The assault on the family life of migrants inevitably leads to the creation of ‘immigration offenders’, to detention and deportation.

The month-long detention and deportation to Singapore of a grandmother with a 27-year marriage to a British husband, British children and a British grandchild rightly caused outrage. Yet it is no aberration, but an inevitable outcome of the assault on family migration by the Tories, from 2010 on.

As home secretary, Theresa May was tasked with implementing David Cameron’s pledge to reduce migration from its annual average of nearly a quarter of a million to the ‘tens of thousands’. In fact, net migration rose to 330,000 during her time in the post. But she certainly tried hard, introducing a cap on work permits and on student migration, and coming down particularly hard on family migration. The rules setting out the criteria for British and settled residents to bring non-EU family members in were made extremely tough.

The assault on family migration

A month after the coalition’s victory, in June 2010, she announced that from November that year, most non-EU spouses and partners coming from a non-English speaking country would need to pass an English-language test before joining British or UK-based residents in the UK. There were exceptions for those with a degree taught in English, over 65s and those with a mental or physical condition or ‘exceptional compassionate circumstances’ preventing them from taking the test, but Home Office guidance said that illiteracy or financial difficulty could not count for these purposes.

New Labour had introduced the language and life in the UK test in 2007, to be taken at the point a temporary migrant sought permanent resident status, or ‘indefinite leave to remain’. For spouses and partners, this was at the end of the two-year probationary period designed to test the genuineness and durability of the relationship. The introduction of a pre-arrival language test was sold as necessary to enable new migrants to integrate, but was in reality designed to cut numbers – which it did.

A test case challenging the rule was brought by the wives of a Yemeni with no formal education, illiterate and unfamiliar with the Roman alphabet, and of a rural Pakistani Urdu speaker for whom the language course would involve a four-hour daily round trip for a period of months or relocation in a city, which he could not afford. Neither man could learn the language before arrival – so the British-born child of the Pakistani was without a father, and the British wife of the Yemeni was forced to live away from her family and friends to be with her husband. In 2015, the Supreme Court upheld the rule, but held the guidance on ‘exceptional circumstances’ too rigid.

The language test, though, was just the starter. In July 2012, a new raft of requirements was brought in, in a complete overhaul of rules for non-EU family migration. The probationary period for spouses and partners was increased from two to five years, so relationship breakdown within five years meant the non-EU partner having to leave the country, unless there was proof of domestic violence. It was the minimum income requirement which proved the most controversial. Since the 1970s, incoming family members had to be housed and supported ‘without recourse to public funds’. But the new rule meant that British-based sponsors would need a minimum gross income of £18,600 to bring in a partner (£22,400 for a partner and child, and an extra £2,400 for each additional child). Alternatively, they had to have substantial savings (at least £16,000 plus two-and-a-half times the shortfall in the sponsor’s earnings). The level set for the minimum income was, according to Baroness Warsi, who fought against it in Cabinet, far short of the £40,000 urged by Theresa May, but was still above average earnings for 301 of the 422 occupations listed in the Office for National Statistics’ Statistical Bulletin: Average survey of hours and earnings for 2015, particularly for those living outside London – and a long way above the minimum wage, which worked out at £13,400. Home Office guidance stipulated that the money had to be the sponsor’s own earnings, with no account taken of the earning power of the incoming partner, or support from third parties. It was estimated that the new provision, explicitly introduced to cut numbers, would reduce family visas by around forty-five per cent.

A test case brought to challenge the rule revealed its impact, and its inhumanity. MM, a Lebanese refugee, earned around £15,600 as a quality inspector. His graduate wife was a qualified pharmacist and a fluent English speaker, with good potential earning power in the UK, and his family had undertaken to support the couple for as long as necessary – but the refusal of her visa took only MM’s earnings into account. AM, a British Pakistani who had lived in the UK since 1972 and had been married since 1991, was looking after four of his five children in the UK and could not work. Another litigant, SJ, a British Pakistani with no qualifications and a history of low-paid employment, was married to a civil servant, and argued that the rule discriminated against women, particularly British Asian women, who suffer from low rates of pay and employment. The fourth litigant, NT, a refugee from the DRC who became naturalised British, had married a DRC citizen but could not live there, so his low earnings meant the couple could not live together anywhere. His wife had had a miscarriage after her visa was refused. In February 2017 the Supreme Court upheld the rule, and the principle of a minimum income requirement, as lawful, but ruled that the interests of children needed express consideration, and that guidance which told officials to ignore partners’ earnings and support from others was too rigid.

