumably those children born to those in the asylum process are de facto part of that process, yet we have no data or numbers available.’

Five years ago, in 2012, Liam Thornton, commenting on the Irish Refugee Council’s report on children in Direct Provision centres, State Sanctioned Child Poverty and Exclusion, argued:

In Ireland, the one thing we do well is developing punitive regimes to punish children … There is an obsession with containment of those who we, as a society, find problematic or difficult to deal with. Children of asylum seekers are one such category. We dislike their difference, their otherness, their presence in this country. Not necessarily the children, but their parents … So, we allow little children to grow up in centers, where they never see their mothers or fathers cook, or clean, or work. We, as a society, allow these children to wallow in an existence for years of set eating times, living with strangers, sharing rooms with other families or individuals … And we, in Ireland, do nothing. We as a society could not give a damn.

Apparently neither deaths, nor births, in the DP system, are of much concern to the Irish State.

Related links

IRR News: The companies who profit from the Direct Provision system

IRR News: Making profits in Ireland’s asylum market

IRR News: Direct Provision in Ireland: the holding pen for asylum seekers

IRR News: Daisy and the £4 billion asylum housing contracts

IRR News: ‘I killed three … maybe four rats in my kitchen this summer’

Bringing out facts is a great job and I am sure you have the courage to do that. Your efforts in this regards and fighting for the rights of asylum- seekers are highly adorable. Not only you, all those working in hand to hand with you deserve great recognition and thank you for their unstoppable input.

You people are indeed true ambassadors of Britain, acting as front-line squad to project and defend the actual values of the country in the eyes of others.

Well-done! keep it up.

Regards Thanks