It was not just spouses and partners who were hit by the overhauled rules. The criteria for admission of other relatives – parents and grandparents, adult children and adult siblings – were made impossibly tough. Under the new rules, a parent or grandparent seeking entry ‘must not be in a subsisting relationship with a partner’ who is not the child’s other parent or grandparent. A widowed mother can no longer be admitted on proof of her dependency on her British-based son or daughter, and of her lack of close relatives in her home country. She, and any other ‘adult dependent relatives’ now additionally have to show that ‘as a result of age, illness or disability’ they ‘require long-term personal care to perform everyday tasks’ and ’must be unable, even with the practical and financial help of the sponsor, to obtain the required level of care in the country where they are living, either because it is not available and there is no person in that country who can reasonably provide it; or it is not affordable’. This is almost camel-through-the-eye-of-a-needle territory. The message to loving or dutiful children with parents abroad is: go and look after them there, don’t bring them here.

An ignoble history

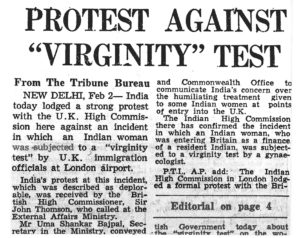

It has never been easy for non-EU family members, particularly from the Indian subcontinent, Africa and the Caribbean, to join British citizens and UK-settled migrants settled in the country. Women from the Indian subcontinent seeking entry to join husbands in the 1970s faced queues at the British High Commission of over two years just to get an interview – and the delays for spouse visas then led to the degrading virginity tests at Heathrow for those coming as fiancées, to check that they were not already-married queue-jumpers. Children applying to join parents were subjected to bone-age X-ray checks, as unreliable as they were dangerous, until an official inquiry ended their use in 1981. Children from the Caribbean seeking to join mothers who had migrated to the UK, leaving the children with grandparents, were refused because mothers could not prove that they had ‘sole responsibility’ for the child. All family members were questioned exhaustively about the layout and details of their home, answers compared, discrepancies counted and applications refused as ‘not related as claimed’. In the 1980s and 1990s between half and two-thirds of all husbands from the Indian subcontinent were refused entry to join British-based wives because they had not satisfied the entry clearance officer that the primary purpose of the marriage was not immigration.

Although the New Labour government abolished the primary purpose rule in 1997, and also made it possible for same-sex partners to come to the UK (prompting former Tory Home Office minister Anne Widdecombe MP to worry that there would be ‘no real means of testing’ these relationships), it brought in new restrictions. The minimum age for entry of spouses and partners was raised from 16 to 18 (a minimum age of 21 was rebuffed by the precursor of the Supreme Court, the House of Lords Appellate Committee). It also brought in a measure requiring foreigners to obtain Home Office permission if they wanted to marry in the UK other than in the Anglican church – a law which was struck down by the Supreme Court.

Ironically, on both occasions the court used New Labour’s crowning achievement, the Human Rights Act, incorporating the European Convention of Human Rights into UK domestic law, to overrule the government, relying on provisions protecting respect for family life and the right to marry and found a family, and prohibiting discrimination. The Act does not give absolute rights (except the right to be free from torture or inhuman or degrading treatment), but it does require government interference with rights such as family life or freedom of speech to be justified by legitimate aims, and proportionate to those aims. Since the introduction of the Act in 2000, its protection for family life has mitigated the harshness of the rules on family migration – and has on occasion prevented the removal of offenders.

The Human Rights Act: May’s bete noire

It is this which has drawn the ire of Theresa May, no passionate believer in human rights, at least not for the undeserving or for foreigners. As home secretary, she and the Daily Mail enjoyed a symbiotic relationship, each feeding the other’s outrage at each successful use of human rights law by undeserving foreigners to avoid their just deserts of deportation. While the Mail campaigned against immigration judges who allowed the appeals of foreign offenders citing the right to respect for their family life (and the Telegraph ‘named and shamed’ them), May conjured tales of cats preventing deportation, and devised ever more restrictive rules.

May’s Home Office introduced measures like Operation Valken, the vans touring the streets with the message ‘Go Home or Face Arrest’ (withdrawn after an outcry); the ‘hostile environment’ to force irregular migrants to deport themselves, a package of measures including the ‘right to rent’, which requires private landlords to check the immigration status of all occupants of their premises, on pain of prison; the NHS surcharge for migrants; the use of NHS and school records to trace overstayers. And ‘Deport first, appeal later’, introduced in 2014 to tackle the mythical abuse of serial appeals by foreign criminals to prevent or delay their deportation. The only appeals left standing by the Act were those where asylum or human rights were in issue, and appeals arguing that human rights would be violated by deportation would be heard after the deportation unless ‘serious and irreversible harm’ would be caused. In 2016, ‘deport first, appeal later’ was extended from foreign criminals to everyone facing removal.

May’s Home Office introduced measures like Operation Valken, the vans touring the streets with the message ‘Go Home or Face Arrest’ (withdrawn after an outcry); the ‘hostile environment’ to force irregular migrants to deport themselves, a package of measures including the ‘right to rent’, which requires private landlords to check the immigration status of all occupants of their premises, on pain of prison; the NHS surcharge for migrants; the use of NHS and school records to trace overstayers. And ‘Deport first, appeal later’, introduced in 2014 to tackle the mythical abuse of serial appeals by foreign criminals to prevent or delay their deportation. The only appeals left standing by the Act were those where asylum or human rights were in issue, and appeals arguing that human rights would be violated by deportation would be heard after the deportation unless ‘serious and irreversible harm’ would be caused. In 2016, ‘deport first, appeal later’ was extended from foreign criminals to everyone facing removal.

The underlying attitude behind both the restrictions on family migration and the crackdowns on overstayers and refused asylum seekers who don’t go home is one I first encountered as a young barrister representing the family of an asylum seeker who had hanged himself in Harmondsworth immigration detention centre in the early 1980s. The coroner objected to my point that these places, unlike prisons, had no suicide prevention strategy, saying ‘But this isn’t a prison! Here, they are free to go!’ It bespeaks an utter failure of imagination, a failure to comprehend anything of the messy realities of migration and family life. Thus, instructions to officials remind them that ‘The fact that refusal may … result in the continued separation of family members does not of itself constitute exceptional circumstances where the family have chosen to separate themselves’. This turn of phrase was echoed by May’s immigration minister Robert Goodwill, in his February 2017 explanation for capping the admission of lone refugee children from Europe at 350: ‘In the majority of cases, these are not orphaned children but children whose parents are sending them on a hazardous journey’ (my emphasis). You can hear the note of complacent condemnation in these phrases. What sort of families, it sneers, choose to separate themselves, what sort of parents send a child off on a hazardous journey? Why do they deserve help, sympathy, special treatment?

Becoming an immigration offender

It was this failure of imagination on the part of the Home Office that led to Mrs Clennell becoming an overstayer. She came to the UK in 1988 and after marrying her British husband two years later, was granted indefinite leave to remain – permanent resident status. It was her wish to look after her ageing and ill parents in Singapore which led to her losing that status, by remaining out of the UK for over two years. The ‘returning resident’ rules allow permanent residents to be out of the UK for up to two years – but after that, the status is lost, although border officials may allow re-entry to someone who ‘has, for example, spent most of his life here’. Evidently, neither the length of Mrs Clennell’s marriage, her children and grandchild, nor the entirely selfless reason for her absence from the country, were compelling enough reasons for her to be readmitted to resident status. She was instead granted a visitor visa, which required her to leave the country after six months and obtain a new visa from abroad. After her husband underwent surgery, she overstayed her visa to be able to continue to care for him.

Thus it was that in January, border officials came to the couple’s Chester-le-Street home and arrested her, taking her to an immigration detention centre where she spent a month before spending the night of 25 February at the notorious Dungavel centre in Scotland, and being put on a flight to Singapore the following day. She described how she was made to feel like a terrorist, escorted by guards who held her arms and were posted on the door when she went to the toilet, as according to the Home Office, she posed a threat of violence.

EU citizens next?

Since Mrs Clennell’s deportation, £55,000 has been raised by crowdfunding for an appeal against her removal. Meanwhile, the Daily Mail prime minister May is sitting on her hands as EU nationals and their family members in the UK become increasingly worried about their future. They have never faced the kinds of restrictions non-EU nationals have faced: EU law recognises that free movement must include family, and not just partners and children but parents, grandparents and grandchildren. Now, though, many long-term residents, particularly those who are or have been at some point ‘economically unproductive’, are being told, just as they seek the security of permanent residence (filling in an 85-page form to do so), that they don’t qualify as they remained out of the country for too long, or never took out ‘comprehensive sickness insurance’ (CSI). These are requirements they have never been made aware of before, and the demand for private health insurance is, according to the European Commission, in breach of EU law. (The Commission says that the NHS, which is freely available to all EU nationals, satisfies the CSI requirement.) Although the notices telling EU nationals without CSI to leave the country are said to have been sent in error, it feels rather like a practice run for 2019, with Home Office officials just jumping the gun a little.

The Daily Mail has supported Irene Clennell’s campaign to return – which is somewhat ironic, since it is Mail–driven policies that have caused her deportation. Will the Mail also campaign for the many families separated by language and minimum income tests, or for the EU nationals without CSI, given the paper’s strident denunciation of ‘health tourists’ and ‘benefit tourists’?

Related links

Read about Frances Webber’s Borderline Justice

What about the demonization of the white working class?